The biological effects of radiation impose the most stringent conditions, and thosewho are inclined to rejoice in the coming ofatomic power for peaceful purposes, alongwith those who minimize the dangers ofatomic warfare, should at least understandthese conditions. - No Place To Hide, February 1949

DR. David Bradley's third floor office, Tuck School of Business Administration. A file cabinet in one corner, his desk in another. Above his desk, a map of the High Sierras. To the left of the map, a large, framed photograph of the Edward Winslow, a six-masted schooner used early in the century to carry coal. On the opposite wall, above his bookshelf, a navigational map of the waters along the Maine Coast and a small picture of a 53 year-old sailboat that his family has owned since 1942. He points to the picture, puffs on his pipe, and says with a slight smile and a note of sarcasm, "As you can see, we're not very old fashioned."

Bradley claims an affinity for the physical world:. "If it isn't the mountains, it's the ocean - I've got to be near one of those two." His wall hangings tell something about his youth in Wisconsin and time spent in the Sierras, about his grandfather who was a founder of the Sierra Club and a friend of John Muir the nature writer, about his interest in sailing ships and holidays on the coast of Maine. But if they in some way imply that Bradley is old-fashioned, that's only half the true story.

A National Geographic article about ski-jumping at Dartmouth lured Bradley to Hanover in the fall of '34. He became an all-America ski-jumper, joined the now defunct Phi Gamma Delta fraternity, majored in English, and lived his junior and senior years in Crosby Hall with his brother Stephen '39 and Everett Wood '38. Bradley still goes alpine skiing, but not often: "I don't like crowds, I don't like waiting in lines, and I don't like machinery." He prefers cross-country skiing in the open pastures and hills "somewhere between Woodstock and Hanover." Bradley had it in mind when he entered Dartmouth to become an opera singer or a doctor. He went on to graduate from Harvard Medical School, and says that he still sings "for my own enjoyment - nobody else's." But what is a trained surgeon doing with a third-floor office and a position as Senior Lecturer in Effective Writing and Speaking at a graduate school of business administration?

As a doctor with the Army, Bradley witnessed, from the window of a Navy PBM-5, the two atomic bomb explosions in 1946 at Bikini Atoll. In his own words, "You don't go through a close association with a couple of atomic explosions and come out the same person you went in - I didn't anyway." Discharged from the Army, he became a surgical resident, and began writing his best-selling book, NoPlace To Hide, about the costs and dangers of atomic power. Much of the material for the book came from letters written to his wife Elisabeth during his time at Bikini. E. B. White later commented, "The most sensitive instrument at Bikini was Dr. Bradley's pen."

Bradley was also active at that time in the United World Federalists' movement for world government. He noted President Kemeny's participation in that cause: "We were both smitten by the same fantasy that you could govern this world by a single government." Bradley became preoccupied with John Hersey's Hiroshima, with his own personal observations at Bikini, with his knowledge about atomic energy, with the prospect of treating countless burn patients should there ever be an atomic war, which he described as a kind of insanity. He became occupied with these concerns "in a way that made it difficult to practice medicine, and in medicine you're responsible for people's lives - you don't want to be careless and make foolish mistakes." He gave up the practice of medicine in 1950. "Let's say I was an early mutation; I mutated from medicine into writing." A filmed version of No Place ToHide was in production when on September 23, 1949, American intelligence sources detected that the Russians had exploded an atomic bomb. For security reasons, production of the film was stopped.

Many of the effects of an atomic explosion that Bradley could only guess about in the late forties when he wrote No Place ToHide have been confirmed by later, more detailed studies on the long-term effects of exposure to radiation and the problem of radiation being passed through the food chain. He credited his medical education for providing him with the analytical skills needed to make such accurate predictions. "You probably want to know," he asked, "if I go back on anything I said in that book. Well, the answer is no. For a long time I hoped that the fantasy of easy power might be available through that source, but it isn't going to be easy, it isn't going to be cheap, and it will never be safe."

Bradley has carefully followed the fate of the 160 Marshallese displaced from Bikini to Rongerik, an inferior island, just before the atomic testing. He said that it was decided about 20 to 25 years ago that it was safe for the people to move back to Bikini. But when an interest arose in the dangers of low-level radiation, new studies determined that the dust in the air at Bikini still contained extremely dangerous levels of radioactivity. So the atoll has been abandoned again. "The islanders are the latest victims of brainless technological movement," said Bradley. "We had a legal right to kick them off the island - we had no moral right. If Mexico had wanted to test a bomb on Martha's Vineyard, would we have allowed it? I think not."

Bradley commented about recent protests against nuclear power such as one at Seabrook, New Hampshire. "How do you make a protest? Have you ever thought about it? Suppose you honestly felt that the building of that power plant would jeopardize Boston? Suppose you were a Bostonian who felt that his children might be deformed because of it? Would you do anything about it? And if you did decide to do something, what would you do?" Finishing his string of rhetorical questions, he lamented the violence that often surrounds protests like the one at Seabrook, but he added, "The protesters are not at war with the police. Their aim is to make the issue more vivid, to get it into the consciousness of the people. I haven't engaged in protests, but I should have."

Since his mutation from medicine to writing, Bradley has produced five books, including a recent collaboration on Robert Frost and his poetry (reviewed in this issue). He taught at Kimball Union Academy before accepting the position at Tuck School 13 years ago. He hopes to help his students become skillful with words because he perceives a close association between words and actions: "Words represent analysis which leads to decisions which foster actions. It's hard to be a writer. I'm not good enough to be a professional writer. It's extremely hard to sit there with an empty piece of paper looking at you - what the hell is there to say?"

Bradley and his wife settled in Hanover in 1952, first in a house on Allen Street, but they have lived for many years now in a large house on Occom Ridge. Bradley joked about settling in New Hampshire: "I married a New Hampshire gal, one of the McLanes, and they refuse to move. They won't leave New Hampshire. Besides, I can't think of a better place to live. Although I could live happily in many, many places." Bradley has six children ranging in ages from 36 to 20. All the children are out of the house now, and "it's a change," says Bradley, "but not altogether a bad change." Owing to the large number of visitors and extended house guests who have stayed with the Bradleys over the years, the house on Occom Ridge has been nicknamed the "softtouch motel."

Bradley's activity in community affairs has led him as far as a seat in the New Hampshire House of Representatives. He has no plans for any future political activity. "There's a lot less I'll attempt to do now," he says, "unless I can see some clear purpose, or meaning, or action that could come out of that involvement. For instance, I used to read all sorts of newspapers, magazines, and newsletters - it never came to anything." If at times Bradley puts on a gruff exterior and plays the role of cynic, people who know him well say this is to protect his core of idealism. As one close friend said, "He's seen a lot of good causes go down the drain."

Bradley recently spoke about the New England origins of Robert Frost's poetry to two dozen people in Hanover's Howe Library. He sat on the edge of a large table, dressed in a tweed jacket, white shirt, dark tie. He conjured up images of country scenes, settings, personalities, accenting them with sensitive readings of some Frost poems. He spoke about writing, and he related anecdotes about his collaboration with Dewitt Jones '65 on Robert Frost: ATribute to the Source. It seems that Jones used to date Bradley's daughter, which gave the father more to worry about than just trying to condense his manuscript, which he revised five or six times.

Many of the two dozen listeners had known Frost or members of Frost's family intimately, and Bradley asked them to share their memories and impressions. One older woman, Esther Grover, painted an impressionistic portrait in words of Frost's daughter, Irma Frost Cone, and his grandson. Others chimed in, retelling their well-worn stories to create a collage of Frost folklore. Bradley ended the evening gracefully, lit up his pipe, mingled with the crowd. He was among friends, and he showed nothing of the cynic then.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

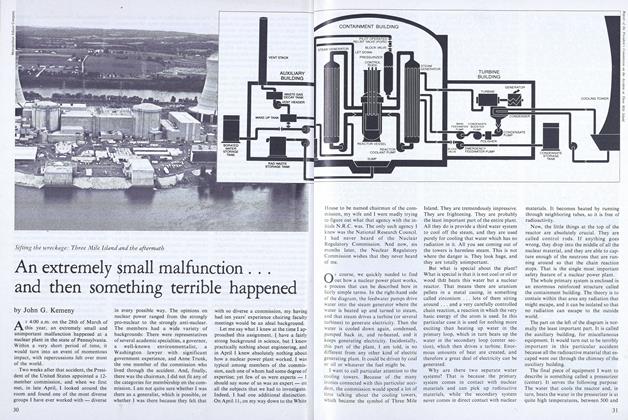

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

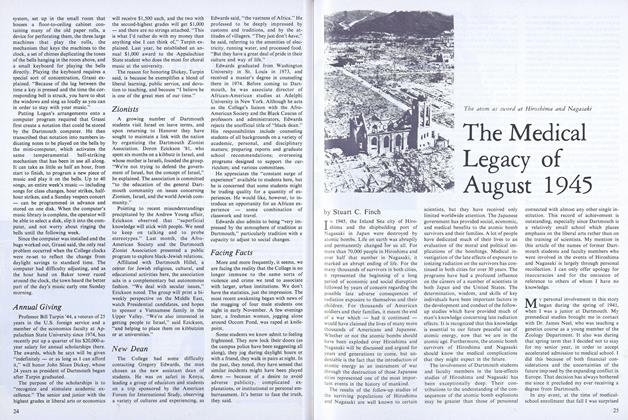

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R. -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

December 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE

MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Beth Ann Baron '80, Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Bard's American Friend

September 1979 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleZombie of the 1902 Room

October 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Great Society

April 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Books

BooksExperiential Education

OCTOBER 1981 By Michael Colacchio '80