Dartmouth architecture in our time

THE importance of architecture to a college's image cannot be overestimated. When we remember a place, we envision the setting and the buildings that are the physical manifestations of the less tangible presence we call spirit.

Dartmouth would hardly have achieved its present popularity and its national image (nor would alumni recall the "Halls of Dartmouth") had the College not cared something about the quality of its architecture. It is difficult to imagine students and graduates writing songs or dreaming about quonset huts or the cheapest possible cinder-block shelters. Perhaps there are schools where indefinable spirit compensates for the lack of an attractive setting, but how many major institutions would fit such a description?

Architecture, for example, was uppermost in the mind of Thomas Jefferson when he founded and built the University of Virginia. Jefferson was not only attempting to produce a living classroom by employing different classical styles for the university's buildings, he was creating an image that would help his struggling school to compete against older, more established institutions. Today, when we think of the University of Virginia - and maybe even refer to it as a "great university" - we visualize Jefferson's incredibly rich architectural setting.

Similar reasoning can be attributed to Woodrow Wilson and the trustees of the small, out-classed College of New Jersey, when, in 1896, they declared that Princeton would become the "Oxford of America," and that henceforth all new buildings would be constructed in the Gothic style. In good times and in bad, Princeton, with its scholarly adaptations of Merton and Magdalen, has "looked like" a great university. Its links with the past, whether stage-setting or not, have continued to attract outstanding teachers and students. Not surprisingly, Princeton's recruiting films have always relied heavily on shots of that dreamlike American recreation of Oxford.

It is easy to be amused by such antics as Yale erecting a quadrangle employing Gothic styles from four centuries to make it appear that it had evolved slowly in the Middle Ages, or the sandblasting of steps to imply that generations of Yale men have trod there. Such deliberately arcane practices may seem like unnecessary or even deceitful play-acting when placed against the needs of scholarships or books. But for schools like Yale, or Princeton, or Duke ("instant Princeton"), such attention to visual effect has proved good public relations and an excellent investment.

Dartmouth, too, decided on an image: the Georgian of 18th-century England and her American colonies. In the early 20th century, the College downplayed its few Victorian buildings while erecting handsome brick structures combining elements from Tidewater Virginia plantations, Independence Hall, and, of course, Harvard.

Baker Library was not so much important as new space in which to expand the College's growing library (which it did, and did well), but as a concrete symbol - a respectable image identifying Dartmouth with its pre-Revolutionary past. No one who read "Castles in the Clouds," the recent ALUMNI MAGAZINE article featuring the exquisite and grandiose renderings of former College Architect Jens Fredrick Larson, could doubt the effectiveness of a unified stylistic program. In short, architecture has been able to give age, respectability, and legitimacy to Dartmouth far faster than innovative but less visible developments in, say, curriculum and educational philosophy.

But what about architecture at Dartmouth in our own day?

THE Great Depression, and then the Second World War, signaled an end not only to Larson's masterplan for Dartmouth, but of the high level of craftsmanship needed to erect such elaborate and detailed exercises in the Georgian style. The Modern Movement, with its frontal attack on "eclecticism" and its emphasis on a universal functionalism, also spelled doom for the Georgian buildings modeled on the work of Sir Christopher Wren and Charles Bulfinch.

Dartmouth's pre-war buildings remain to maintain the traditional image, but new architecture must also play its part. It, too, will be judged on its effectiveness in defin ing the physical presence of the College. While schools such as Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, and even the New York State University system have dazzled the international design community with their sponsorship of the world's best architects, Dartmouth has generally decided on a less adventurous, more conservative program for new architecture.

However, very much to Dartmouth's credit are the two buildings that were designed by the Italian engineer-architect, Pier Luigi Nervi: Leverone Field House and Thompson Arena. These creations by this 20th-century master put Dartmouth on the architectural map.

Leverone, which is impressive by its sheer size alone, was Nervi's first work in the United States. Both it and Thompson Arena show 'the designer, who refers to himself as an engineer, not an architect, demonstrating how purely functional buildings - in the tradition of bridges, airplane hangars, and factories - can be bold and exciting. (Nervi's Dartmouth works were discussed at length by Professor John Jacobus in the January 1976 issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.)

These two concrete triumphs aside, Dartmouth's contemporary architectural I.Q. is not very high. Architecture's rather low ranking in the College's scheme of things is shown by the fact that, with the exceptions of Nervi and his fellow engineer, Buckminster Fuller, Dartmouth has awarded an honorary degree to only one architect in its history: Wallace K. Harrison.

Harrison (referred to in the profession as the "Rockefellers' favorite-architect") was once considered a fairly avant-garde architect, back in the early days of Modernism, when he was involved in the design of Rockefeller Center and the United Nations. However, by the time he designed Dartmouth's Hopkins Center in the early 19605, he had become a sort of blue-chip corporate architect who produced "safe" buildings for unadventuresome clients.

There can be no denying the importance of Hopkins Center and what it has meant to the Dartmouth community, but as architectural design it is a trite, even boring container for the far more exciting activities that take place within it. Its main facade is an echo of the front of the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center in New York, on which Harrison was concurrently working. It even features the same five-arch motif that Harrison unimaginatively borrowed from the Vienna Opera.

Hopkins Center, in its use of brick, did maintain the prevailing material of most of the College's buildings, and its low mass deliberately does not compete with Dartmouth Hall or Baker Library. While we can be grateful that the building functions as well as it does, compared to the exciting arts centers of other-schools - Wesleyan's new arts complex by Kevin Roche, for example - it is a businessman's idea of culture, rather than the sort of creative artistic solution that one would expect of a first-rate college.

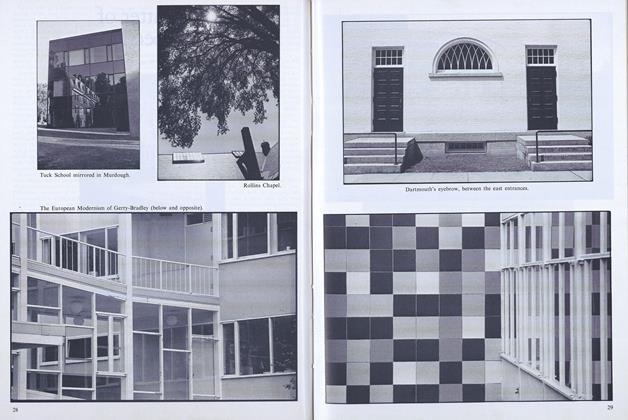

A much more radical departure in both materials and style is the mathematics-psychology building (Gerry-Bradley) designed in 1961 by a then Dartmouth professor and his architect wife, E. M. and M. K. Hunter. The mathematics-psychology building is a full-blown example of the International Style, employing almost the complete vocabulary of that universal mode: strip windows, sunscreens, flat walls and flat roofs. While some people may not like the green, turquoise, and white tile used to face the main staircase and the end wall of Bradley, the building is a good representative of Modernism, especially of the 19305, European variety.

In fact, the mathematics-psychology building may be appreciated by future historians as something of a period piece, illustrating a time and an architectural philosophy that ignored people's natural love of ornament, and that showed a disdain for surroundings and environmental considerations (flat roofs and sunscreens are not ideally suited to the climate of northern New England). Later buildings on campus can be seen as a reaction to the form-follows-function aesthetic of Bradley and Gerry halls.

Similar in style to the mathematicspsychology building, the Choate Road dormitory complex of 1958 also features flat roofs and an absence of ornament, as well as reference to the work of the leading teacher of the International Style, Walter Gropius, particularly his Harvard Graduate Center of 1949. However, the stripped-down functional quality of the Choate dorms has been softened by two decades of Hanover winters and growth of plantings, making for a pleasant and unobtrusive academic enclave.

The architects who designed the Choate Residences, Campbell, Aldrich & Nulty of Boston, were also responsible for the three dormitories on Wigwam Circle in 1962. Later renamed with the much less appealing titles of French, McLane, and Hinman halls, these buildings have an unusual Y-shaped plan, an ingenious layout that allows each room to have a better view than would be possible through employing a rectangular box-like configuration. But even with this unusual plan, the Wigwams, especially with their kitsch colored-glass entrances, could be mistaken for a Holiday Inn, causing one to ask why would a student want to attend an Ivy League school and live in a motel?

Across the way from the Wigwams, Channing Cox Hall (also designed by Nelson Aldrich) is equally commonplace. Yet, its asymmetrical fenestration and its very plainness may be a conscious effort to emulate the so-called "Philadelphia School" style, made popular by Robert Venturi, Charles Moore, and other Post-Modern architects.

But, only half a dozen years after the Wigwams, Campbell, Aldrich & Nulty built a new residence for Tuck School that is a handsome and very satisfying composition. It is clearly contemporary, yet by its use of sympathetic materials, scale, and massing the new dorm blends in well with its neo-Georgian neighbors. (Campbell, Aldrich are also responsible for Strasenburgh Hall, a dormitory at the Medical School, which is also humanly scaled and has an interesting visual rhythm.)

Tuck School's Murdough Center, also by the same firm, is an obviously new building that fits in well with its architectural surroundings. Like Cox Hall (but more successfully), Murdough depends upon plain, simple massing for effect. Unfortunately, its best side is that which faces away from Tuck Drive and the campus, where the flat walls and flush glazing create a more satisfying composition than exhibited by the more public front. Murdough, while an attractive design, is marred by weak detailing, by an unnecessarily bleak interior and the impression of inexpensive construction.

A case can be made for the College's depending upon architects used previously and who are familiar with the school, rather than choosing big-name architects for their own sake. Such firms often provide retakes of other buildings they are doing elsewhere at the same time, as already seen with Hopkins Center.

Another instance of this practice is the design by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill for the Kiewit Computation Center of 1966. SOM, perhaps the largest architectural firm in the country, were the leading corporate designers of the 1950s and early sixties. They were known for such precision engineered works in steel and glass as the Lever House in New York and the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. However, by the mid-1960s their style became excessively mannered as the firm, turning to more Formalistic, even classically-inspired formulas, all but abandoned the glass boxes with which they were so closely identified.

Kiewit, with its tapered columns supporting simple steel box members, is a modern recreation of a Greek temple. But Kiewit would seem to be a spin-off from SOM's Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale of the same date, although here the columns are rather ungainly and the building lacks the refinement of its model. Instead of a botched cloning, Dartmouth deserved and should have demanded a totally new design.

Dartmouth's largest building project both in size and cost has been the various buildings for the Medical School erected since the early 19605, mostly by the respected Boston architectural firm of Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott. Even though the design of medical school buildings tends to be restricted by carefully defined medical and teaching functions, that should not preclude the possibility of good new architecture. Alas, the Vail building is the only part of the Medical School that is even vaguely interesting. And, given the Medical School's attractive, almost rural setting, the entire complex looks rather like a big city hospital on a constricted lot.

However, if the Medical School is a visual disappointment, the Shepley firm - whose antecedents include Henry Hobson Richardson, namesake of the Richardson Romanesque style of which Rollins Chapel is a prime example - produced an absolute winner in its Sherman Fairchild Physical Sciences Center pf 1974.

WEDGED between the Georgian buildings of Wilder and Steele, Fairchild is a suave and vigorous exercise in steel, glass, and rough concrete. Actually, it is composed of two separate wedge-shaped buildings around a full-height, five-story open court. This atrium gives a very spacious feeling, and the exposed concrete beams and variety of protruding angles provide much visual interest. The intriguing east wall sets a glass envelope about six feet from the interior concrete wall. In short, Fairchild is the sort of new architecture of which the College can be justifiably proud, and which it should be building.

With the notable exception of Fairchild, most of the new buildings at Dartmouth tend to be safe rather than visionary. They are more like the stolid buildings that accompany the advertisements in architectural journals, rather than those in the featured articles. But perhaps there is a good case to be made for erecting structures that do not shout for attention by their novelty and that do not openly compete with Dartmouth's justly famous setting and older buildings.

INSTITUTIONS, like people, are not static. They grow and change, and often alterations or the destruction of older buildings tell us a great deal about changing attitudes toward culture and particularly the built environment. But there is hardly any excuse for the philistine approach to the past as demonstrated by certain recent renovations at Dartmouth.

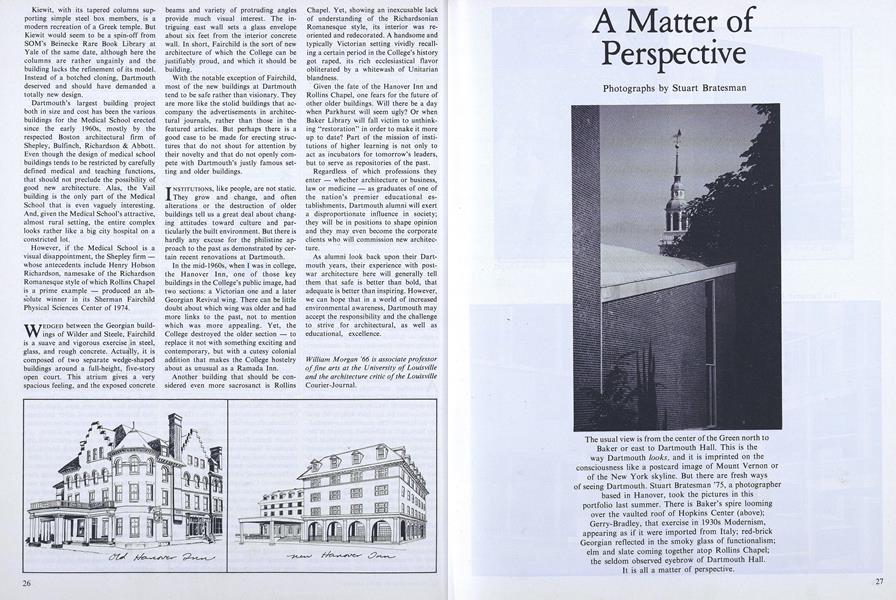

In the mid-19605, when I was in college, the Hanover Inn, one of those key buildings in the College's public image, had two sections: a Victorian one and a later Georgian Revival wing. There can be little doubt about which wing was older and had more links to the past, not to mention which was more appealing. Yet, the College destroyed the older section - to replace it not with something exciting and contemporary, but with a cutesy colonial addition that makes the College hostelry about as unusual as a Ramada Inn.

Another building that should be considered even more sacrosanct is Rollins Chapel. Yet, showing an inexcusable lack of understanding of the Richardsonian Romanesque style, its interior was reoriented and redecorated. A handsome and typically Victorian setting vividly recalling a certain period in the College's history got raped, its rich ecclesiastical flavor obliterated by a whitewash of Unitarian blandness.

Given the fate of the Hanover Inn and Rollins Chapel, one fears for the future of other older buildings. Will there be a day when Parkhurst will seem ugly? Or when Baker Library will fall victim to unthinking "restoration" in order to make it more up to date? Part of the mission of institutions of higher learning is not only to act as incubators for tomorrow's leaders, but to serve as repositories of the past.

Regardless of which professions they enter - whether architecture or business, law or medicine - as graduates of one of the nation's premier educational establishments, Dartmouth alumni will exert a disproportionate influence in society; they will be in positions to shape opinion and they may even become the corporate clients who will commission new architecture.

As alumni look back upon their Dartmouth years, their experience with postwar architecture here will generally tell them that safe is better than bold, that adequate is better than inspiring. However, we can hope that in a world of increased environmental awareness, Dartmouth may accept the responsibility and the challenge to strive for architectural, as well as educational, excellence.

William Morgan '66 is associate professorof fine arts at the University of Louisvilleand the architecture critic of the Louisville Courier-Journal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureConundrum of the Gridiron

October 1978 By Jack DeGange -

Feature

FeatureA Matter of Perspective

October 1978 -

Article

ArticleSignal-Caller for the Hurt

October 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

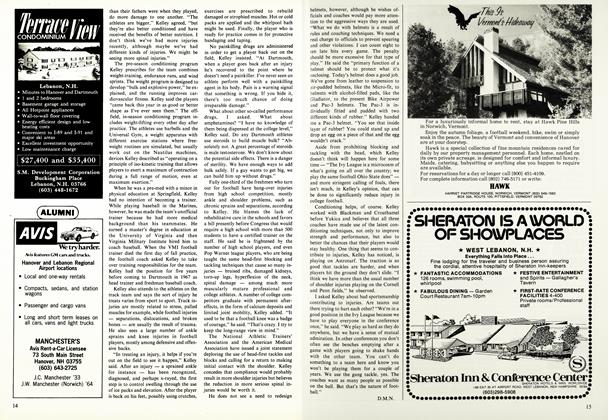

ArticleOffice of Development Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1978 -

Article

ArticleSire of the Sitcom

October 1978 By M.B.R.

Features

-

Feature

Feature1957 Alumni Fund Reaches New High of $928,592

October 1951 -

Feature

FeatureSpace Salesman

DECEMBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Honors Seven

JULY 1971 -

Feature

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

MARCH 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Left Fielder's Glove

March 1996 By JOHN MONAHAN -

Feature

FeatureIn language teaching, a call for ‘madness'

February 1974 By R.B.G.