For the past 50 years, the bells in the Baker Library tower have been controlled by three intricate machines similar in mechanical principle to the mechanisms that operate player pianos. Since September, the bells have been played by a computer. Drewry Logan, who has been busy since July rearranging the hundreds of songs stored on the old perforated paper rolls, explained the operation of the previous system - which is still functional - and reasons for the change.

When a roll with a musical score punched on it is fed onto one of the three custom-built machines, air forced through the holes switches on and off an electric current, which activates an electromagnet, which moves a piston, which strikes the inside of one of the 16 bells, which were all cast in 1929. The largest bell weighs three tons and has "vox CLAMANTIS IN DESERTO" stamped on it. The paper rolls, carefully perforated by hand, were getting fragile, Mrs. Logan said, and when Frances Zeller and Krista Jensen retired in July, after more than a quarter century of punching rolls and playing them on the machines, it seemed like a good time to act on Music Professor Jon Appleton's suggestion of using a computer to run the system.

Because the computer allows for more precise control over the bells, which have a range of an octave and a half above middle C (with four notes missing), Logan was able to arrange more intricate musical lines than were previously possible. And because of the way music is now stored on the computer, it is easier to select individual pieces appropriate to a special occasion. Many of the old arrangements have been reworked, and some tunes, popular in their day but now unfamiliar, have been weeded out of the repertoire of mostly folk songs and classics. "The Bach chorales are especially beautiful on the bells," Logan noted. She also said that some music, despite requests, cannot be played on the bells because of limitations imposed by the missing notes and a certain amount of recovery time that has to be allowed for between strikes. "If you really want to know how the new system works," Logan suggested, "climb up to the bell tower and talk to Paul Grassi, a senior who was hired to transcribe the sheet music onto a computer file. He's tremendously talented and dedicated, and seems to spend most of his time up there."

Grassi was most accommodating. He said he spends an average of ten hours a week working on the bells, although he spends considerably more time in the tower because he finds it a quiet place to study - except, of course, when the bells are ringing. He has a locally built minicomputer, specifically designed for electronic music systems, as well as a terminal connected to the Dartmouth computer system, set up in the small room that houses a floor-to-ceiling cabinet containing many of the old paper rolls, a device for perforating them, the three large machines that play the rolls, the mechanism that keys the machines to the clock, a set of chimes duplicating the tones of the bells hanging in the room above, and a small keyboard for playing the bells directly. Playing the keyboard requires a special sort of concentration, Grassi explained. "Because of the lag between the time a key is pressed and the time the corresponding bell is struck, you have to shut the windows and sing as loudly as you can in order to stay with your music."

Putting Logan's arrangements onto a computer program required that Grassi first create a notation that could be stored by the Dartmouth computer. He then transcribed that notation into numbers indicating notes to be played on the bells by the mini-computer, which activates the same temperamental bell-striking mechanism that has been in use all along. It can take as little as half an hour, from start to finish, to program a new piece of music and play it on the bells. Up to 40 songs, an entire week's music - including songs for class changes, hour strikes, halfhour strikes, and a Sunday vespers concert - can be programmed in advance and stored on one disk. When the computer's music library is complete, the operator will be able to select a disk, slip it into the computer, and not worry about ringing the bells until the following week.

Since the computer was installed and the bugs worked out, Grassi said, the only real problem occurred when the College clocks were re-set to reflect the change from daylight savings to standard time. The computer had difficulty adjusting, and as the hour hand on Baker tower raced around the clock, the town heard the better part of the day's music early one Sunday morning.

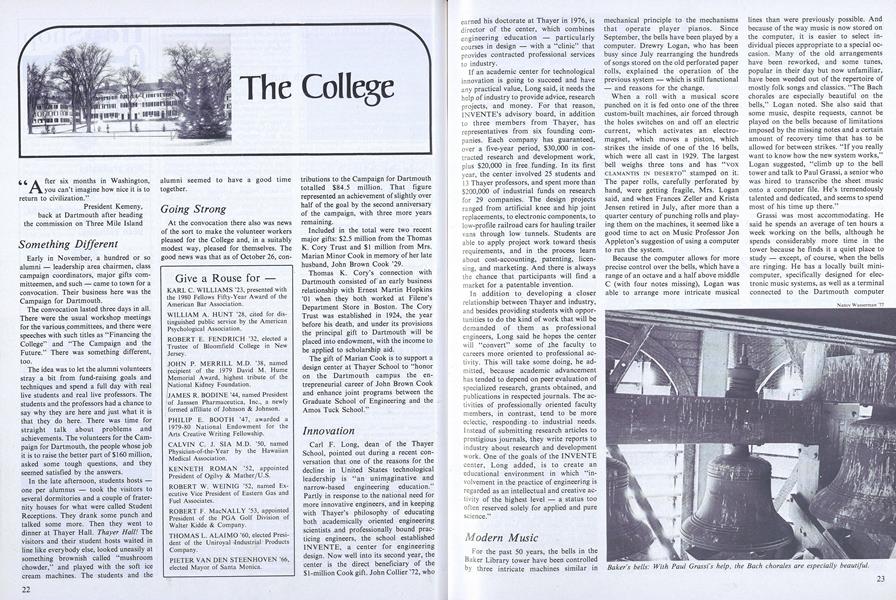

Baker's bells: With Paul Grassi's help, the Bach chorales are especially beautiful.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

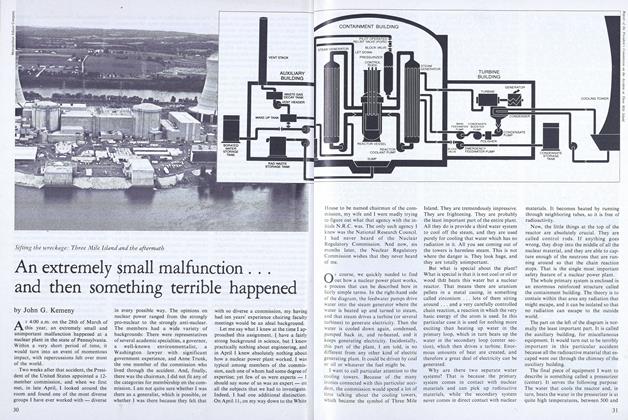

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

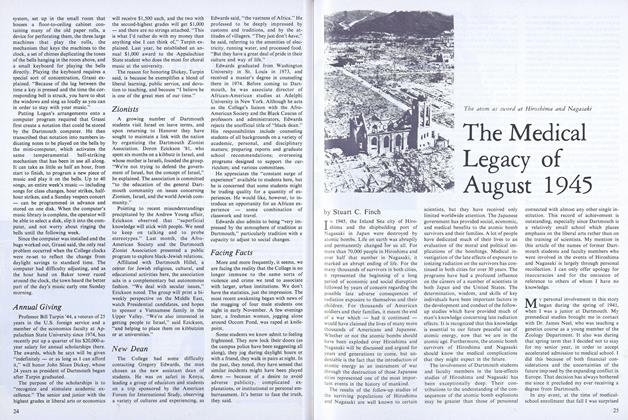

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R. -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80