"IF IT be romance, if it be contrast, if it be heroism we require, what was Troy to this?" wondered Robert Louis Stevenson about the continent-spanning railroad and the brave, bold men who conceived it. His was a vision in sharp contrast to the stereotype currently in vogue of small-minded, powermad technologists bent on despoiling Mother Earth.

The images are equally inaccurate and unfair, says SAMUEL C. FLORMAN '46, by vocation a civil engineer, by avocation a writer, lecturer, and unofficial spokesman for the profession. The engineers who concoct the paraphernalia of modern society no more deserve the coals heaped upon their heads than did their predecessors merit the adulation of a generation that made larger-than-life benefactors of mankind of their builders. "Worship or blame, it comes to the same thing - a view of engineering as a messianic calling."

The "spokesman" mantle fell on Florman's shoulders first and foremost by reason of his obvious aptitude for articulating the problems and potential of his profession. He himself suggests that "It's because I've always had this double urge to be a mathematician, an engineer, and yet something else quite different."

Florman's own two worlds of culture and technology have roots deep in his childhood, in his family and his schooling. His love of learning is in part, he says, "the natural outgrowth of the engineering experience at Dartmouth,' where the liberal arts are part of the founding philosophy of the Thayer School." It stems too, ironically, from the exclusive company of his fellow Seabees, as they island-hopped across the Pacific during World War II. "I got the feeling that we were not as broad-based or as well- educated as we should have been. I remember," he says, wincing, "the chaplain telling us we were an awfully dull group."

Out of the Navy, armed with the G.I. Bill, and acutely aware of the gaps left by overspecialization as an undergraduate on an accelerated schedule - "I ignored what Dartmouth was trying to offer me" - he spent a year earning a master's degree in English literature at Columbia. "I was like a kid in a candy shop," he recalls.

After that year "I felt I owed myself," sitting at the feet of such giants as Lionel Trilling, Joseph Wood Krutch, and Jacques Barzun, Florman settled into professional life. He worked briefly in Venezuela, then for several different companies in New York, meanwhile taking evening graduate courses in engineering at NYU. Then in 1956 he joined Kreisler-Borg, a young Westchester County construction firm. A year later, he bought into the company, of which he has since been vice president and treasurer.

Kreisler-Borg has come to specialize in large subsidized housing projects; their contracts have run as high as $23 million, but fall generally in the $5-to-10-million range. They have built all sorts of structures, and they offer design and management services, but the firm's reputation is most thoroughly established in public housing. Although Florman remembers as the most interesting job, from a technical standpoint, an underground radiology laboratory for Mt. Sinai Hospital, and as the most aesthetically satisfying, Temple Israel in New Rochelle, he is reconciled to the reality that, as Kreisler-Borg grows more experienced, more adept, and more widely known for housing projects, they will inevitably come to specialize more and more narrowly.

In his writing - two books and countless articles - and in his frequent speaking engagements on campuses and before professional societies, Florman preaches the gospel of liberal learning, for the benefits that accrue to one's personal life and to one's professional career as well. "There is a world of wisdom and beauty to be won," he proclaims in Engineering and the LiberalArts, going on to recommend lists of listening and reading - in history, philosophy, literature, art, and music - that, faithfully followed, should qualify the student for a degree in the humanities, in absentia if not honoris causa.

Florman does not neglect the practical benefits of liberal learning. He deplores the over-emphasis placed on the dollars-and-cents value by some engineering educators - "it's all very good and very true, but it leaves a bitter taste in the end" - but he does not deny the contributions a broad educational background can make toward professional competence and advancement. With the day long gone when the solitary inventor wrought miracles in his laboratory or the wind-burned loner surveyed the high country for a new railroad cut, engineering has become a group enterprise, he points out, and "If you can express yourself better and understand how to deal with ideas and with words, you will achieve your ends more effectively." Harder to define, but of even more importance: "To have a livelier imagination, to exercise your brain with ideas and a variety of ideas, just has to contribute to your total ability to create and to understand."

But the most significant benefits remain, he insists, in the quality of one's private life, and the significance increases as the workaday world grows more specialized and organizations larger and more impersonal. "The narrower your professional life gets to be, the more you need a broad, free life on your own." His advice to young engineers: "It is important to have a private life with your own ideas, your own interests, your own hobbies, your own pleasures, your own philosophy. Develop the private resources to feel your own life is worthwhile in a private way...."

Sam Florman practices what he preaches. A reverse commuter, he feasts freely on the lavish cultural menu New York City offers. His wife, a teacher, is as devoted to ballet as he is to opera, and they share each other's pleasures at neighboring Lincoln Center. He makes music for fun, but claims only spectatorship on a serious level. As to how all the facets of his crowded life are accommodated within the 24-hour day accorded us all, Florman says, "I have learned to steal a little time here and there - from vacation, from weekends, from a working day." At least every three weeks, he takes a full day off to write.

As a contributing editor of Harper's, he ranges over an array of topics, some only peripherally connected with engineering. In "Wrong Way on the 8:10," he dwells on the delights of un- crowded trains and city evenings; in "Small Is Dubious," he counters the philosophy that big is bad per se and that self-sufficiency is invariably efficient; in "Technology's Minor Moments," he reviews some spectacular failures of the trade, such as General Motors' ill-timed investment in the Wankel engine. He warns of a scientific establishment that could politicize technology and stifle dissent. In "Another Utopia Gone," he casts a skeptical eye on "the gentle sophistries of the Club of Rome" - "a romantic neo-idealism" calling for no less than a change in human nature.

He defends his confreres from the burden of moral respon- sibility for public safety, health, and welfare that zealots of Left and Right would have them bear. "Technology is the expression of the total will of society," he responds, reminding critics that engineers have no vested interest in large cars over small, or cars in general over mono-rails. "Society gets the technology it wants."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

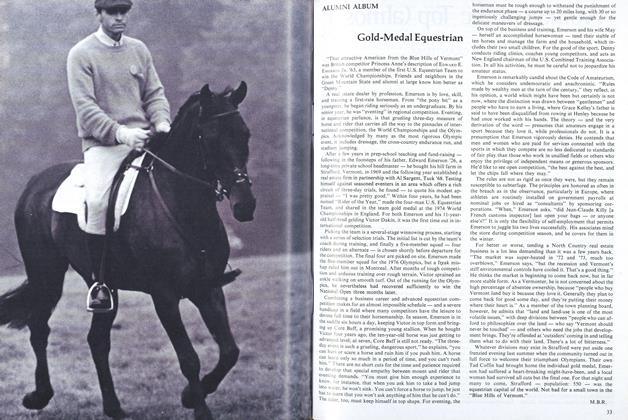

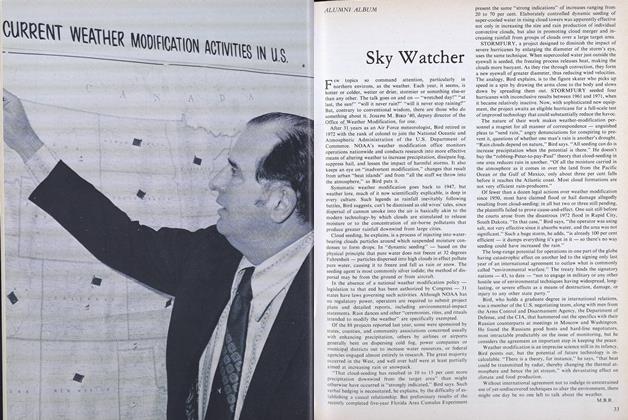

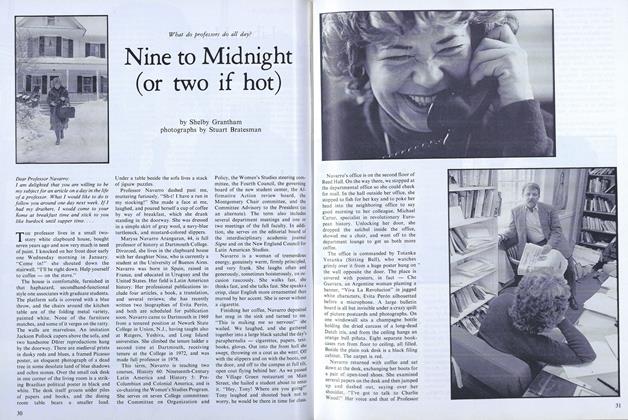

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

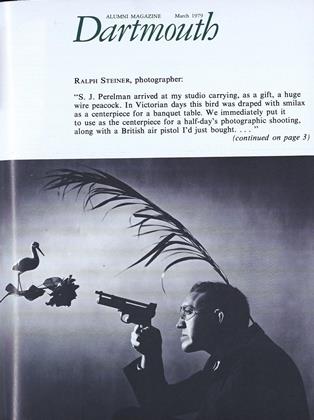

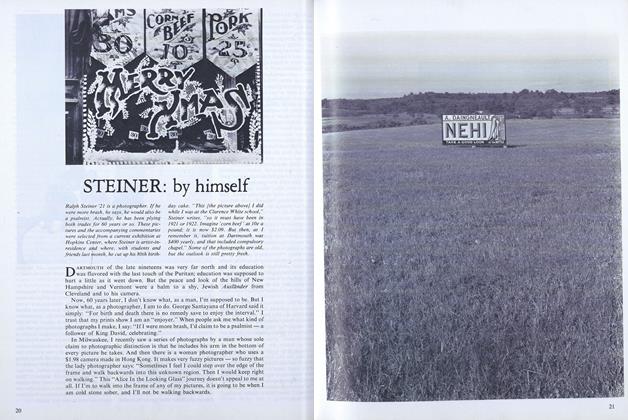

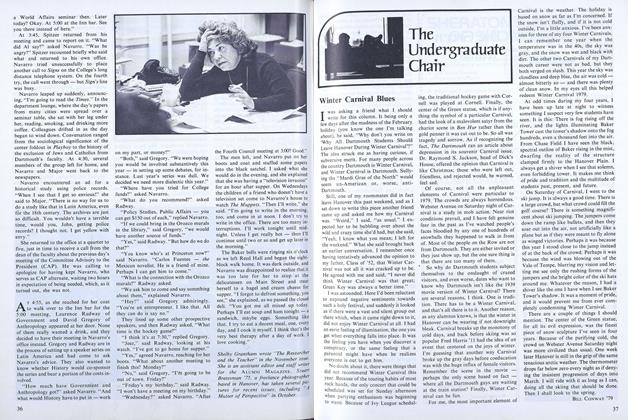

FeatureSTEINER: by himself

March 1979 -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Article

ArticleWinter Carnival Blues

March 1979 By Biĺ Conway '79 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1979 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1979 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.

M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMANAGERSHIP NOMINATIONS

February, 1909 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY AT MEETINGS OF LEARNED SOCIETIES

January 1916 -

Article

ArticleA Fantasy Life

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Abigail Drachman-Jones ’03 -

Article

ArticleJOINING THE INDIAN CAMP

JUNE 1968 By ALBERT C. JONES '66 -

Article

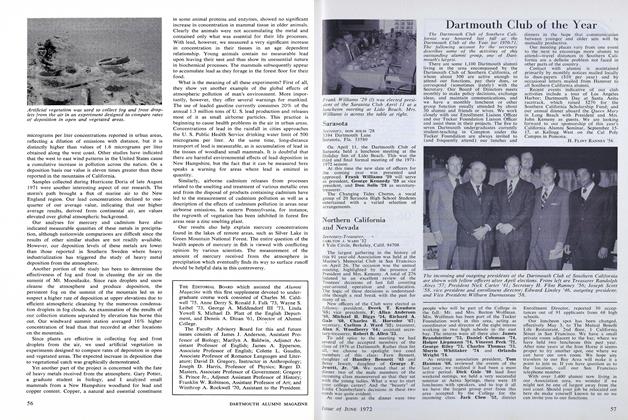

ArticleDartmouth Club of the Year

JUNE 1972 By H. FLINT RANNEY '56 -

Article

ArticleForgotten Dartmouth Men

May 1936 By J. ALMUS RUSSELL '20