Converting an atheist traveler and a skeptical professor

I live in Montana, to a certain extent a culturally deprived area where any object of art not in the style of Charles M. Russell or Frederic Remington is considered unworthy (if considered at all). I have grown to regret the wasted opportunities of my undergraduate years (one art history course) and later the war years, during which I spent three or four weeks on leave in Florence without once setting foot in the Palazzo Uffizi or the Academy Gallery or giving the cathedral more than a glance.

It is probably for just such louts that the Alumni College designs its courses. One uniquely tailored for me, on the art of Italy from ancient Rome through the Renaissance, was discovered by my wife Jean through an ad in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Off we went to Italy to discover there is more to Art than French impressionism or Jackson Pollock (or Remington), arriving in Rome via Alitalia in early October 1978. The course, taught by Classics Professor Edward Bradley, with a small (18) congenial group of alumni and their friends, convened at the Hotel Leonardo da Vinci just after the death of John Paul I. Our first venture was to pay last respects to the Pope in a sad funeral march through Bernini's magnificent colonnade around St. Peter's Square, past Michelangelo's Pieta to John Paul's bier under St. Peter's dome in the heart of the Vatican. What was a card-carrying atheist doing here I wondered.

Edward Bradley proceeded to show me, leading us through the architectural maze of ancient Rome and the Early Christian churches. He began in the Roman Forum with a provocative discussion of what the Forum meant to a Roman citizen, waxing downright emotional on the Roman institutions of commerce, politics, and religion, restoring the cold ruins to their ancient splendor as he led us through the Arch of Titus and along the Sacred Way. He ended our Roman study several days later in the Pantheon with an equally impassioned lecture on the philosophic intent of its architect in creating a monument to Roman religious belief.

Somewhat to my dismay, we had continued in Rome with a pilgrimage through the Early Christian basilicas, which appeared to be more religion than art, a shameful revelation of my bigotry and provincialism. But where else could one look? My fellow travelers goodnaturedly tolerated my ignorant brashness until the light gradually dawned and I plagued them no more.

Edward Bradley's passion related to all things beautiful as he made us view, through early Christian and Renaissance eyes, the architecture with its focus on the apse and altar beneath the soaring space of clerestory and dome. Here also were the works of the later masters: Caravaggio, Michelangelo, Raphael, Perugino. We returned to St. Peter's Cathedral (now full of scurrying cardinals reconvened for the election of John Paul II) and the Sistine Chapel as our Roman holiday ended. I might add editorially (and heretically) that the Sistine Chapel, with its complex, overwhelming ceiling of Michelangelo frescoes—but filled with rain-soaked tourists and their guides—was not the magnificent interior I expected. Perhaps with less humanity and a little more sunlight, it would appear more ethereal. I intend to return under more favorable circumstances to find out.

The tourist life in Rome; one rainy night, we left our hotel for a highly touted restaurant, taking two cabs, showing our driver the written address. It was the rush hour, with hundreds of Fiats all driving at grand prix speed in the downpour. As the congestion grew, we shunted to smaller and smaller streets filled with increasing numbers of cars until everything ground to a tumultuous and permanent halt. We abandoned our cab and sloshed damply forward under the leadership of Dr. Nick Vincent,, who shoved the address under Italian noses every half block, advancing only as far as visible hand directions would take us. Miraculously, but chiefly through the perseverance of Nick, we arrived to find our advance group already warmed with wine and on intimate terms with the proprietor. An excellent and jolly meal in the subterranean, barrel-vaulted ruin of an ancient Roman theater followed, costing no more than it might have at "21," New York.

We left Rome for the hill towns of Tuscany in blessed sunshine, stopping for the night in the ancient Etruscan city of Orvieto with its famous Gothic cathedral. This is an astounding and beautiful church with a soaring mosaic facade, black and white horizontal stripes inside and out, with a contemporary (modern art) bronze door, and in the transept marvelous but bizarre 15th-century frescoes by Angelico and Signorelli depicting heaven and hell, the resurrection and the antichrist.

Ironically, in Florence we put up at the same hotel in which I had wasted my youth during the Italian Campaign of 1944-45. For two days, we followed our leader throughout Florence, concentrating on the works of the great Renaissance architect, Filippo Brunelleschi, creator of churches noted for their spatial serenity. His church of Santo Spirito and the Pazzi chapel engendered another fervent exposition on the philosophy of church architecture by Bradley. The professor held us spellbound.

A visit to the Academy in Florence and the Uffizi Gallery cannot be omitted from this log. There is something eerie in confronting famous works of art one has seen and read about in art history books. Michelangelo's David gave me chills even though we could hardly get close enough to touch it because of the crowd paying homage to the second most famous statue in the world (would you accept Venus de Milo as numero uno?). The first room in the Uffizi Gallery contains the three huge and renowned Madonnas With Child of Cimabue, Duccio, and Giotto (again chills). Thereafter, room upon room of famous masterpieces casually displayed in the old palace: Michelangelo, Raphael, Leonardo, Botticelli, Titian. It was emotionally exhausting, and we had to stop after an hour or two, returning gratefully to the old hotel and the warm chatter of our new friends.

On to Ravenna by bus across the spine of the Appenine mountains, teetering dizzily up and down the switchbacks to the littoral piain of the Adriatic. It is a seaport filled with drab looking brick churches built by the Roman Emperors West for their new seat of government, moved to Ravenna to escape the barbarians while Rome was being sacked repeatedly during the fifth century A.D. The splendor of Ravenna lies in the dazzling mosaics that fill its churches, a continuation of the Roman idea of the development of inner space with only a suggestion from the unpretentious outside. Made of small pieces of colored glass (tesserae), they give a shimmering, luminous illusion of unreality which, along with the primitive abstraction of early Christian art, is utterly pleasing to this lover of modern art.

By now, we were a close-knit group enjoying each other's company without wallflowers or favorites. We bussed to Assisi via San Marino, an independent city-state on an escarpment (and noted chiefly for its duty-free whiskey), an uneventful trip except for an hour stalled in the dark on a lonely mountain road, allegedly out of gas. Assisi, the home of St. Francis and site of the Franciscan Monastery, attracted many early masters of the late 13th and early 14th centuries, including Cimabue, Giotto, Simone Martini, and Pietro Lorenzetti, all of whom painted frescoes in the upper and lower churches. Particularly powerful are the "Giottesque" panels in the upper church, depicting scenes from the life of St. Francis originally ascribed to Giotto but in recent years suspected as done by his pupils. Since returning home, I have been told by an art historian from New York's Metropolitan that they are again felt to be by Giotto himself. It is strange how this information affects my critical eye; art snob that I am, I looked on those panels as great paintings, forceful, simple, with large areas of flat color, so characteristic of contemporary painting, yet somehow flawed because they were not by Giotto's hand. When I see them next time, I'm sure they will seem totally magnificent.

The last few days approached too fast as we traveled luxuriously to Sorrento in our roomy bus with many extra seats, taking a rest stop at Monte Cassino to gape at that huge mountain scaled by the Allies in driving out the Germans. Everything, including the famous Benedictine Abbey, has been totally restored with no evidence of that bitter battle remaining.

From our gracious old hotel in Sorrento, we made the traditional trip to Capri, including the Blue Grotto with its swarm of vying boatmen and a breathless hike to Tiberius' villa, where we lunched on bread, fruit, cheese, and wine in a charming café with a precipitous view of the Mediterranean 2,000 feet straight down. Unfortunately, the ruins were closed on Mondays, but the custodian was "delightfully corruptible" (Edward Bradley), so we had it to ourselves for a modest fee. This was a beautiful site, especially if one visualized the terraced colonnades and gardens of Tiberius' time.

Two days commuting from Sorrento to Pompeii ended our odyssey. That marvelously preserved city returned to life through the dissertations of our professor once we had craftily ditched our mandatory Italian guide. We met our undergraduate counterparts (the current Dartmouth students studying in Italy) with their instructor in Pompeii's forum and briefly renewed friendships begun at a cocktail party in Rome.

Most memorable in Pompeii were the paintings in the Villa of Mysteries of the secret cult of Dionysius. While most of the paintings in the city are rather crude, these are exceptionally well done and worthy of our new found respect for Roman art.

After a night of quiet revelry, we departed for home "all Pompeied out," as punned Dr. Walt Dittmar, our pleasant low-key comic and friend.

SLEET was spitting against the windowpanes as I left my home in White River Junction one evening late this past February and headed for Hanover to attend the first reunion of the Dartmouth Alumni College seminar in Italy. With me were my wife, my father, and my stepmother, yet none of us had ever attended Dartmouth as an undergraduate. What made the evening even more unusual was the fact that never before had I attended an academic reunion of any sort. Wretched weather and a 20-year-old private tradition notwithstanding, off we went to join in a delightfully light-hearted and sentimental renewal of ties with ten other alumni and alumnae of our program, most of whom had never met one another before our journey last October.

The enthusiastic narrative written by Bruce Anderson '43 offers a generous measure of the success of our seminar in Italy from the perspective of a student who was initially rather skeptical of certain aspects of the syllabus. I want to offer a brief account of my own progress from a different kind of skepticism to the realization that the experience of the Alumni College was one of the most pleasant and fruitful personal and academic ventures of my entire career. Only in such terms can I begin to account to myself for my delight in overcoming all former scruples by attending a Dartmouth reunion two months ago.

Our Alumni College seminar was born in the fall of 1977, thanks to the imagination of Lee H. Potter '78 and the encouragement of Jerry Mitchell '53 of the Dartmouth Travel Bureau. My own willingness to participate was dictated primarily by two simple and rather selfish motives. The first was my private conviction that the Roman Foreign Study program offered by the Department of Classics for undergraduates from all departments of the College, and not only for classics or classical archaeology majors, is unique to American higher education arid, what is more important, that it is one of the most intellectually significant courses of study in the Dartmouth curriculum. It involves the systematic and formal investigation of the principal monuments, sites, and artifacts of the Etruscan and Roman cultures in Italy from the eighth century B.C. up to the mid-sixth century A.D. All of the work of the program takes place in situ; lectures and discussion are held in the open air, rain or shine.

This learning in a radically different key has led to gratifying results for both students and faculty ever since the inception of the program in 1971. To put it plainly, I wanted the opportunity to share the experience more broadly with those friends and alumni of the College whose understanding and support are absolutely necessary if the College desires to continue to offer academically strong foreign study programs, which, as it happens, are also rather expensive. My second motive was my desire to have a holiday in Italy with genial companions during the most benign season of the Italian year.

These two motives, initially uncluttered in my own thinking, gradually became overshadowed with complexity and some doubt as the date for the beginning of our program drew near. Dreams of an autumnal holiday in Italy faded away as I realized that my wife would not be able to accompany me; someone, somewhere, had to take care of our two small children, and the nearest grandmother was herself going to be a member of our seminar! In addition, preparation for the seminar was becoming more intensive as I focused more sharply on the fundamental academic purpose of the program. These were real students, whatever their ages and backgrounds, who had enrolled for the program; some of them I knew well and respected highly; two of them were my own ather and stepmother. This meant that my lectures had to correspond, to the best of my ability, to the attractive publicity which had drawn so many interested participants to the program.

There was also growing doubt in my mind that I could sustain the intellectual interest of my students during a period of three weeks in a country rich in so many conflicting claims on even the most academically zealous. I had troubling visions of increasing distraction in the ranks as one after another of the seminar members would begin to look avidly at Italian woolens and leather goods even while I saw myself disserting learnedly, and probably tediously, on the glories inherent in great lumps of brick-faced concrete lying in weeds, the inert relics of monuments which had once attested boldly to the genius of Roman architecture. Frankly, my visions became almost nightmarish.

I was entirely wrong in every way. Unlike undergraduates for whom foreign study can be and often is only the beginning of a lifetime of opportunities for all kinds of growth, the members of my seminar approached their stay in Italy with the understanding that such an experience was likely to be unique. They knew without illusion what they didn't know and also what they wanted to know and therefore brought to their learning an unusually keen appetite and enthusiasm. From their own lives they also drew broad and deep experience of so many things beyond the ken of undergraduates that the level of discussion in "class" as well as at regular evening gatherings for cocktails or at dinner was consistently spirited, discriminating, farranging, and always tempered with good humor. I found the companionship of my "students" marvelously provocative and refreshing.

The self-selecting nature of the seminar, furthermore, led to the formation of a group of participants who had already chosen in advance to devote themselves, at least theoretically, to understanding the meaning of those very ruinous lumps of concrete about which I had fretted anxiously. They were, in fact, not even daunted by rain, often torrential, when we visited during the first wet days of the program all kinds of monuments and sites which even under the best of conditions require unwavering faith and solid archaeological knowledge for their full appreciation.

By the time we headed north from Rome for Orvieto and Florence, we had developed a strong esprit de corps and a clear perception of our academic orientation. Diligent note-taking coupled with mental cross-indexing of a growing number of styles, monuments, and works of art generated keen exchanges after lectures and free debate on topics as varied as the nature of God and religious faith, the purpose of art, and, of course, the present condition of Dartmouth College. Here, at last, was a class for whom learning spilled exuberantly out of the classroom, into the bus, over the dining table, and even up to the palatial aerie of Tiberius on the island of Capri.

In drawing attention to the intelligence, tolerance, and remarkable adaptability of the group to various aspects of the program in Italy, I realize that I run the risk of appearing somewhat condescending. It may even be true that before the program began there was more than a touch of condescension in the very anxiety with which I anticipated, mistakenly, the development of academic and cultural conflicts in Italy. But my intention is not so much to pay a superfluous compliment to the students of the seminar as to underscore my wonder and pleasure at the ease with which the individual members of the group, including myself, drew together to share fully the adventure of our three- week odyssey up and down the Italian peninsula.

We all worked hard. We faced in common the frustrations of occasionally discouraging weather, mechanical failure at dusk in the rural isolation of the Umbrian mountains, and many a wrong turn on the part of our genial but casual bus driver, who inadvertently led us on a tortuous detour through the shimmering, autumnal landscape of the Chianti winegrowing region of Tuscany, even as we thought that we were destined for the ever-elusive city of San Gimignano. There was, in fact, an occasion on which a comfort stop brought us face to face with plumbing so primitive that endurance seemed the better part of nature. Yet somehow all these events were transformed into the very stuff of the program and thereby into the core of an experience which held us together as much in Italy as it does even now in the United States.

What was it, then, that drew me as professor to the reunion in Hanover last February? I believe that the answer lies in my having learned two important lessons. Before the seminar in Italy, I had not known how intellectually vigorous and challenging adult students could be; collaboration with them greatly expanded my own sense of the possibilities of teaching and learning, and I am grateful to them for having freed me of my own undergraduate parochialism. I had been rather cynical, furthermore, in my attitude toward what is commonly and rather tritely called "the Dartmouth family." I still loathe the expression, yet I admit unashamedly, even though I may choose to use different words, that the experience in Italy with graduates and friends of Dartmouth College generated a special form of fellowship, at once intellectual, spiritual, and social, which lies as close to my own ideals of learning as I can imagine.

The discontinuities characteristic of life at the College for both faculty and students make such fellowship, alas, very difficult to achieve in Hanover. The Alumni College seminar in Italy was for me, as I hope for the others, a rather privileged moment which I would repeat with pleasure as often as possible. However limited its form, the reunion in Hanover last February was one such renewal which perpetuates some of the ideals I consider to be Dartmouth's proudest treasures.

Orvieto: new balcony, ancient buildings.

Assisi: bell tower of St. Peter's.

L. Bruce Anderson, a member of the "warclass" of 1943, practices medicine inBillings, Montana.

The reunions Professor Bradley hasavoided for 20 years are those of Yale,where he earned both undergraduate andgraduate degrees. He joined the ClassicsDepartment at Dartmouth in 1963.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThere and Back Again

April 1979 By John S. Major -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleJust Out of Reach

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleBooks in Process

April 1979 -

Article

ArticleMoney Man

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOn the Raising of Spirits

April 1979 By MICHAEL DORRIS

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureBURNLEY

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureIntegrity

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Jayne Daigle Jones '86 -

Feature

FeatureFirst

MAY | JUNE 2016 By Judith Hertog and Lexi Krupp ’15 -

Feature

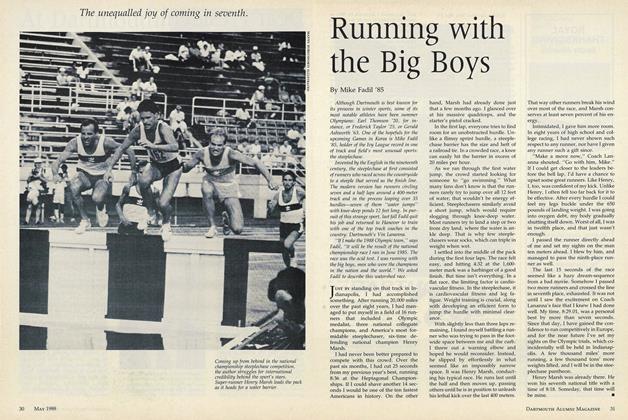

FeatureRunning with the Big Boys

MAY • 1988 By Mike Fadil '85 -

Feature

FeatureA Billion Dollars

NOVEMBER 1996 By Rebecca Bailey