LAST SPRING I WAS ASKED TO speak to an alumni audience on the topic, "The New Great Issues." The title, of course, alludes to the curricular initiative that President John Sloan Dickey started in 1947 and that continued until 1966. The program, which brought speakers of international repute to the campus and organized academic programs around their talks, was an impressive influence on the lives of a generation of Dartmouth undergraduates.

A Harvard Law School graduate and State Department diplomat. President Dickey came to Dartmouth in 1945 concerned with the great issues of international order, world peace, and human rights. He was eager to engage the undergraduates in the crucial issues of the day.

"Today our seniors," President Dickey said, "leave college without a fully developed sense of common public purpose, as Dr. Tucker used to call it, 'public mindedness.' They lack that sense of intellectual unity which in part at least is aroused simply through the common study of live issues."

"Great issues," Mr. Dickey asserted, "are not irrelevant to liberal learning; rather, they are the ladder on which human beings climb to their liberation." Clearly President Dickey had the most idealistic of hopes for what a liberal education would do for Dartmouth undergraduates.

The first visiting lecturer of the Great Issues course was Archibald MacLeish, poet and playwright, four-times winner of the Pulitzer Prize, lawyer, Assistant Secretary of State, Librarian of Congress, advisor and speech writer to President Roosevelt.

MacLeish asserted "that there is in truth and in fact an application to life of the liberal arts curriculum... that the purpose of a liberal education is neither to furnish a room in an ivory tower nor to qualify a man for membership in a bankers' country club, but to prepare him to live his 1ife....1t must be possible," he continued, "to apply the results and consequences of a liberal education to the various situations which life, from time to time, presents...to bring to bear upon these situations...the knowledge relevant to them and the discipline of minds by which that knowledge can be made useful and effective."

President Dickey went out of his way to bring to the College speakers of unusual capacity. They included Alexander Meiklejohn, Lewis Mumford, Edward U. Condon, Robert K. Carr, Reinhold Niebuhr, Beardsley Ruml, George F. Kennan, Erich Fromm, Henry Steele Commager, Barbara Ward, Ben Shahn, McGeorge Bundy, Hans Morgenthau, David E. Lilienthal, and Susanne K. Langer.

In looking at the history of the Great Issues course, and in examining the texts of the 60 Great Issue lectures preserved in Baker Library, I was especially struck with two facts. First, 58 of the 60 lectures were given by men. Only two were given by women—Barbara Ward and Susanne K. Langer. A Great Issues course today, I expect, would have a very different balance between men and women.

I was also struck by how much of the Great Issues course—especially in its early years—focused upon what was indeed one of the great issues of that day—the issue of communism: communism in the United States, communism in universities, communism in the State Department, and, of course, the threat of communism from the Soviet Union. But there were very few lectures having anything to do with Asia, the Middle East, Africa, or South America, as there surely would be in such a course today.

Of course, a Great Issues course today would address itself to the fundamental concerns of President Dickey and Archibald MacLeish— issues of war and peace, life and death, good and evil. Such a course today would still touch upon issues related to the legacy of the cold war, the rebuilding of eastern Europe, the effectiveness of the United Nations, and global shifts of power. But it would also consider new issues—ethical issues, for example, that arise out of medical care and research, issues about the environment, science, and technology. It would also consider issues of nationalism and factionalism—in countries like the former Yugoslavia, the former Soviet Union, and the Middle East. These issues go to the very notion of democracy and the consent of the governed, to our capacity to compromise, to our willingness to be tolerant. And it would surely consider issues concerning race relations, including issues of national cohesion—unity and separatism amongst ethnic groups—both in the United States and abroad.

As I read the history of the Great Issues course at Dartmouth, I especially admired how prescient President Dickey was in bringing those issues to the attention of our students, and how important it was to do that immediately after World War II, when we inherited a curriculum based on judgments made in a very different time.

My great hope is that as Dartmouth implements its new curriculum, we not lose sight of the importance of the kinds of great issues— the overarching questions—that President Dickey placed before our undergraduates. It is those great issues—an understanding of them and a capacity to think about them clearly, skeptically, rationally, and humanely—that finally are the mark of a liberal education. Dartmouth's great success in years past—and its only justification in the years ahead—is the quality of the liberal education that we give to the young men and women who study here,

"It is those great issuesthat finally are themark of a liberaleducation."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

October 1994 By Varujan Boghosian -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhere did the Mob go Wrong?

October 1994 By Tom Avril '89 -

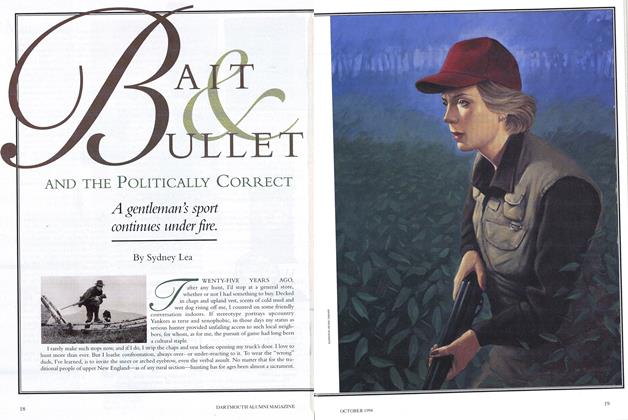

Feature

FeatureBait & Bullet and the Politically Correct

October 1994 By Sydney Lea -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Testa Hit

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Stanfa Hit

October 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Merlino Miss

October 1994 By George Anastasia

James O. Freedman

-

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleTHE CONCEPT OF HEROISM

MAY 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Lifelong Pursuit of Education

Winter 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTowering Silences

APRIL 1997 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Uncertain Future of Medical Education

DECEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleSMOKE TALK BY NORMAN HAPGOOD

February, 1909 -

Article

ArticleRADIO CLUB TO ESTABLISH PORTABLE STATIONS AT OUTING CLUB CABINS

March 1921 -

Article

ArticleMedical School Contributors

December 1955 -

Article

ArticleFifty-Year Address

July 1953 By EDWARD HIBBARD KENERSON '03 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

May 1962 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M'27 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

MARCH 1968 By ROBERT Y. KIMBALL T'48