A friend we knew at Vaughan School, which is in Michigan, and at Dartmouth writes:

When Stephen V. F. Waite — Hanover selectman, classicist, and computer expert at the Kiewit Center — announced an international conference on computers and the humanities, I wasn't surprised. As a loyal reader of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, I already knew that computers were used at Dartmouth to take Hemingway's prose apart and to put back together the fragments of an Egyptian temple.

A week at Dartmouth in August showed me that computers are used for lots of other things, too. Computer music, for instance. Professor Jon Appleton — director of the Bregman Electronic Music Studio at the College — arranged for an evening of "New Music with Computers" at the Hopkins Center. To my surprise, the concert wasn't a ho-hum technical display but an exciting musical event in which performers (especially Appleton on the Synclavier) were more important than the programmers. The best pieces combined music with a live dancer (Elisabeth Appleton, principal dance instructor at Dartmouth) and music with a live soprano: real people in a dialectic with synthetic sounds.

The conference demonstrated just how helpful computers can be in helping scholars keep track of things. Computer memories are more reliable and a lot bigger than human memories, and humanists have come a long way from having all knowledge in their heads, or in their hats, or in boxes of file cards. For dictionaries — for instance, the Dictionary ofAmerican Regional English and the Dictionaryof Old Spanish — all the information is kept handy in the machine to let the lexicographer spend human energy figuring out what it all means. With properly constructed files, scholars can get prompt answers to questions about medieval iconography: "What animals are shown getting aboard the Ark in frescoes and illuminations, and when do we find the first evidence of the exotic animals brought to Europe by African and Asian explorers?" Or questions about the actors performing on the London stage: "When and how often did Garrick play in Shakespeare with Mrs. Siddons?"

Computers are good for dissecting and assembling all sorts of things. One literary man — Dartmouth '56 — fabricated some 14th-century Chinese poetry, not because he wanted more poems but because he wanted to test his description of the rules for making the poetry. If the computer poems weren't very good, he hoped to find what he had left out of his computer-driven recipe. Other people reported analytic (rather than synthetic) techniques'for getting into the hearts of art works to see what's ticking: Joyce's Ulysses and Euripides's meter, for example.

Sometimes the questions seem a little silly, but they are so easy to ask that they get asked anyway. For instance, a psychologist from Maine showed the ups-and-downs of style in poetry. But what matches the patterns of ups-and-downs? "Primary process content" in English poems — things like "defensive symbolization" and "Icarian imagery" — turns out to correlate with the weather. Over long climatic periods, when the west wind blows in England, the temperature goes up and so does poetic "primary process content." "O wild West Wind," wrote Shelley (correctly sensing the way the wind was blowing). Hamlet had the idea, too: "I am but mad north-north-west; when the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw."

In Hanover in August the wind came from the northwest. The place was full of hawks and handsaws, but it was hard to tell them apart.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTwo at the Top: On being a woman, a wife, a partner

October 1979 By Jean Alexander Kemeny -

Feature

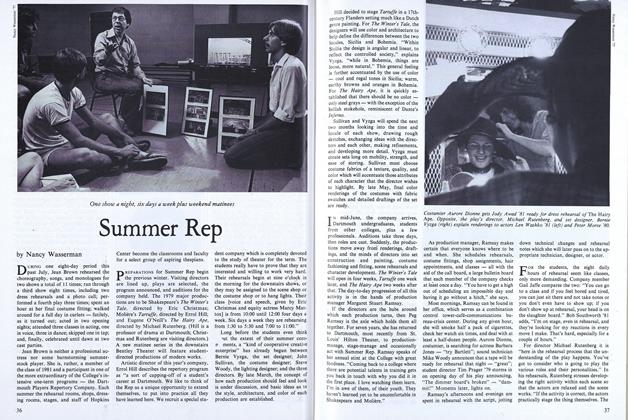

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Article

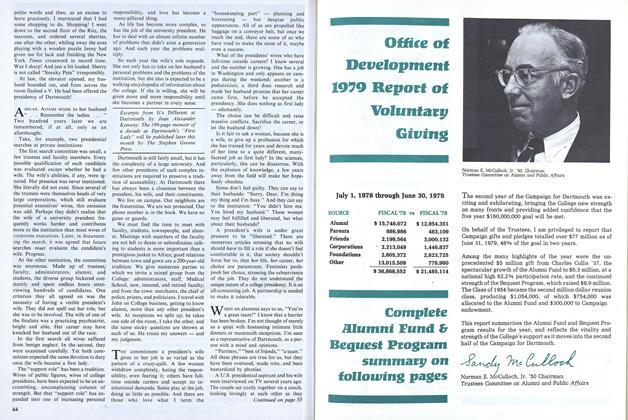

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Article

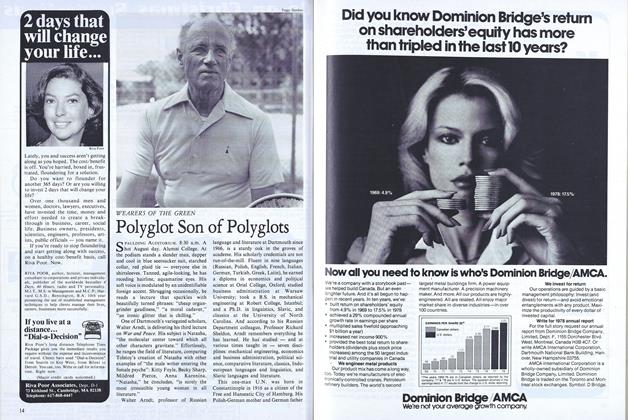

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1979 By JEFF IMMELT