IT must be a breeze, you figure, to manage the endowment of a college like Dartmouth. All you have to do is buy some good, sound stocks, plus some safe bonds (isn't their yield amazing these days!), plus maybe some mortgages. Then make a list of a few more prospective good buys, against the time when new money comes in or some of the old stuff matures, and you've got it made. Sounds like a lazy man's job, right?

You couldn't have it wronger. Of all the hair-raising, nail-biting occupations around, managing Dartmouth's endowment is certainly one of the hairiest. For example, it is partly because of what that endowment did or, more correctly, failed to do, by failing to keep pace with inflation as expected that we have a Campaign for Dartmouth in full cry today, with all the hundreds of thousands of hours of voluntary and paid labor involved. That endowment must be managed by people with an intimate knowledge of post-war financial history, combined with the sure realization that history will not repeat itself. Managing the endowment is an inescapable responsibility: The failure to act can have as grave consequences as taking wrong moves. And not only will any mistakes inevitably be pointed out by critics with 20/20 hindsight; they will also drain the College's vital sustenance.

The endowment is managed by the trustees' investment committee, whose regular members are William H. Morton '32 as chairman, Richard D. Lombard '53 as vice chairman, Richard Hill '4l, Walter Burke '44, and Norman E. McCulloch '50; sitting as a member with them is Dartmouth's vice president for investments, Paul D. Paganucci '53. The committee does not lack for expertise: For example, Morton retired recently as president of financial giant American Express; Lombard ran his own Wall Street investment counseling firm; and the other members (such as Hill, who is chairman of the First National Bank of Boston) are equally sophisticated financially. Paganucci, the committee's full-time working member, was once a Wall Street partner of Lombard before joining Tuck School in 1972, from which he moved to replace the late John F. Meek '33 in mid-1977 as the College's number one financial wheel.

The endowment they manage just over $200 million as of December 31 is far from the largest among American universities, and certainly not in a class with Harvard's $1.5 billion or Stanford's, Yale's, Princeton's, and Columbia's half-billion-plus each. It ranks between 15th and 20th among all domestic universities, and is third from the bottom of the eight Ivy League schools; only Brown and Pennsylvania are clearly lower.

Not all that $200 million in market value of assets is "manageable" in a financial sense, however. Some $40 million-plus is in assets that the College cannot freely sell, or thinks it would be impolitic to sell, or hesitates to sell for various special reasons. One category here would be mortgages on Hanover and other real estate. Another would be securities whose sale is subject to certain Securities & Exchange Commis sion restrictions for example, about $1 million worth of McDonald's Inc. stock recently given the College. Still another is stock in companies whose sale might discourage the donors from making further gifts. All told, notes investment committee chairman Morton, "Our investment that is subject to mobility is really about $140 million or $145 million."

It is in the management of this mobile money that Dartmouth in the last few years suffered a threateningly serious slip, followed by what appears to be as least so far a most satisfactory recovery.

THE first decision about the endowment is so basic that not even the investment committee presumes to decide for itself, but makes a recommendation to the full Board of Trustees: What shall be the ratio between equity securities (generally common stocks), which customarily provide lower current income but have a chance for capital appreciation, and fixed-income securities (generally bonds), whose current yield tends to be higher? The only limit that the full board has imposed as to ratio is that neither equities nor fixed-income securities may be less than 25 per cent or more than 75 per cent of the endowment portfolio.

With an old bond-man chairing the investment committee, you might assume that the portfolio balance has been swinging to fixed-incomes. Not so. Listen to old bond-man Morton on the subject: "For one of the few times in my 45 years of experience in investments, for the last several months I have felt that well-selected companies with good products, hopefully with some access to natural resources, and good book values on replacement cost, represent a unique opportunity to buy equities." Partly because of that view, supported by the other committee members, the endowment's mobile assets have remained nearly two-thirds in equities and just over one-third in fixed-incomes.

To sustain that view over the last decade has taken courage that sometimes seemed to border on foolhardiness. Since the early 19705, the price performance of equities in general, as measured by the blue-chip Dow-Jones industrial index or the broader based Standard & Poor 500-stock index, has been wretched: Both indices are well below their levels in 1973, even without allowing for the further loss in real value because of the intervening years of inflation. For some fiscal years the "total return" on the equity portfolio figured by combining dividend return with change in price was actually negative, which at times led President John Kemeny to suggest, more than half-seriously, that the College consider putting all its mobile endowment in fixed-income securities. (Since August of 1977, in fact, virtually all new gifts received in the Campaign for Dartmouth which could be sold have been reinvested in fixed-income securities.)

But the fact remains that for over a decade, common stocks, when measured in another way, have kept pace with inflation. Stock prices, to be sure, have lagged; but since 1967 the earnings of the companies that comprise the Standard & Poor 500stock index have risen by 150 per cent versus a 117 per cent increase in the Consumer Price Index. Dividends have not quite kept up with the CPI, rising only 81 per cent; but for the last four to five years dividends, too, have been outstripping the CPI. The only question remaining - and a huge question it is - is whether one believes that in the not distant future the price of common stocks will rise to reflect the continuing earnings and dividend gains.

It was the poor price performance of the equity part of the portfolio that threatened the endowment with serious trouble and led to the well-organized recovery. The general shepherding of the College's financial affairs was for some 30 years in the capable hands of John Meek, who was successively treasurer of the College, vice president, and chairman of the investment committee. Near the end of 1951, the trustees hired Colonial Management Co. of Boston as outside investment manager for the entire portfolio, equities and fixed-income securities alike, and worked closely with it for the next quarter of a century. Colonial not only carried out buy and sell orders; it was also expected to recommend portfolio changes and was given, within limits, considerable discretion in making purchases and sales. For some two decades the arrangement worked very well for both parties.

The troubles came, like so many financial troubles, as the 1970s wore on. In the eyes of Dartmouth's investment committee, the troubles stemmed from a major change in strategy. First, Colonial was traditionally considered to be a so-called "value" manager, meaning it sought out common stocks that for some quirk of financial fashion were undervalued by the market and could therefore reasonably be expected to rise as investors realized their mistake. But in the early 19705, Colonial made a conceptual switch toward becoming "growth-oriented" that is, toward stock of companies that might be selling at apparently outrageous levels now but whose future growth was considered certain to justify their current prices of 25 or 35 or more times earnings. (The blue-chip stocks in the Dow-Jones industrial index now sell for some eight times earnings.) Thus, the College's equity portfolio - with the concurrence of the investment committee, to be sure - began to lean toward the so-called "one-decision" growth stocks like Polaroid or Tampax or Avon Products, a collection then also known as the "Nifty Fifty." These stocks promptly proceeded, in the 1974-77 period, to fall much more disastrously than the rest of the stock market.

This was more than just a question of bad timing on Colonial's part. If there is any ultimate wisdom in the field of securities management, it is that a manager can be a long-term success by following any one of several strategies: Specifically, he can be a value manager, as Colonial was; or a growth manager, as Colonial aspired to become; or he can be a so-called "yield" manager, choosing stocks on the basis of their present and prospective level of dividends. Any of these strategies will work if pursued persistently and intelligently over a period of years. What will not work is to try to follow more than one strategy, or to get caught switching from one to another.

THE combined effect of these changes, in the market situation then prevailing, began to show up in some rather alarming figures. It was not merely that the College's equity pool showed a dip in unit value - that is, discounting the effect of new additions - of over 40 per cent between mid-1973 and the fall of 1974. "Jesus Christ couldn't have been right at that time," remarks Morton. (That sickening lurch was followed by a recovery over the next two years that brought the figure back by mid-1976 to over 90 per cent of mid-1973 levels.) What was more disturbing was that Dartmouth's equity performance began to show up more and more poorly compared with the stock market averages and certain other benchmarks (other capital pools) that the investment committee followed regularly.

What finally iced the cake was a sudden dip, toward the end of 1976, of about oneeighth in the unit value of the equity portfolio. At that point the investment committee moved in and, early in 1977, withdrew Colonial's discretionary powers to make transactions for the College unless approved in advance by three trustees. By then, too, the committee had made up its mind to change its investment procedures ("we may have made it two years too late," worries Morton) to a so-called multiple management approach of which more below. At that time the committee did not rule out the possibility of some more limited continuing relationship with Colonial. But it did not happen, and in the early fall of 1977 F. William Andres '29, then just retired chairman of the trustees, walked a letter over from his office in Boston to Colonial's office, terminating its quarter-century-old relationship with Dartmouth.

Richard Lombard, who succeeded John Meek as chairman of the investment committee, credits Meek with softening the imct of the growth-stock collapse of the early to mid-1970s by pressuring Colonial to stay more heavily in cash rather than follow the standard practice of keeping fully invested. Meck's last great financial service to the College, before his sudden death in early 1978, was to act as secretary and working executive of the committee to choose Colonial's successors. During his tenure he had nursed the Dartmouth endowment through a six-fold increase, from just over $26 million to nearly $160 million at his departure on June 30, 1977.

That search was deeply influenced by the events just passed: If growth stocks could suddenly fall out of bed, then so could stocks picked by any other single criterion. For an institution that had to depend on its investment income, and therefore was vulnerable to wide swings in endowment value, the more sensible course seemed to be diversification - that is, picking several outside investment managers with clearly contrasting strategies, in the hope that a temporary disappointment in one strategy might be offset by success in others.

With this objective clearly in mind, some 45 competing investment firms were interviewed in the spring and summer of 1977, and many called back for exhaustive second sessions. Then, after lengthy discussions on fees, three equities managers were chosen: Pioneering Management Corp. of Boston as a value-oriented manager; Delaware Investment Advisers of Philadelphia as a yield-oriented manager; and T. Rowe Price of Baltimore as a growth-oriented manager. The three equity managers were each assigned some $25 million to manage according to their sharply divergent strategies. While the three managers were appointed at slightly differing dates, all were in place and ready to operate by the beginning of October 1977. Soon after, a manager had also been chosen for the fixed income portfolio, State Street Research & Management Co. of Boston.

How have they been doing? So far, remarkably well. In the two and a quarter years ended December 31, 1979, the smallest total-return gain - that is, dividends plus increase in market value- among the three equity managers was 36.4 per cent, by the yield manager. The highest, by the growth manager, was 45 per cent. This compares with an increase of 13.1 per cent for the Dow-Jones industrial index (calculated on the same basis) and 26.3 per cent for the Standard & Poor 500. Over the same period the College's bond portfolio, in a very bad bond market, was showing a total-return gain of 4.9 per cent when the standard Salomon Bros, or Lehman-Kuhn, Loeb indices were showing declines of several percentage points.

One result of all this is that Dartmouth's entire equities-plus-bonds portfolio enjoyed a total return of nearly 30.4 per cent over the period, mainly because of a 44 per cent return from the equities side. A more important result is that the endowment's market value reached an all-time high of $202.7 million on December 31, 1979.

So now, you figure, the investment committee has the situation pretty well under control. Are you kidding? Don't you realize that the October blood bath in bonds drove down the Salomon Bros, bond index nearly 10 per cent on a principal basis, helping to shrink the College's total endowment by $10 million in a single month? Doesn't it worry you that three equities managers with sharply different strategies have been performing about the same? It worries the investment committee. What do you do when you find two of your equities managers buying the same stock? Are they keeping their explicit agreement to follow their separate strategies? What do you do if - it has already happened - a top executive working on your account decides to leave one of the managers? Does your whole reasoned approach make sense in a world swayed more and more by zealots like the Ayatollah Khomeini?

No hiding place down here.

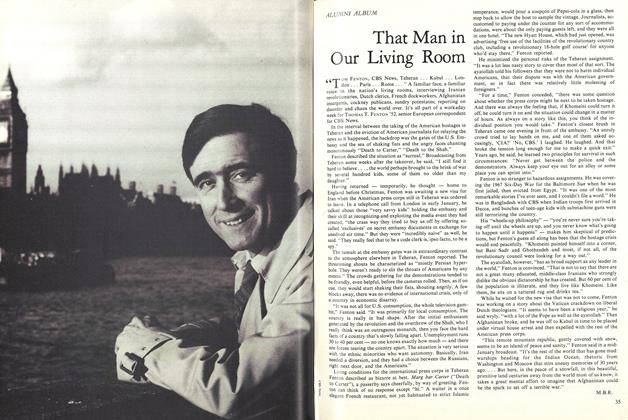

Cigars all around: investment and legal officers (seated, from right) Paul Paganucci '53 and Cary Clark '62 and (standing, from right) Bruce Dresner, Tuck '71,Tom Csatari '74, 'and Norman Richter '79. They lit up from Paganucci's privatestock shortly after Dartmouth's endowment reached its high of $202.7 million.

Dero Saunders '35 is executive editor of Forbes magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

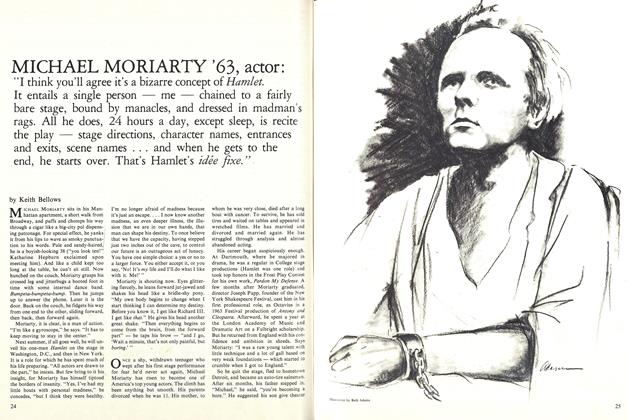

Cover Story

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleThat Man in Our Living Room

March 1980 By M.B.R.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Transcending Great Issues

OCTOBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council to Meet

JANUARY 1971 -

Feature

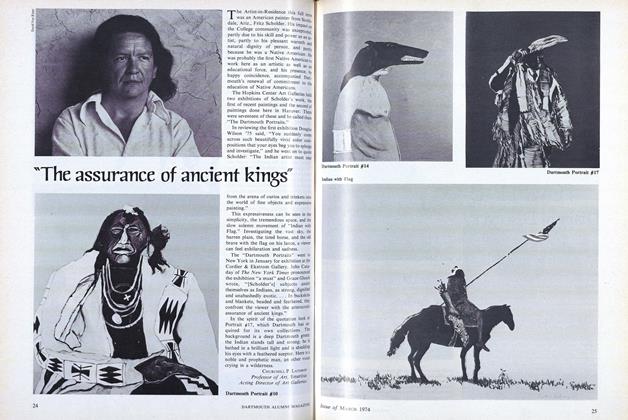

Feature"The assurance of ancient kings"

March 1974 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Feature

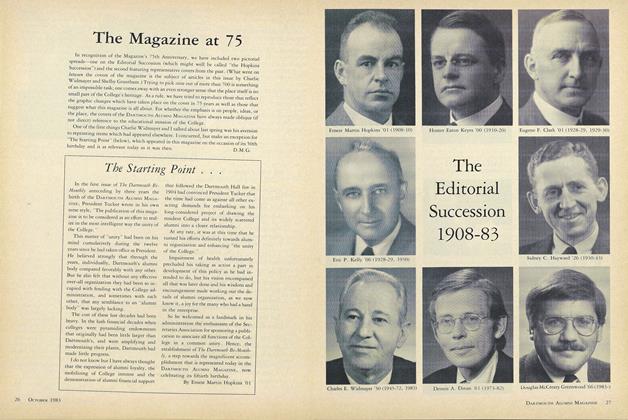

FeatureThe Magazine at 75

OCTOBER, 1908 By D.M.G. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLooking for Mr. Goodjob

MAY • 1987 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Feature

FeatureWDCR Reports

MARCH 1968 By LAURENCE G. BARNET '68