"The rich are different from us," said F. Scott Fitzgerald."Yes," replied Ernest Hemingway, "they have more money."Like foundations, people come with pocketbooks of varyingdimensions, from fattest to slimmest. But the capacity is finiteand the need infinite. Like foundations - and the rest of us - the rich must make choices.

FORTUNE smiled on him from the start, but imagination, skill, and hard work have compounded the rewards. In the understated euphemism of the well-bred, he would be known as "very comfortably off."

While he accepts his status as the natural outcome of the economic system, diligence, integrity, and one generation's looking to the needs of the next and the next and the next, he is keenly conscious of the obligations attendant upon his affluence. So is his wife, who was nurtured in the same tradition.

They measure the casual appeals in bulk, not numbers. "We get about half a bushel a year through the mail," he says. "Oh, no," she argues, "more than that. It's probably nearer a bushel. Some days, the stack is three inches high."

Once they dealt with them piecemeal, until they discovered that they were responding to duplicate appeals. "We were getting hit more than once by the same outfits." So now, aside from a few answered at traditional times,, they all go into one large basket, accumulated till the end of the year. Then, some quiet evening, they take the whole lot upstairs, spread them out on the big bed, throw away extra copies, and decide what to give to whom. "Obviously, we can't give to everything, but we do our best. And we look very hard at new things."

"I give a lot to ASH," she says, smiling broadly. "Once I threatened to give $100 a day until he quit." He laughs. "Very effective! I haven't smoked a cigarette since."

The deluge at the office is even heavier - political fundraisers, testimonial dinners for professional associates at $50 to $1,000 a plate; clients' pet philanthropies; dire warnings of threats to the American way of life if this or that person does or does not get elected, if this or that piece of legislation does or does not get passed.

"The office takes care of appeals in the local area; the others we shove back to branch managers to handle. They're not on strict budgets - they have some flexibility - but they have a rough idea how far they can go."

"We really get behind local causes," he says. He's on both sides of that fence. As a trustee of one institution or another, "I get to hit the heavy-duty prospects. I'm pretty practiced at applying the velvet glove." His wife "is a good back-up with the one-two punch," he says admiringly. "She's a real barracuda of a fund-raiser. She never lets go."

He's sophisticated enough to know what's expected when he's approached to help out with a campaign: "You make your own best effort first, then get going on your committee." He is working hard for the Campaign for Dartmouth - after budgeting his own pledge carefully in the light of other ongoing obligations. He was relieved not to be assigned any alumnus whom he had recently solicited for generous contributions to a local capital drive. "He might still be smarting from the last campaign I hit him on."

He gives Dartmouth high marks for fund-raising conduct. He doesn't object to the appeal to nostalgia and sentiment. "It's very effective under certain circumstances, in large gatherings when everyone has had a few drinks and camaraderie is running high." But, in small meetings or with initial contracts, he respects the straightforward approach. "They talk purpose, explain targets, outline needs - no hard sell."

He practices what he preaches. "I've never liked the idea of playing it coy. I want to know what it's about. You don't ask someone to lunch or to dinner or to a meeting without laying it on the line beforehand. I dislike high pressure, and I will not use it. I will never, never go along with the 'We've got you down for "X" dollars' approach. I don't know what someone else's problems are, how many relatives he's supporting, how his business is going." When a local appeal comes his way, "I want to know how much they're trying to raise. Then I can figure my fair share."

They keep no rigid budget for giving, these two, nor do they tithe in the strict sense of the word. Their philosophy is based on the responsibility that is the concomitant of a healthy endowment of worldly goods. "We give according to what we think is a reasonable stewardship." Their priorities are on community services and education. "Our heaviest personal support - the major giving - goes to our church, the hospital, the 'Y' and prep schools and colleges, four of each," he says.

"But Dartmouth," she says pointedly, "gets the most."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

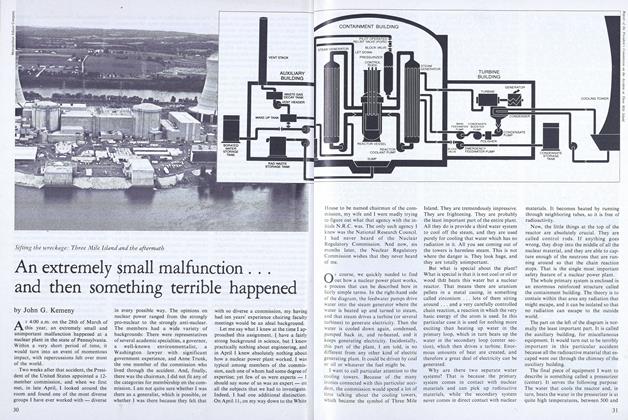

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

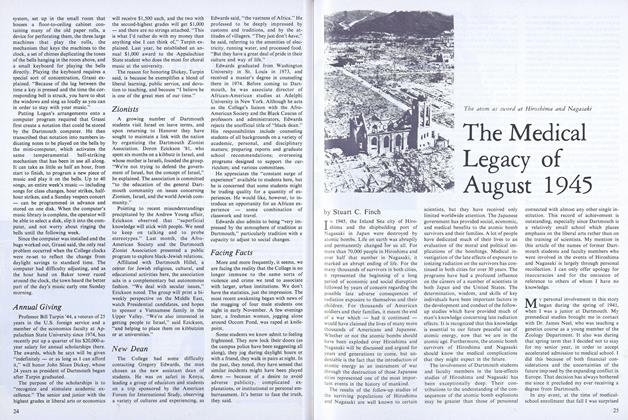

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R. -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80