Foundations and philanthropoids

"THE Ford Foundation ... is a large body of money completely surrounded by people who want some," wrote Dwight Macdonald in his 1956 study of that veritable ocean of funds in search of deserving supplicants.

Undeniably the giant of them all, Ford is still only one of some 26,000 such instruments of organized philanthropy, the overwhelming majority of them comparative puddles and ponds. Established as a vehicle to avoid dismantling the Ford Motor Company to pay the taxes that might otherwise have been levied on the estate of old Henry Ford, a decade ago it held assets of $3.7 billion.

Foundations are by no means uniquely American - in one form or another, they date back to the ancient world - but they are peculiarly suited to this nation of willing workers and more or less willing givers, of worthy causes and non-profit institutions dependent on private financial support. The great fortunes accumulated in the wide-open laissez-faire economy of 19th and early 20th-century America are reflected in the names of the great foundations of today: Mellon, Carnegie, Rockefeller, Astor, Ford. Whether the old tycoons or their descendants acted out of guilt or genuine good will matters not one whit to the thousands of colleges, libraries, hospitals, churches, and service agencies that are their latter-day beneficiaries.

These funds come in all sizes, shapes, models, and purposes, from the three - Lilly and Robert Wood Johnson, together with Ford - capitalized at over one billion dollars to almost 16,000 that have assets of under $100,000. Ten per cent of them account for 80 per cent of all foundation giving; most of the other 90 per cent have been described as mechanisms devised to promote the enlightened self-interest of the donors. Some have narrowly specific objectives; others, broader though still defined fields of interest. The $2.16 billion they distributed last year may be dwarfed by the $32.8 billion in individual largesse, but the sum is nonetheless significant - to a sinister degree, some claim - in the national life.

Though no strangers to strident criticism, often from opposing ideological factions simultaneously, private foundations had until about ten years ago operated in a manner relatively unhampered by government regulation. The Left had long claimed that they were invented by the rich and the powerful for the sole purpose of maintaining the status quo, and their wealth and privileges along with it. The Right had charged that they were manipulated by rich liberals out to bring down the free-enterprise system and the Republic with it. Both alleged undue influence on the political process. Evidence substantiated cases of corruption and abuse, particularly among the smaller foundations. The almost casual admission at 1969 Congressional hearings by John D. Rockefeller 111, whose personal lifetime philanthropy has been estimated at $93 million, that he had paid no income taxes since 1961 stunned both the Congress and the nation. The results, called corrective by some, over-corrective by others, have been reflected in a variety of tax reform legislation in the intervening years. Donors are now limited in the percentage of income they may put into tax-exempt foundations. Other requirements are that private foundations pay out either their entire annual income or five per cent of their assets, whichever is larger; that they pay each year an excise tax of two per cent (recently reduced from four) of their net investment income; that potential conflict-of-interest on the part of trustees and professional staff be closely monitored; and that their affairs be part of the public record. Meanwhile, the irony of taxing a taxexempt institution for the purpose of justifying its tax-exemption has not escaped notice.

The new tax laws not only led to public scrutiny, but they set off a tidal wave of almost fretful narcissism worthy of a conscious-raising encounter group. Since 1969, organized philanthropy has spent a remarkable amount of time and money examining its own navel. Breasts have been extensively beaten, mea culpas loudly cried. Great foundations have financed exhaustive critical studies of their counterparts and paid for reproducing annual accountings of their brethren, that all may read and know.

Institutionalized philanthropy in the form of foundations is big business, with assets in an uncertain stock market of $35.3 billion, the income from more than one fourth of which flows into education. It has nurtured a whole new breed of professionals: fund-raisers on the one hand, foundation executives on the other, devoted respectively to the getting and giving of funds. Grant-writers' manuals enjoy a brisk market; grant-writing workshops, university-sponsored, instruct the novices and hone the skills of the experienced in the fine art of not being among the 80 to 90 per cent of applicants whose proposals are rejected by foundations, corporations, and government agencies.

CLOSE to 200 Dartmouth alumni, including three trustees, are actively involved with foundations, as either executives or donors. W. H. (Ping) Ferry '32, former vice president of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, later was the executive officer of the anti-Establishment DJB Foundation.until it put itself out of business in 1974, according to an accelerated self-liquidating plan, by disbursing capital along with income. John W. Huck '38 is a veteran of both camps: after ten years as director of medical development for the University of Chicago, he was an independent consultant for five and now divides his time between the Oscar Mayer Foundation and the affairs of the Associated Colleges of Illinois. Robert N. Kreidler '51, a self-styled member of the genus philanthropoid, is executive vice-president of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

The organizations they serve or finance are as different as their passions, their purposes, and their politics. What they have in common are the tough decisions as to how private funds should be put to public use in the most effective manner, consistent with the principles of donors or trustees. Like individuals, foundations vary enormously in their assets and their incomes. But no matter how large the supply of money to be disbursed, it is exceeded always by the demands upon it. In the world of philanthropy, the irresistible force of limitless need daily confronts the immovable object of limited funds.

The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, established in 1934 by the late chairman of General Motors and personally - and autocratically - directed by him until his death in 1966 at the age of 90, is one of the giants, with current assets in the neighborhood of $275 million, down from a 1968 peak of $360 million, and annual disbursements running about $15 million. It was set up "to concentrate to an important degree on a single objective, i.e., the promotion of a wider knowledge of basic economic truths" - for which most observers read "opposition to Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal." Robert Kreidler joined Sloan as director of educational af- fairs in 1962, after serving in the White House as an adviser on science and technology, under both President Eisenhower and President Kennedy. Alfred Sloan was still operating his foundation "in terms of his own interest" as chairman and chief operating officer. "It was a very different place then," Kreidler recalls.

Like most large foundations, Sloan concentrates its grants in certain program areas - in this case, science and technology, economic research, management education, and medical research in the very limited sense of cancer study, exclusively through the Sloan-Kettering Institute and the complex of which it is a part. The donor's principal interests have remained the foundation's since his death, although the areas within the fields have been broadened. Where, for instance, Sloan once made grants rather narrowly in engineering, it is now interested in the social consequences of engineering practices, Kreidler explains. Similarly, management education has broadened into concern for management in the public sector as well, which led to a $150,000, one-year grant to Dartmouth to help the College develop courses for ,the new undergraduate major in policy studies.

"Where higher education per se is not one of our areas of principal program interest," Kreidler says, "colleges and universities are the principal agents for the use of Sloan Foundation funds. About 80 per cent of our income flows to institutions of higher education."

Sloan receives well over 1,000 serious proposals in a year's time, aside from the literally thousands more, in areas outside its program concerns, that are promptly acknowledged and politely declined. Between 70 and 80 "major grants, in sixdigit figures," are made per year. In addition, some 80 Sloan Fellowships for basic research - prestigious grants to individual young scientists, given not on the basis of application, but only on recommendation of eminent senior scientists, department heads, and former Sloan Fellows - are awarded each year. Another $850,000 in smaller grants brought 1978 funding to about $13.5 million.

The Oscar Mayer Foundation, for which Huck is the entire professional staff, on a part-time basis, has a very different function. Sponsored by the Oscar Mayer Company, it had a pool of assets of about $3 million at the close of 1978, a year in which its grants totaled slightly under $900,000. It was established, Huck says, to contribute to institutions and services of benefit to the corporation's employees and the communities in which they do business. "There's a great variety in the grants we make," he reports, "from Little League teams to private colleges in states where we have major plants. About 15 per cent goes to projects aimed at improving the quality of life in the inner city, in Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, for instance."

The Mayer foundation receives about 100 to 150 serious proposals a month, half of which Huck declines personally, the other half going on the trustees' regular agenda. Of the latter, he says, "We give to an average of 40 per cent - about 10 per cent of what they've asked for." The analogy with organizations set up to promote the general welfare is very tenuous, Huck warns. "You must draw a very heavy, thick line between the corporate foundation and the family foundation. We are spending stockholders' money, and stockholders do not invest in Oscar Mayer to do good works."

The DJB Foundation, now defunct, was as radically different from either Sloan or the Oscar Mayer Foundation as Ping Ferry is from the average Dartmouth alumnus. Daniel J. Bernstein, in the words of his foundation's final report, "had inherited more money from his father than he knew how to cope with." Wanting to be generous, but not knowing "how to give away intelligently each year as much money as the tax laws encouraged," he set up the foundation in 1948 "as a holding operation until he had sorted out in his mind what needed to be done.' Meanwhile, he kept on making money in the stock market; upon his death in 1970, almost $6 million more went into the foundation. In keeping with Daniel Bernstein's conclusion that "the chief enemy of mankind was not famine, flood, or disease, but quite directly the injustice of governments in general and of the United States in particular," the trustees, who included both Ferry and Bernstein's widow, continued the foundation's move "away from usual objects of philanthropic attention toward the victims of what seem to us increasingly to be official malevolence and indifference." Its grants gravitated "toward ghettos and barrios in the city and toward neglected communities in rural areas."

Aware that conventional wisdom is that "there's something un-American about spending capital," Ferry says that after Bernstein's death the trustees decided, in the tradition of the Julius Rosenwald Foundation and others, to devote principal as well as income to the cause. They determined first to use up the capital in ten years, a schedule later accelerated to four. "The needs are now," Ferry explains, "and who knows what will happen in ten years. A sense of eternal life promotes a different view of what philanthropy means. If a foundation is set up to go on and on and on, it gets interested in the wrong things - return on principal, judgment of posterity, opinion of the neighbors." "It's a matter of temperament," Bernstein's widow adds. "I have little sense of the future, none of posterity."

Ferry finds "the whole business of giving away money very boring.]' Cautioning - probably unnecessarily - against a view of DJB as typical, he suggests, too, that "the whole way a standard foundation works is very boring. It's an ego trip for grantors who like to see a college president crawl."

WHILE the DJB trustees were accelerating the dissolution of capital, others with a different view of the future have been gravely concerned with the erosion of assets, caused by the withering impact of a faltering stock market, inflation, and tax laws. "Where our capital reached an all-time high of $360 million in 1968, it currently stands at $275 million," Kreidler reports. At the same time, mindful of soaring program costs to colleges and universities, exacerbated by severe curtailment of government funds, Sloan has tried to maintain the grant level of a decade ago. "We're giving at the same dollar level and getting half the results, where we should actually be doubling the grants." In order to avoid cutting grants as assets have shrunk in value and income has fluctuated, the foundation has used substantial amounts of capital. "And since the 1969 legislation requires that we pay out all our income or five per cent of our capital each year," he laments, "we have no way of restoring capital." Although Kreidler favored the tax-reform legislation in principle, testified for it at Congressional hearings, he differs strenuously with the subsequent implementation. "The principle is correct," he declares. "Foundations should not be in the business of accumulating money. Our business is to spend money. But the payout requirement should be related to a sound judgment of what is a reasonable rate of return. We should not be required to pay out more than a reasonable return on our assets - unless the purpose of the pay-out is to abolish foundations. This way, it's just slow erosion."

Kreidler sees the excise tax in a similar light. Before tax reform, he explains, foundations were not adequately monitored or audited, since as tax-exempt institutions, they were not revenue-producing. "The purpose of the tax I couldn't argue with," he says. "We should be audited. In fact, I proposed that foundations be assessed a fee for the cost of the strictest kind of government auditing surveillance. But, while Sloan pays its auditors $25,000 a year, we pay a tax of half a million - and I know it doesn't cost the government half a million dollars to audit the Sloan Foundation. Again, the principle was fine, but suddenly it was producing $70 to $80 million a year for the federal treasury that should have gone to institutions like Dartmouth or to cancer research."

Huck, too, finds the federal hand resting heavy on the private foundation, and the corporate foundation caught in the middle between the stockholders and the government. "It's ridiculous," he says. "The first question Internal Revenue asks is whether a grant we have made has any relation to the interests of the company. The foundation can't do anything on behalf of the company, according to Internal Revenue, but on the other hand, we have to justify grants to the stockholders in terms of benefits." Between the excise tax and onerous reporting requirements, the company is considering dissolving the foundation, Huck says. "All it would mean is that we would use a different checkbook for contributions."

CONTROVERSY over control of the proposed center for Middle East studies at the University of Southern California by a group of American businessmen trading extensively in the Middle East has focused new light on the old question of the impact of grants on education and society. The Ford Foundation's support of voter registration drives in the South during the sixties brought charges of tampering with the political process. Seed money for new academic programs is said to influence curricula and, hence, the intellectual and social direction of the young. Strings are intrinsic to all grants, some claim, thereby affecting priorities and altering perspectives.

Most foundation people agree that their money has inherent impact, although they think it has been exaggerated. Although Ferry acknowledges that most recipients would prefer that "we just stuck the money under the door in a plain package," he considers stipulations natural and "perfectly decent and moral. The donor should be able to decide on a good vehicle to carry out a certain principle." On the other hand, he adds, "The whole relationship is rife with deplorable possibilities. The situation with USC is just a rank growth."

Kreidler agrees that foundations maintain a certain leverage through their grants, particularly on education. "When we make a major grant to an institution for a specific program, it is for a limited time. If it is to have any influence - and we hope it will - it will have to be funded later on by the federal government or by somebody else or by the institution itself. We should have extraordinary influence if we are doing our job properly, but it should be an influence welcomed by the institution."

"Elitism" is a charge Kreidler cheerfully accepts. DJB's concentration on the powerless seems an anomaly, most foundation funds flowing into Establishment institutions. "We're an investment company; we invest in people," says Kreidler. "Most crucial in winning approval of a grant is our judgment of the competence, the imagination of the individuals who will do the job. Our principle criterion is the quality of the people, and, of course, it's the quality of the people that makes the quality of the institution."

ASSESSING the quality of a proposal and the personnel who will carry it out is a long and careful procedure at the Sloan Foundation. When a grant application appropriate to Sloan's program interests comes in, either Kreidler or the foundation's president assigns it to one of ten staff officers, who have the authority to decline it following personal review - a fate that meets about half of the 1,000 serious proposals Sloan receives in a year. "If the staff officer wants to go on or isn't sure whether the proposal should be declined, it is circulated to all officers with a comment sheet," Kreidler explains. "It then goes on the weekly agenda automatically. The staff officer, by then knowing what the questions and the doubts are, can again at that point decline it, or send it out for review." If the review is favorable, the staff officer in charge recommends that it be put on the agenda for the trustees, "a hard-working unpaid board" numbering 17 at full strength. The staff officer then takes on the role of advocate, becoming in a sense a colleague of the petitioner, arguing for the approval of the grant. "When I write a memo in support of a grant," Kreidler declares, "it contains much more than the applicant has told me - how. it fits our program, for instance, or why it is the best use of our resources. We don't commit the crime, but we have to prepare the defense."

DARTMOUTH has over the years done very well with grants from the Sloan Foundation - by Kreidler's definition a certain testimony to the quality of the College. When he was solicited for a 25th reunion gift by a classmate, Kreidler decided to ask the Sloan computer just how well. "I've given at the office," he jocularly told the solicitor for the class of 1951 - $8 million worth.

There is disagreement among professional personnel as to whether Dartmouth connections in foundation executive offices or on their boards are a help or a hindrance to the College's cause. Trustees tend to bend over backward to avoid using their influence; foundation officers usually disqualify themselves from participating in any Dartmouth proposal. On the other hand, J. Ernest Nunnally, director of foundation and corporate relations at the College, says that it can be helpful to have an alumni contact, in the sense of getting a clearer idea of the right approach. The benefit is greatest, he adds, in the case of small family foundations without professional staff.

Dartmouth gets a fairly small piece of the foundation pie overall - only $2.8 million during the last fiscal year. The eight Ivies, plus M.I.T. and Stanford, the group with which the College is generally compared in such matters, received a total of $101.6 million in foundation money, or close to 25 per cent of the funds received from all sources of voluntary support. While less than eight per cent of the $36.8 million Dartmouth received last year in private funds came from foundation grants, Stanford got about one third of its $64.5 million from foundations and Harvard almost one fourth of its $70 million in voluntary support.

As Addison L. Winship '42, vice president for development and alumni affairs, explains it, the answer is in the company we keep. While the College is classified as a private university because of the three associated schools, its heavy concentration on undergraduate programs and comparatively small graduate-school enrollment pretty much invalidate analogies with Stanford, or most of the other Ivies. "We're neither fish nor fowl," Winship points out. "We show up very well compared with undergraduate colleges." It is research programs, phenomena primarily of professional schools rather than undergraduate teaching institutions, that constitute the big drawing cards for foundation grants, he adds.

If the overall sum Dartmouth realizes from foundations pales before the largesse bestowed on her sister institutions, the success rate of the College's proposals is exemplary. Where, on national average, five to ten per cent of all proposals hit pay dirt, half of those that Dartmouth proposed received funding last year, Nunnally reports. Nunnally, who has been raising money for places and causes he believes in since his undergraduate days at Dillard University, attributes Dartmouth's batting average to careful homework and the quality of the institution and its teaching personnel. "It's a people business," he says, reiterating Kreidler's viewpoint. "People give to people, not causes."

Research into the complex, multifaceted, changing world of foundations must be constant, if the development officer is to know what proposal for what sort of project of what magnitude should be directed to what foundation. Annual reports, trade journals, and news stories that indicate special interests or changing emphases are required reading; economic bellwethers and tax legislation must be monitored closely, along with developments in the academic world. "You have to keep on top of it all," Nunnally emphasizes. "The major foundations have special program interests which remain fairly constant, but the medium-sized ones are more likely to experience radical shifts. One, for instance, recently changed its concentration within a year's time from medicine to communications, primarily in the area of public broadcasting. What would have been appropriate one year would have been fruitless the next." "Knowing your stuff," he went on, "means knowing that Ford or Sloan likes pilot programs, but wants to know how you're going to float after the program is over; it means knowing whom to take with you - people from student affairs, the sciences, social sciences, or whatever; when to involve the president; how to supply good data."

Nunnally works closely with Gregory S. Prince, associate dean of the faculty, in making and presenting proposals, bringing up the heavy artillery in the form of top College officers where warranted. President Kemeny is involved in some four or five major solicitations a year - "when we're going for seven figures, or half a million or more," Nunnally says. "We make sure, of course," he adds, "that we've done all the necessary groundwork beforehand. But presidents like talking to presidents."

THERE is a basic and fundamental difference in philosophy of financial support, Addison Winship declares, which is disturbing the symbiosis that exists between the private foundations established to promote the principles of their donors and the educational institutions deemed worthiest to help accomplish that task. "Most foundations restrict their grants to support of innovative, creative, imaginative new programs, while most colleges need money to pay their bills."

The glory days of the unrestricted grant peaked in December 1955, when the Ford Foundation announced an immense disbursement of $550 million, more than two million of it Dartmouth's share. Ironically, it didn't matter so much, Winship says, "during the boom and growth period between 1945 and 1970. But now, in times of austerity for them and for us, when we have to tighten our belts, we need the unrestricted bread-and-butter money a lot more than we need new programs that will have to be supported from other sources after the original grant has run out."

Kreidler concedes that "In fact, foundation money is very costly to institutions. We help start new programs; they hire tenured professors; they're stuck with the thing. We say from the start that we're not going to support the program forever. . . . In my first dialogue with a college president, I ask 'What plans have you for coping with programs we help create, when we're not there to sustain them?' "

"Like most large foundations," he goes on to say, "we don't give grants for endowment, for buildings, for facilities" - with only occasional exceptions where, for instance, certain facilities are essential for the performance of certain programs. "We don't give to capital campaigns per se. . . . Our motivation is this: We don't give a grant to Dartmouth because they have a Campaign for Dartmouth going; we give a grant to Dartmouth because of a program and the people who are going to carry it out. Such grants may include support of programs of basic importance to the institution. We are not solely interested in new programs; we are also interested in revitalizing established concerns."

President Kemeny has challenged the prevailing philosophy of foundations, arguing his position on the basis of the very survival of many institutions of private higher education in the United States in the critical years ahead. While "I am not opposed to supporting 'add-ons' that improve the quality of education . . .he wrote the president of one foundation as long ago as 1974, "I feel that the policy of supporting only 'add-ons" will lead to a worsening of our financial situation." In a speech to an educational fund-raising group in 1977, he warned that "the major foundations have an absolute mania that they will give you money not for ongoing programs, but only for new programs .. . for which after a short interval, "the institution has to assume support, usually indefinitely."

"I have talked to the presidents of a couple of the major foundations," Kemeny said, "and have tried to convince them that they may be very successful in putting higher education out of business if they continue that policy. So far I have had very little impact."

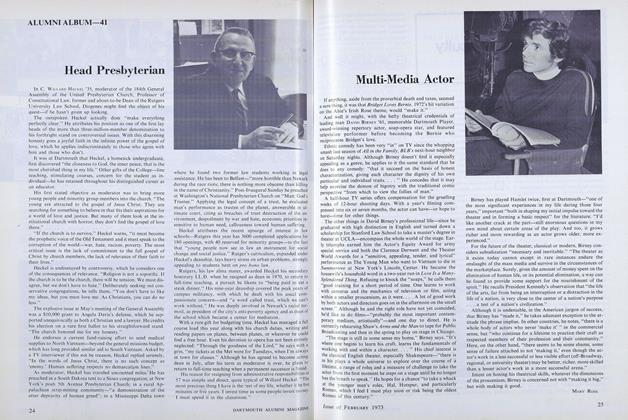

John D. Rockefeller, founder of the familyfortune, was known for a very personalbrand of philanthropy, distributing dimesto golf caddies and such. His son, John D.Jr., had a different style, giving the firstmillion toward Hopkins Center, whichgrandson Nelson '3O (opposite, with PresidentJohn Dickey) dedicated in 1962.

Sloan's Robert Kreidler '5l: "We're an investment company; we invest in people."

W. H. Ferry '32, helping DJB self-destruct: "Giving away money is very boring."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

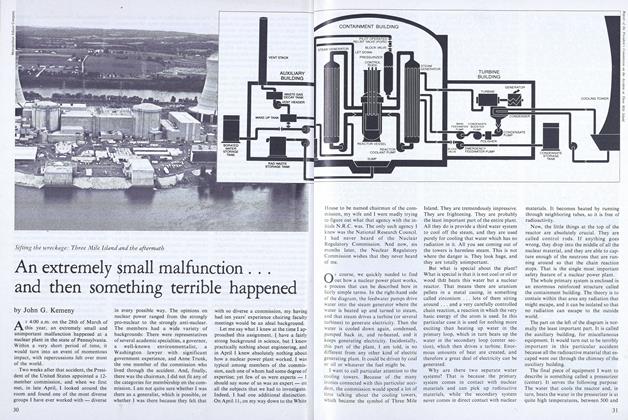

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R. -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

December 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE

Mary Ross

-

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

APRIL 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

DECEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleMulti-Media Actor

FEBRUARY 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureLiberal Arts, yes 'Core of Knowledge,' no Changing the Calendar, maybe

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleSharing Faith and Fear

MAY 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

Article"To the conquest of the unknown and the advancement of knowledge."

MARCH 1984 By Mary Ross

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1971 By B.B. -

Feature

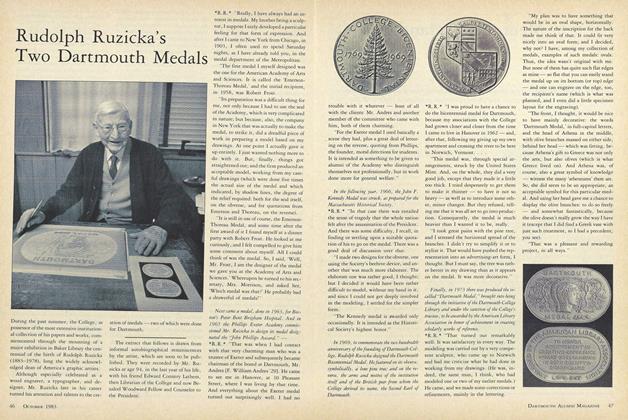

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

OCTOBER, 1908 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureParents Committee Report

December 1960 By Guilford. Hartley -

Feature

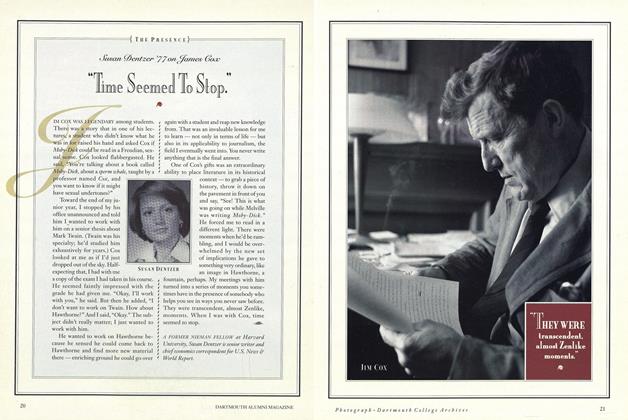

FeatureSusan Dentzer '77 on James Cox

NOVEMBER 1991 By Jim Cox -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Mar/Apr 2006 By Paul Stone '60 -

Feature

Feature1958 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

DECEMBER 1958 By William G. Morton '28