A profound quiet

IN a recent article describing the carefree, spring-is-here attitude many Americans begin to display this time of year, Time magazine inquired of a Boston pollster what issues really worry people these days. "Nothing much," he replied. In this "time of great prosperity," the article continued, "there are problems and discontents, but in April they somehow seem soluble."

The present generation of college students, while not exactly giving the impression that it is living in an eternal spring, seems to have impressed the media that it isn't worried about much, either - at least, much outside its own pond. "A self-motivated, self-improving lot," proclaimed Life in its Special Report on Youth last fall. "[For students] the seventies are a time of retrenchment, of taking stock of what they have and getting back to basics." Basics like "getting a good job after graduation," which eight out of ten college newspaper editors told Gallery magazine in 1976 was the most pressing issue on their campuses.

While no one knocks concern for one's future as a legitimately worrisome issue, students of the seventies have at times been accused of being too introspective, not aware or concerned enough about national and international issues. And even though student activism has had a sort of epiphany of late, with the series of protests in mid-April at Dartmouth, Princeton, Brown, and Wesleyan against university investment in companies doing business in South Africa, an observer would be hard-pressed to mistake this generation for the hell-no-we-won't-go students of the sixties. As one professor remarked while watching a 25- Person anti-South African investments rally in front of Parkhurst Hall last month, "Compared to the takeover [of Parkhurst to protest the presence of ROTC on campus in 1969], this is definitely J. V. stuff."

But just because today's students are less vocal or visible in their concern for political issues, does this mean they are less concerned? Some observers, like Professor of Mathematics John Lamperti, would say so, citing "creeping pre-professionalism" and an ever-tightening job market as robbing the campus of much of its intellectual and political life. Others, like Professor of English Jeffrey Hart, claim that students of the seventies are no more or no less concerned than their forebears of ten years ago - that minus the chanting, striking minority, there is very little difference between the values of one set of students and the values of another. Still others, like John McGrath '78, recognize a "latent" or "dormant" political consciousness that awaits graduation and departure from the Hanover Plain before conversion into action.

What is the political state of students at Dartmouth in 1978 - nine years after the taking of Parkhurst, two years since the reinstatement of ROTC, and with seniors undeniably affected by the nationwide job crunch? Does the College give the student a chance to be an informed, thinking political animal? And, if so, does the student seize the chance?

THE means to political insight are available, but that doesn't prove students take the time to obtain it. Newspapers rank low on the list of ways to keep informed. "Let's face it," says Jay French '79, a member of the Young Democrats at Dartmouth, "in daily life here there's less motivation to keep up with current events than there is to keep up with chapter 7 of the history text." Other students emphasize the need for easy access to information, which for most mean television and radio news broadcasts. "It's just too much to read a New York Times every day," says Barbara Snyder '78. "The College encourages you to do well in your courses and get involved in other things. A half-hour with Walter [Cronkite] is a good, fast way to get informed, and it's about all an average student can spare."

While acknowledging that they feel more of their fellows ought to make time to read a daily newspaper, some students blame the College's location as a negative incentive to keeping current. "If we were in someplace like New York City, it would be hard to avoid news," says Laurie Woods 'BO of the Young Democrats. "But here everything seems so removed from what's going on." John McGrath agrees, adding that, because of the College's advantageous location for sports and outdoor activities, "there is so much encouragement to be out in the fresh air, so much less to be inside poring over a newspaper." The encouragement may not be entirely institutional, as French notes: "When people are here [in Hanover], they tend to enjoy their seclusion. They get away from Hanover to get informed and involved." His assertion is at least partially borne out by students' comments that, when they go home for vacations, they almost automatically begin reading a daily newspaper and watching television news more regularly.

If the College's location serves as a deterrent, conscious or subconscious, to keeping up with the world, the College's calendar helps make up for it. The Dartmouth Plan's adaptability allows students to get away from campus at unconventional times - a chance which many students (75 per cent, at last Dartmouth Plan Office tabulation) put to use through College-sanctioned foreign study or domestic programs. The Government Department alone sponsors two such programs - a spring work-study term in Washington and a fall independent study term in Rumania - which have been "terribly helpful" in increasing student awareness of foreign and domestic policy issues, says Laurence Radway, head of the Government Department. But "any program that gets students out into the world helps achieve this goal," he adds; in Radway's introductory course on international politics this fall (Government 7), eight students wanted to write final papers on the U.S.-Great Britain-France battle over the Concorde's landing rights because "their French host families on LSA [Language Study Abroad] had badgered them about it the term before. Otherwise, they probably wouldn't have known about it, or cared."

Students also avail themselves of numerous internship programs which help place them in areas of public service; some, like the recently introduced Policy Studies Internships, were "300 per cent oversubscribed the day after they were announced," according to the chairman, Professor Frank Smallwood '51. Many, however, like junior government major Eleanor Shannon, still feel that "the best way to learn is to do it yourself." Shannon, current chairman of the student-run World Affairs Council at the College, interned in the Virginia State House and believes, "I could never have done as much on a Dartmouth program." Alan Wohlstetter '78, past World Affairs Council president, agrees; his initiative led to a six-month association with the Udall presidential campaign in 1976. "A Dartmouth program, even one offered through an internship placement service, is too institutionalized," he says. "The College gives you the chance to be informed by offering off-terms, but you pretty much have to carry the ball yourself to get anything worthwhile out of them." But how many students do "carry the ball?" "Unfortunately," says Radway, "too few students are self-starters. The ones that are, are precious resources. Thank goodness they come back to campus to talk about their experiences."

Not only students, but faculty, scholars, and experts in political science and policy issues speak at the College in an effort to "surmount the obstacle of location," according to Jeffrey Hart. In 1970 Hart, an editor of the National Review and a nationally syndicated columnist, founded the Dartmouth Committee for Intellectual Alternatives (DCIA), one of the several organizations now in existence primarily to sponsor speakers and to encourage political debate. While the DCIA and its parallel group, the American Forum, are conservative in political leaning, programs offered by the Young Democrats, College Republicans, World Affairs Council, Libertarian Alliance, and Dartmouth Radical Union even out the range of views presented on campus: from William F. Buckley, Jr. to Daniel Ellsberg, Ernst Van Den Haag to Betty Friedan (whose confrontation at a symposium last spirng, when Friedan stalked off the podium after a Van Den Haag aside about feminism being the result of too much testosterone, is by now local legend). Even if speakers of lesser prominence don't reach the 300-plus audiences an Ellsberg or a McGeorge Bundy draws, sponsors like the World Affairs Council are often pleased with a crowd of 40 or so. "For some speakers we couldn't wish for more," says Wohlstetter. "There's a place for intimate discussion just as there's a place for the circus atmosphere of a big speaker." And some forums, such as the recently held New England Student Conference on Arms Control and Disarmament and the now-annual Senior Symposium, provide both.

POLITICAL interest groups at the College exist as more than mere sources of funds for speakers. Their main purpose, according to members, is the discussion and dissemination of political information. Most, like the World Affairs Council and the three so-called "partisan groups" (the Young Democrats, College Republicans, and Libertarian Alliance), were formed by students wishing to indulge academic curiosities about issues they had only touched upon in class. Meetings usually consist of little more than bull sessions over lunch or dinner once a week, occasionally with assigned readings or with a faculty guest. And, as might be expected, the groups draw a hard core of government majors, foreign-policy enthusiasts, and veterans of leave-term internships in the public sector. The combined active membership of the five most established groups - the World Affairs Council, the Radical Union, and the three partisan groups - totals less than 150.

What the political interest groups (withthe exception of the Radical Union, or the small, issue-based coalitions which resulted from its breakup in 1975) do not exist for is political action or party work - activities which, many members feel, might chase away potential members. The two conventional partisan groups are especially hardhit. Reconvened during the 1976 presidential elections after a stagnant period in the early seventies during which "nobody even looked in the mailbox for two years," according to Jay French, today the Young Democrats and College Republicans together number only about 15 solid members - none of whom, ironically, considers himself or herself a tried-and-true party supporter. "We're in this because our leanings just let us feel at home with the general philosophy of the party," says Young Democrats president Herb Lingl '80. "Ties with the party are good for the information and contacts they can provide, especially in an election year. But otherwise, I think there's room for the Young Democrats to be a sort of umbrella group, a forum for liberal information and discussion." College Republican Tom Bell '78 has a similar view of his group. "It's not that we all wanted to be Republicans when we formed the group. We wanted the College Republicans to be us."

If this is so, why so much non-partisan sentiment? "Students tend to shy away from party labels," Steve Manacek '79 of the College Republicans feels. "Not only are they wary of being 'branded' when there's no need to be, they just aren't interested in the kinds of things party affiliation has to offer, like involvement in local politics." And sure enough, contrary to the main emphasis of youth party groups at larger state universities, Dartmouth's partisan groups tend to avoid local politics and conventional party work like ringing doorbells and distributing campaign literature. "First of all, it's hard to mobilize students from all over the country to work on New Hampshire elections," Jay French says. "And secondly, college students, and Dartmouth students in particular, just don't have the time for that kind of thing while they're enrolled. If they want to become active, they do so in an offterm." (At least two students, Mark Connolly '79 and Mike Hanson '77, have been able to balance studies and an active political life. See box.) Besides, adds Fritz Rohlfing '78, president of the Libertarian Alliance, "I don't think the purpose of a party group necessarily has to be doing party work. Our membership list is on file with the national, and if they want to solicit help directly, fine. What we do in terms of discussion and education is more important for right now."

No such non-activist feeling exists among the members of the Upper Valley Committee for a Free Southern Africa, or the Upper Valley Energy Coalition, or any of the other Radical Union spinoffs. The Radical Union, formed from the anti- ROTC protests at the College during 1974-75, decided it would "from time to time take up other causes," according to former adviser John Lamperti. Lately those causes have included South Africa's apartheid policies, the spread of nuclear power, and the question of race and sex discrimination in higher education. Meetings often take the form of planning sessions for future rallies, petition drives, and other actions. "I find it encouraging the number of students who still care enough to question the system and do something about it," Lamperti says. "I find discouraging the number that don't." Unquestionably, activist groups such as these are in the minority among politically minded people at the College; the Radical Union's membership stands today at about 20. Former Radical Union member Blaine McBurney '79 finds the student body "terribly uninformed and apathetic. One senior I talked to actually didn't even know what 'apartheid' was." "It was really nice, that sixties mood of awareness and questioning," Lamperti says. "I don't regret so much students' lack of involvement in political parties, but that concern for the really big issues that seemed to come with the anti-war protests. I miss it."

NOT many of Lamperti's colleagues join him in wishing back the militant sixties. Many of them, in fact, are more laudatory of student awareness and involvement than the students themselves. Associate Professor of Government Don McNemar, whose specialty is international relations, sees the "more introspective mood of the past several years" as "a boon to interest in foreign affairs and policy issues. Students see a more interdependent world and are interested in taking critical perspective on it - but from the inside." McNemar's colleague Laurence Radway sees the same concern for policy issues over political issues on the domestic side. "I've found students have a lively interest in public affairs," he says. "Their issueorientation encourages them to pick up a variety of 'good causes,' those which seize their moral imagination." Even in an economics course such as an antitrust seminar, student political awareness was "very keen," says the professor, Don Basch.

If professors are concerned, however, it is that discussion could be more informed and sophisticated, both inside and outside class. Hart sees the problem as one of "not reading the same books and journals; if you read the same books, you can at least talk about them." Radway sees part of the problem as "the absence of young graduate students in the discursive disciplines [social sciences and humanities] who keep scholarly debate going and encourage it of undergraduates." Professor of Economics Martin Segal blames in part "student laziness. They come here for the most part with their political minds made up and they look to have their opinions reinforced. Certainly they are exposed to new ideas, and many are very receptive to knowledge. But it's the rare student who will sit down and really debate you." "What it really comes down to," claims Radway, "is just a pitiful lack of information on students' parts. If it's not in their area of concentration or related to their career plans, students seldom take the time to get that information." And, in fact, a poll conducted in the summer of 1976 by two of Radway's students confirms this lack of information; while 75 per cent of the students surveyed showed concern for international policy issues, fewer than 30 per cent could name the prime minister of Israel.

To combat this, some professors use the classroom as a workshop in policy-making and rudimentary politicking. Associate Professor Dana Meadows' classes in environmental policy-making prepare as a class project recommendatory briefs on issues of environmental policy and forward them to lobbyists in Washington. Radway, a former state Democratic chairman who himself ran for U.S. Senator in 1974 (he lost in the primaries), routinely invites local politicians to lead discussions in his classes. Not even Hart's English courses leave the political stone unturned. He tries to coordinate parts of his syllabus with whatever the DCIA or American Forum will be presenting in a given term (for example, this spring two conservative journalists will debate pornography; Hart's "Age of Johnson" students are reading Fanny Hill). And many professors, including McNemar, Basch, Segal, Radway, and Policy Studies Program Chairman Smallwood, require the reading of a daily newspaper for certain courses. But Segal says, "I understand completely the crunch students feel. Their priority is course-work. Hopefully, that will include more than reading a textbook and listening to a lecture, but sometimes that is all students have the time or inclination to do."

Students, too, feel the same crunch professors complain about while trying to present a large quantity of academic material in a ten-week term. "For all the flexibility and convenience of the Dartmouth Plan," says Steve Manacek, "it has created a monster in the shortness of the term. If a student and professor, or a group of students, want to discuss a point raised in class, they generally have to do it extracurricularly." It was precisely to handle this overflow discussion that some of the political interest groups were formed. In addition, McNemar says, "I recommend to interested students internships, special or honors projects, or independent study courses." Anything but going into higher education. "That," he adds, "is a preprofessional crunch like nothing else."

WHAT begins to emerge, then, is the following picture: students who have all the tools and resources they need to become informed, involved political animals, save two: time and immediate incentive. With very few students involved in local politics, and with national and international politics physically - and in some cases, spiritually - removed from campus, many students have simply put their political activity on "hold." The general feeling prevails, according to Jay French, that "the college years are for Camp Dartmouth, for hiking in the woods, for skiing, for Winter Carnival - and, in between, for gathering the information and getting the grades necessary to be able to do something once you're out." Most would agree with John McGrath that "Dartmouth is not apolitical or anti-political, but merely politically dormant."

"In some ways it's a pity," says Alan Wohlstetter. "I know the on-campus debate suffers some because students view politics as something for 'out there.' But in the end, it's probably better. We deserve a respite before we all go out and change the world."

The South Africa issue has brought out a dedicated band of demonstrators. Yet thescale of student support left one sympathizer not knowing whether to laugh or cry.

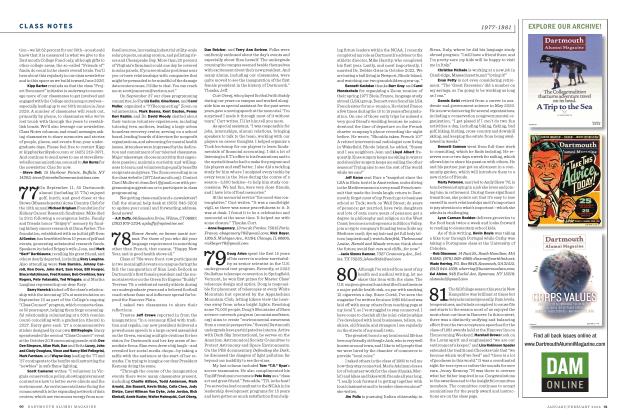

Legislators Mark Connolly (left) and Mike Hanson in the New Hampshire State House "a very easy place to get lost in.

Anne Bagamery '78 is an undergraduateeditor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

May 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

FeatureCastles in the Clouds

May 1978 By George Hathorn -

Feature

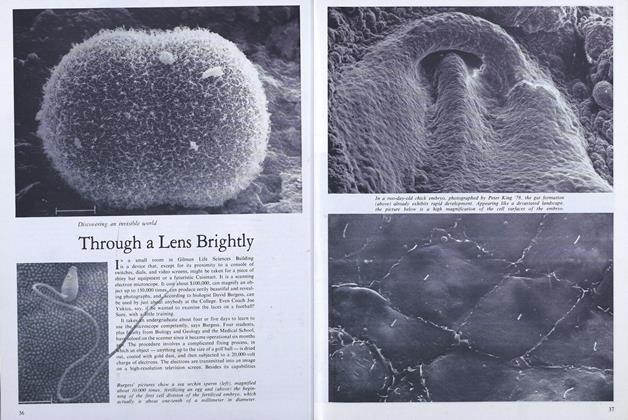

FeatureThrough a Lens Brightly

May 1978 -

Article

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

May 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMy Dog Likes It Here

May 1978 By COREY FORD -

Article

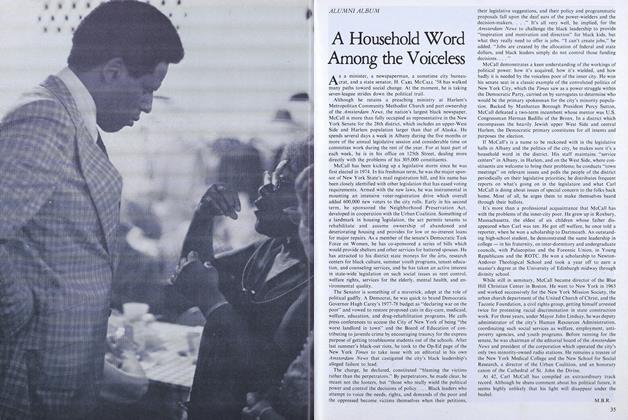

ArticleA Household Word Among the Voiceless

May 1978 By M.B.R.

Anne Bagamery

-

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES1978

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By Anne Bagamery -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES1978

JULY | AUGUST 2023 By Anne Bagamery -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES1978

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2023 By Anne Bagamery -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES1978

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By Anne Bagamery -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES1978

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By Anne Bagamery -

CLASS NOTES

CLASS NOTES1978

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2025 By Anne Bagamery

Features

-

Feature

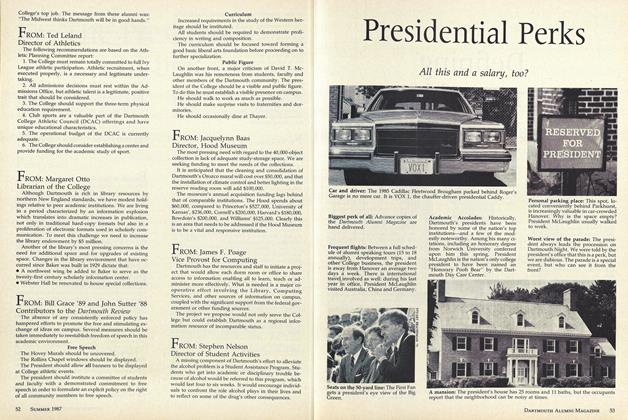

FeaturePresidential Perks

June 1987 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryStimulating Poison

MARCH 1995 By George Hoke '35 -

Feature

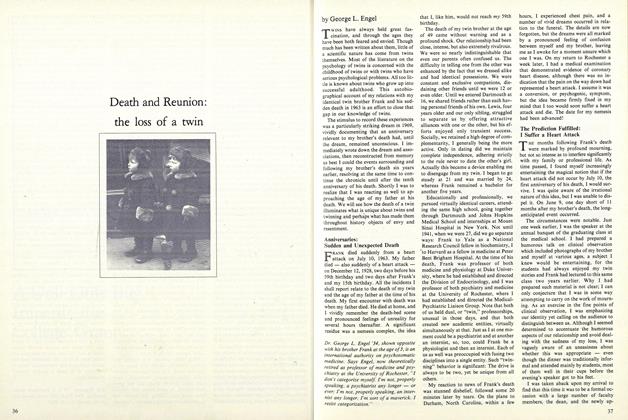

FeatureDeath and Reunion: the loss of a twin

June 1981 By George L. Engel -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Mar/Apr 2005 By Gray Mercer '83 -

Feature

FeatureFuturescapes

May 1974 By R.B.G. -

Feature

FeatureThe Mold

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Warren Cook '67