Mid-winter seemed like an appropriate time to visit our neighbors a mile or two up the Lyme Road at CRREL — the Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory — which has been in Hanover since 1962. Interested in just about any engineering application in cold climates, the 275 people who work there have been particularly involved in civil-works programs, like Alaska pipeline construction and a technique for applying sewage waste waters to land, for example, as well as design work for the early warning radar system in Greenland and Alaska and ice-core studies in Antarctica.

We heard they had almost finished building a $7.5-million 160- by 200-foot two-story experimental icebox and we wanted to look around before they plugged it in.

S. L. DenHartog, one of the scientists who will be doing research in the Ice Engineering Facility, as it is called, tossed us a hard hat and gave us a tour. He told us the lab was designed as a facility for working out solutions to such expensive winter problems as flooding caused by ice jams; ice damage to bridges, docks, and shoreline properties; interference with the supply of water to hydro-electric plants; and icerelated navigation hazards. It all adds up to something like $200-million worth of trouble a year.

Projector Director Ginnie Frankenstein had been wanting a laboratory large enough and cold enough to carry out controlled experiments with real ice and largescale models of waterways. After a few years of proposal writing, politicking, and planning, construction began in May 1976 on a lab that far surpassed the oversized refrigerator originally hoped for. "We did a more convincing job than we thought," DenHartog said.

Most of the studies will be conducted in the 80- by 160-foot cold room capable of maintaining temperatures anywhere between +65 and -10 degrees. This big icebox, with its sophisticated accouterments, will be an ideal place to study the cold-weather performance of machinery and buildings, to test the strength of large ice sheets, and to construct scale models of riverbeds.

Another research area, the test basin, consists of an eight-foot-deep 30- by 150-foot tank for growing and studying the formation of ice sheets, for measuring the pressures they exert, for building models of canal locks, and for testing the designs; of structures as diverse as icebreaker hulls and bridge piers. A large hopper at one end of the pool feeds the used ice into a melting vat while pipes route the water back to the other end for re-freezing.

The refrigerated flume is a 120-foot glass-sided channel, two feet deep and four feet wide, that can be tilted to create varying degrees of flow, up to 14 cubic feet per second, simulating water and ice movement in a river. The flume is designed to freeze from the bottom up, making it easier for observers to study the bottom of an ice sheet while it is forming. The device is expected to prove particularly useful for sediment-scouring studies and for observing the formation of frazil ice - small crystals that amass in moving water and latch onto protrusions, creating underwater dams.

Offices for about 15 technicians and scientists who will inhabit the warmer reaches of the edifice won't be heated by a furnace, since there isn't one, but by a system distributing waste heat produced by the refrigeration of the laboratories. Each of the three experimental areas is surrounded by eight inches of insulation in the walls and six inches of insulation on top of the roof, a rubber membrane that doubles as a vapor barrier and stretches in response to fluctuations in temperature.

Denhartog explained that government work, of course, has first priority in the lab, and that CRREL already has a long list of projects, most of them actually related to, public works. But there's a good chance, he speculated, that as space and time becomes available, scientists will be able to make arrangements to conduct private research at the facility.

And we thought the labs in the physics building were cold.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

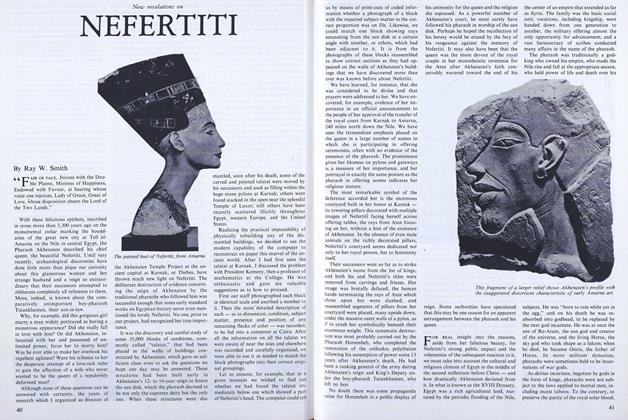

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R.