God Is in the Details

The time has come to develop a new science-based worldview about the nature of God, one that bridges the schism between faith and reason, argues evolutionary biologist Stuart Kauffman ’61.

May/June 2009 ALEX NAZARYAN ’02The time has come to develop a new science-based worldview about the nature of God, one that bridges the schism between faith and reason, argues evolutionary biologist Stuart Kauffman ’61.

May/June 2009 ALEX NAZARYAN ’02THE TIME HAS COME TO DEVELOP a new science-based worldview ABOUT THE NATURE OF GOD, ONE THAT BRIDGES THE SCHISM BETWEEN FAITH AND REASON, ARGUES EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGIST STUART KAUFFMAN ’61

STUART KAUFFMAN HAS BEEN ON THE VANGUARD OF science for more than 40 years, but it does not take long for the philosophical young man who first arrived on the Dartmouth campus to show through. Talking from the University of Calgary, where he has been directing the Institute for Biocomplexity and Informatics for the last four years, Kauffman moves seamlessly from science to theology, a divide he attempts to bridge in the recently published Reinventing the Sacred: A New View of Science, Reason and Religion (Basic Books, 2008).

“shakespeare is just as important as einstein,” as Kauffman proclaims, isn’t an assertion one expects from a researcher known best for work in evolutionary biology. But then again Kauffman has always been possessed of a restless mind. As the title of his new work suggests, he believes a new understanding of divinity is necessary, one that embraces the tangible world and erases distinctions between faiths. He sounds increasingly impassioned as he describes his latest project, which declares the idea of a “supernatural god” obsolete and calls for an embrace of the “radical ceaseless creativity of the universe” that neither breeds fundamentalism nor fosters distinction between competing faiths.

Although an atheist, Kauffman comes across as deeply spiri- tual, thankfully free of the smug didacticism of recent nonbeliever authors such as Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion) and Christo- pher Hitchens (God Is Not Great). “the first central question about the origin of life is the onset of molecular reproduction,” writes Kauffman in Reinventing the Sacred. “when, and how, did molecules appear that were able to make copies of themselves?”

“i’m looking for an ethic to undergird the global civilization that is emerging as our traditions evolve together,” says Kauffman from his office in Calgary. The ethic, he believes, should be based on a shared appreciation of the natural world. Perhaps this search for universality is bred from a conviction—earned through a rig- orous study of the origins of life—that there are no easy answers and that any truth is heavily shaded by complexity.

early reviews of Reinventing the Sacred called it “ambitious and groundbreaking” and “provocative but difficult,” noting both Kauffman’s erudition and the book’s vast scope.

He arrived at Dartmouth, however, imagining a life in the arts, already having written what he calls “three bad plays” in high school. But by the end of his freshman year, with little to show from the stage, Kauffman knew the theater was not for him. Instead, he turned to the twin pursuits of philosophy and the outdoors that had enthralled New england transcendentalists such as emerson and thoreau a century earlier. “i loved dartmouth for the outdoors, for the intellectual climate, for the ease with which one could get to know the faculty,” says the avid skier. even now, after a career of working with Nobel Prize laureates and receiving more than a few accolades of his own, including a “genius grant” from the Mac- Arthur Foundation, Kauffman says his greatest honor was being named president of the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club.

After graduation he won a Marshall Scholarship to attend Oxford, where he made the leap from philosophy to medicine. “the trouble with philosophy is that you can spend an awful lot of time being clever but you don’t actually know you’re right,” says Kauffman with a chuckle.

Ironically, his forays into biology would take him to the brink of the existential uncertainty from which philosophy springs. Kauffman continued at the University of California at Berkeley, then earned his medical degree at the University of San Francisco. Focusing on the ability of genes to express their traits, especially through large aggregates known as gene networks, Kauffman began to realize how thoroughly our existence is based on the intricate dance between order and disorder.

His research suggested that genes do not work in an organized manner for the greatest good of the entire body. Instead, they exist forever on what he’s called “the edge of chaos,” and the proper functioning of a living organism depends on its self- organization and regulation, an arrangement that can often go awry, leading to genetic abnormality and disease. instead of the tidy model in which each trait corresponds to a single gene, Kauffman demonstrated just how complex gene interactions are—that health is just a moment of stability in a very uncertain cellular world. That early work captivated many researchers, including geneticist Jason Moore, who learned of Kauffman’s investigations as a graduate student at the University of Michigan in the 1970s. “His thinking about gene networks was inspiring,” says Moore, now director of dartmouth’s computational genetics laboratory and an avid proponent of Kauffman’s wide-scope vision of human genetics.

At the same time Kauffman understood that his research pointed beyond genetics. Like chaos theorists such as the late Ed-ward lorenz ’38 (of the famous butterfly-in-Brazil-causes-tornado-in-Texas model), he began to see complexity everywhere. Not only gene networks, but countless other systems—from social contracts such as a free-market economy to the delicate ecology of a rainforest—rely on the interaction between a multitude of elements that, while inherently given to disorder, are able to cooperate in ways that allow for periods of stability and productive collaboration. Think of paint coalescing, improbably but beautifully, into the tie-dye pattern on a T-shirt, and you have the essence of Kauffman’s insight.

In 1986 Kauffman joined the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), a think tank whose membership includes the Nobel laureate physicist Murray Gell-Mann and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Cormac McCarthy. At SFI thinkers investigate topics ranging from sexual violence during wartime to algorithms in quantum physics, the primary stipulation being fierce intellectual independence. “it’s one of the most extraordinary places in the world,” says Kauffman. “it is extremely exciting intellectually.” He spent the next 10 years (much of it under the auspices of his MacArthur fellowship) pioneering work in what he calls “adaptive complex systems,” trying to find the underlying laws that govern the ability of any system to organize itself into an orderly, working whole.

His investigations culminated in his 1995 book At Home in the Universe, whose groundbreaking thesis is that natural selection alone could not account for the richness of life. In it Kauffman claimed life initially sprang from the ability of enzymes to aggregate on their own according to the laws of complexity—“order for free,” he called it. darwin’s measured preference of one trait over another seemed far too timid for Kauffman. The universe was, instead, a noisy, cacophonous orchestra that somehow managed to produce beautiful music. There was something holy about this symphony. “i found myself hoping that there was a sacredness, a law—something natural and inevitable about us,” he wrote in At Home in the Universe.

Although criticism of Darwin did not sit well with some, many of Kauffman’s peers understood he was striking out in an exciting new direction. “darwin didn’t fill in all the details,” says simon Levin, a noted biologist at Princeton who chairs the science board at Santa Fe and praises Kauffman’s willingness to stand behind his ideas. levin explains that while darwin’s theories describe late-stage evolution, Kauffman was searching for the initial conditions that allowed life to coalesce from a primordial soup, where “survival of the fittest” could not yet work its invisible hand.

The lessons of At Home in the Universe would also find application beyond the laboratory. In 1996, after his position of senior professor at sFi was terminated for what he calls “strategic vision reasons,” Kauffman founded BiosGroup, a consulting firm that applied complexity to problems as diverse as the streamlining of Procter & Gamble shipping routes and the potential effects of a stock’s initial public offerings. Kauffman notes proudly that BiosGroup was a leader in recognizing that “businesses are more like organisms co-evolving with one another and adapting to one another than Newtonian machines.”

The venture started promisingly, with start-up grants of $5 million each from Ernst & Young and the Ford Corp., along with an impressive list of clients that included the Nasdaq stock exchange and the U.s. Joint Chiefs of staff. However, as the economy collapsed in the dot-com crash of the late 1990s, the money for BiosGroup’s innovative research simply dried up. despite valuations of the company as high as $80 million, BiosGroup was eventually sold to NuTech Solution Inc., a North Carolina holding company on whose board of directors Kauffman sat until 2007.

The failure of BiosGroup seemed only to remind Kauffman that his primary love was for the laboratory, and the following year he accepted an offer from the University of Calgary to head its Institute for Biocomplexity and Informatics. Kauffman calls it “a watered-down version of the santa Fe institute.” it is quickly gaining prominence as a think tank and research institute that’s made promising research into the differentiation of cancer cells and powerful gene sequencing capabilities. Kauffman also holds an informal “crazy salon,” where scientists are encouraged to toss around the kinds of improbable ideas that fueled SFI.

There were also personal reasons for the move to Canada. speaking with barely restrained disdain, Kauffman laments “the constant drumbeat of fear” that, under George w. Bush, both disgraced the United States on the world stage and discouraged scientific research, such as the use of stem cells.

Holding back is not one of Kauffman’s virtues. in promoting Reinventing the Sacred, for example, he tackled the big question “does science make belief in God obsolete?” in an essay for the templeton Foundation. Kauffman’s answer is decidedly complex. “No,” he writes, “but only if we continue to develop new notions of God, such as a fully natural God that is the creativity in the cosmos….God is too narrow a stage for our full human spirituality... we can now choose to assume responsibility for ourselves and our world.”

Such an assertive formulation of divinity is certain to stir skepticism. Mark McPeek, a biologist at Dartmouth who is familiar with Kauffman’s work, says, “scientists can’t know what God is thinking about. we haven’t proved or disproved the existence of God. science stops at that point.”

Princeton’s dr. levin, however, calls Kauffman “one of the most inspirational people in the field” for his ability to explore new ideas with boundless passion, and notes that criticism of Kauffman’s work is largely the byproduct of his ambitious agenda. Whether his theological ideas will find traction in an intellectual marketplace already crowded with competing notions of God remains to be seen. But at the very least it is safe to say that the final act of Kauffman’s play remains unwritten.

High Climber The genius grant winner says his greatest honor was leading the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club.

HE'S BEEN CALLED "ONE OF THE MOST INSPIRATIONAL PEOPLE IN THE FIELD" FOR HIS ABILITY TO EXPLORE NEW IDEAS WITH BOUNDLESS PASSION.

ALEX NAZARYAN is a freelance writer and public high school teacher. He lives in New York City.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA World of Difference

May | June 2009 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04 -

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJames Wright

May | June 2009 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

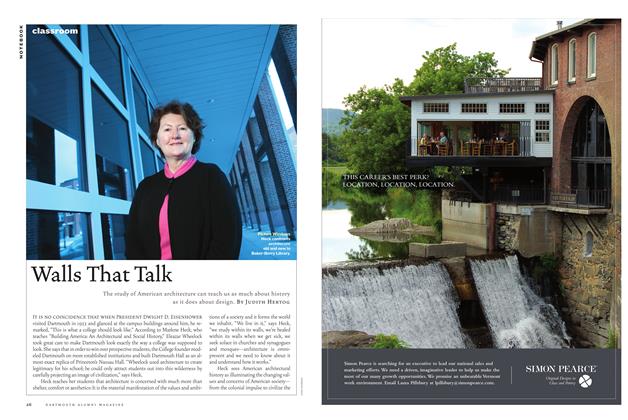

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May | June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSlow Medicine

May | June 2009 By Dennis McCullough, M.D. -

SPORTS

SPORTSIn a League of His Own

May | June 2009 By Brad Parks ’96

ALEX NAZARYAN ’02

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHE DUG DEEP TOO

October 1956 -

Feature

FeatureBoston Bookmaker

May 1974 -

Feature

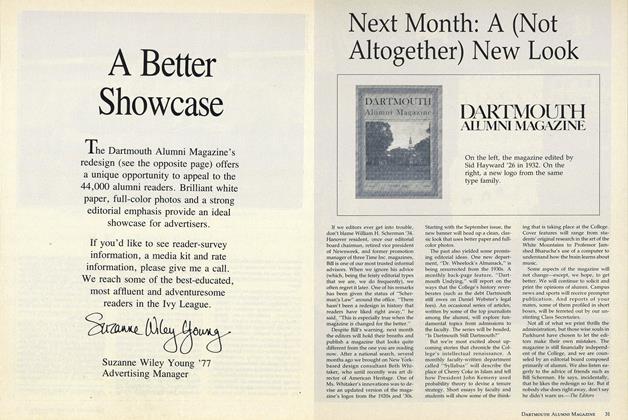

FeatureNext Month: A (Not Altogether) New Look

June • 1988 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryROSTER OF DARTMOUTH'S GIFTS TO THE WORLD

APRIL 1994 -

Feature

FeatureAll the Presidents's People

SEPTEMBER 1981 By J. N. -

Cover Story

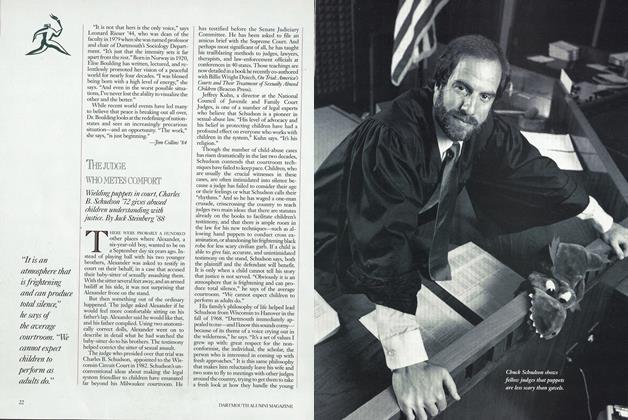

Cover StoryTHE JUDGE WHO METES COMFORT

JUNE 1990 By Jack Steinberg ’88