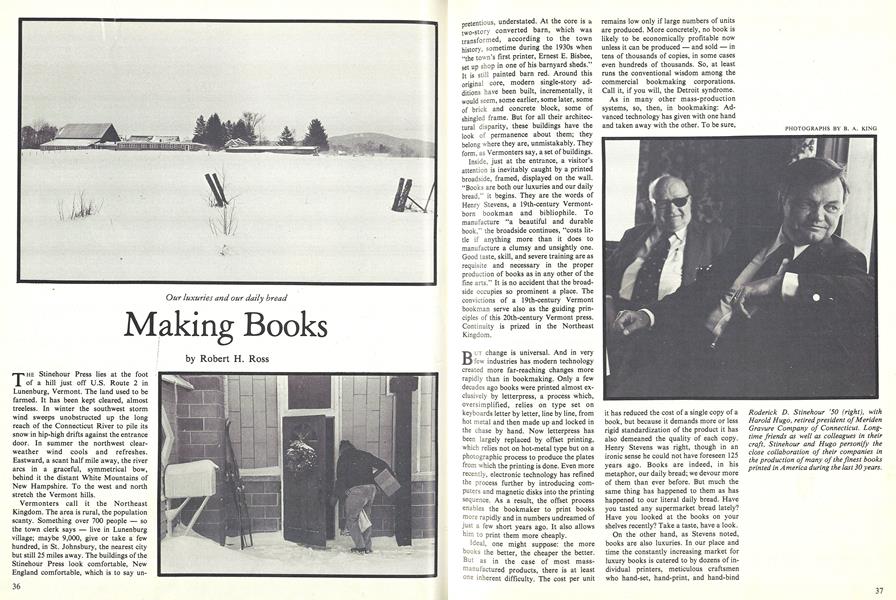

The Stinehour Press lies at the foot of a hill just off U.S. Route 2 in Lunenburg, Vermont. The land used to be farmed. It has been kept cleared, almost treeless. In winter the southwest storm wind sweeps unobstructed up the long reach of the Connecticut River to pile its snow in hip-high drifts against the entrance door. In summer the northwest clearweather wind cools and refreshes. Eastward, a scant half mile away, the river arcs in a graceful, symmetrical bow, behind it the distant White Mountains of New Hampshire. To the west and north stretch the Vermont hills.

Vermonters call it the Northeast Kingdom. The area is rural, the population scanty. Something over 700 people-so the town clerk says-live in Lunenburg village; maybe 9,000, give or take a few hundred, in St. Johnsbury, the nearest city but still 25 miles away. The buildings of the Stinehour Press look comfortable, New England comfortable, which is to say unpretentious, understated. At the core is a two-story converted barn, which was transformed, according to the town history, sometime during the 1930s when "the town's first printer, Ernest E. Bisbee, set up shop in one of his barnyard sheds." It is still painted barn red. Around this original core, modern single-story additions have been built, incrementally, it would seem, some earlier, some later, some of brick and concrete block, some of shingled frame. But for all their architectural disparity, these buildings have the look of permanence about them; they belong where they are, unmistakably. They form, as Vermonters say, a set of buildings.

Inside, just at the entrance, a visitor's attention is inevitably caught by a printed broadside, framed, displayed on the wall. "Books are both our luxuries and our daily bread," it begins. They are the words of Henry Stevens, a 19th-century Vermontborn bookman and bibliophile. To manufacture "a beautiful and durable book," the broadside continues, "costs little if anything more than it does to manufacture a clumsy and unsightly one. Good taste, skill, and severe training are as requisite and necessary in the proper production of books as in any other of the fine arts." It is no accident that the broadside occupies so prominent a place. The convictions of a 19th-century Vermont bookman serve also as the guiding principles of this 20th-century Vermont press. Continuity is prized in the Northeast Kingdom.

But change is universal. And in very few industries has modern technology created more far-reaching changes more rapidly than in bookmaking. Only a few decades ago books were printed almost exclusively by letterpress, a process which, oversimplified, relies on type set on keyboards letter by letter, line by line, from hot metal and then made up and locked in the chase by hand. Now letterpress has been largely replaced by offset printing, which relies not on hot-metal type but on a photographic process to produce the plates from which the printing is done. Even more recently, electronic technology has refined the process further by introducing computers and magnetic disks into the printing sequence. As a result, the offset process enables the bookmaker to print books more rapidly and in numbers undreamed of just a few short years ago. It also allows him to print them more cheaply.

Ideal, one might suppose: the more books the better, the cheaper the better. But as in the case of most massmanufactured products, there is at least one inherent difficulty. The cost per unit remains low only if large numbers of units are produced. More concretely, no book is likely to be economically profitable now unless it can be produced-and sold-in tens of thousands of copies, in some cases even hundreds of thousands. So, at least runs the conventional wisdom among the commercial bookmaking corporations. Call it, if you will, the Detroit syndrome.

As in many other mass-production systems, so, then, in bookmaking: Advanced technology has given with one hand and taken away with the other. To be sure, it has reduced the cost of a single copy of a book, but because it demands more or less rigid standardization of the product it has also demeaned the quality of each copy. Henry Stevens was right, though in an ironic sense he could not have foreseen 125 years ago. Books are indeed, in his metaphor, our daily bread; we devour more of them than ever before. But much the same thing has happened to them as has happened to our literal daily bread. Have you tasted any supermarket bread lately? Have you looked at the books on your shelves recently? Take a taste, have a look.

On the other hand, as Stevens noted, books are also luxuries. In our place and time the constantly increasing market for luxury books is catered to by dozens of individual printers, meticulous craftsmen who hand-set, hand-print, and hand-bind small numbers of titles in severely limited editions. After the sheets are printed they destroy their type forms; that particular edition can never be duplicated. Because of such deliberately created scarcity, their books demand high prices from collectors, who prize them not so much for their content as for the bookmaking craftsmanship which they exemplify. Even among the most selfless bibliophiles, however, dollars-and-cents considerations are seldom irrelevant. A private-press book in a limited edition is, after all, not only a thing of intrinsic beauty but also an investment. The economics is simple: Because supply has been made finite, value must increase-or so the collector hopes-as time and scarcity combine to increase demand. More often than not, if he has bought wisely, the collector is right.

And so, if the large commercial bookmaking corporation cannot show its stockholders a profit without mass production and the small cottage-industry bookmaker cannot succeed with it, which will we choose: Assembly-line books that are daily bread, nothing more? or handcrafted books that are caviar, nothing less? Fortunately, we are not at the point of such a stark either-or choice, not yet anyway. For dotted across the country are several points of light, a few presses-small by commercial standards-that stubbornly persist in defying the cult of bigness by daily validating the premise that finely printed books on serious subjects and in editions of modest numbers can not only be successfully manufactured but can also make their own way in the marketplace. David R. Godine '66, head of the Godine Press in Boston, recently summarized their credo: "We celebrate books as both transmitters of information and objects of intrinsic beauty-products which are more than pieces of identical, disposable merchandise to be cheaply produced and quickly remaindered. If a book is worth publishing, it is worth manufacturing well."

Though not, like the Godine Press, a book publishing house, Stinehour Press operates on a shared assumption: Do it well or not at all. Stinehour Press began 30 years ago when Roderick D. Stinehour '50, fresh from his Hanover commencement and several years of apprenticeship in the workshop of Professor Ray Nash, moved upriver to Lunenburg and bought the press that Ernest Bisbee had set up "in one of his barnyard sheds." Like that of many other undergraduates in the 19405, Stinehour's education had been war-interrupted. Having left college to serve in the Navy during World War 11, he delayed his return until he had also served as a printer's apprentice for a year in Ernest Bisbee's shop. And so "in a sense," Stinehour says, "Dartmouth was a kind of vocational school for me because by the time I returned I knew exactly the sorts of things I wanted to get from Dartmouth." What Stinehour wanted Ray Nash could give: a solid knowledge of printing, historical perspective, technical skill, respect for craftsmanship.

Other Dartmouth graduates have followed Stinehour upriver. Soon after his graduation John F. Melanson '54 joined the press and, with the exception of a short period in the 19605, has remained there ever since. Melanson is an expert technician; he operates the monotype machine, a complex piece of equipment that transforms the signals on a perforated paper tape into hot-meta'l type. But he is also a skilled craftsman; it was he who hand-engraved on boxwood the prototype of the Stinehour Press logo, the compass rose taken from a 1677 woodcut map of New England. More recently Stephen Harvard '70 joined Stinehour. Having developed his interest in lettering and graphics as an undergraduate under the tutelage of Ray Nash, Harvard has turned to book designing. But he, too, has several talents. He is a stonecutter and calligrapher who, using his wide historical knowledge of the evolution of the English alphabet, is now developing an alphabet for computers. Harvard designs, as Stinehour says, "special projects," particularly il- lustrated books.

That so sophisticated an enterprise as Stinehour Press, with its demand for such uncommon skills as Melanson's and Harvard's, should thrive in so unsophisticated a setting as the Northeast Kingdom seems in many respects, as Stinehour concedes, "something of an anomaly." The press is not large; it employs something around 40 people. Nevertheless, it succeeds in attracting and retaining "people with very specialized skills and capabilities that you wouldn't often associate with a small organization." Size aside, there is also the matter of location. The north country is not for everyone; the isolation is palpable. Taken all in all, however, Stinehour is convinced that far from being a detriment the location works as an advantage. "Because people can't just leave here and go to work for the printer next door," he points out, "we develop a great deal of interdependence and responsibility for one another. We all live together, go to the same churches, serve on the same town committees, and our social life is often the same. We don't just come together at the Press and then go our divergent ways. We live in a separate world up here, but we all live in it together." The people who choose the kind of life offered by the Northeast Kingdom "are kind of special," he concludes; "they like country living, they like working on significant things. Craftsmanship is the appeal that holds us together." Craftsmanship, that is, and the attraction of living in the north country.

Ulike some other observers of prese nt trends toward mass production in bookmaking, Stinehour is no handwringer. The future of the well-made book, he believes, is assured. He states his case succinctly: "There's no doubt in my mind that the kind of thing we're doing is useful, needed, and will continue." In fact, he adds, it is "exactly because the printing industry is getting an increasing ability to spew out junk, and because the market is being flooded with that sort of thing, that people are becoming more qualityconscious" rather than less.

The besetting problem for the small press is neither technology nor a lack of demand for its products. It is to maintain cost-effectiveness. Even well-made books must be affordable, and under the cost pressures induced by inflation, manufacturers of quality books run some risk of having to price their product out of the market. Even so, Stinehour believes, their niche is secure because the requirement for certain kinds of books in modest numbers remains constant. "The whole thing is a matter of scale," he says. "It really is." He elaborates: "When you're talking about a run of a few thousand books, those big commercial presses-huge mechanical monsters that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in capital investment-they can't even get warmed up. They're geared to do tens of thousands of books. A few thousand is an impossibility for them from the cost point of view." Yet the need for other kinds of printing persists; some books and journals must be produced in editions of only a few thousand. "Those things," as Stinehour says, "come here. We have to be careful to choose, to take on, only the kind of work that fits our niche."

By commercial standards, therefore, the output of Stinehour Press is small. It limits itself to producing no more than 50 to 60 books per year, and although an occasional edition may run as high as 5,000 copies, the average edition is only about 2,000. Nevertheless, its self-chosen niche is not so cramped as to preclude variety. In 1978, for instance, Joseph Hubert's Salmon,Salmon, printed for the Anglers and Shooters Press, required Stinehour Press to marshal its most specialized designing, printing, and manufacturing talents to meet such requirements as elaborate fullcolor reproductions, maps, a text printed in three colors, and a full leather binding. The edition was limited to 100 copies; its retail price was $1,000. During the same year, on the other hand, Stinehour continued to print the relatively straightforward quarterly issues of many scholarly journals in editions of 2,000 copies or fewer, and it printed a centennial history for the Cosmos Club of Washington, D.C., in an edition of 5,000 copies. Each exemplified, in its own degree, the same skill, attention to detail, and craftsmanship.

Such work has not gone unnoticed. The Stinehour Press, wrote Joseph Blumenthal in his authoritative history, The PrintedBook in America (1977), is "the only fine press in New England with a scholarly staff (headed by C. Freeman Keith) and a plant of sufficient size to be capable of turning out substantial, well-designed books and catalogues that maintain a high degree of craftsmanship." But being "in New England" does not imply that its reputation is confined to New England. Almost from the start, academic institutions Dartmouth among the earliest of them

museums, libraries, and art galleries across the country began turning to Stinehour Press to meet the special requirements of their kinds of publications. Indeed, its "superb catalogues for the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York," as Blumenthal notes, "have won international recognition." Blumenthal's highest praise is more implicit than explicit: He chose Stinehour Press to print his own book on the history of American bookmaking. That is no small accolade.

The process by which a manuscript becomes a printed book is long and complex. It begins when a publisher (or sometimes the author) submits a typescript to the press. A cost estimate is the first requirement, and so a book designer must develop a preliminary design concept taking into account such basic considerations as the purpose of the book, the optimum selling price, and the publisher's budget. Once established, the cost estimate is sent to the publisher. If it is accepted, the designer, working closely with the in-house copy editor, goes to work on the final design of the book. He must decide such matters as the typeface to be used, the printing process, the paper, the sheet size, and the binding. He will usually require sample pages to be printed, sometimes a binding dummy as well, in order to verify his design concept visually. After another check with the publisher, manufacturing can begin.

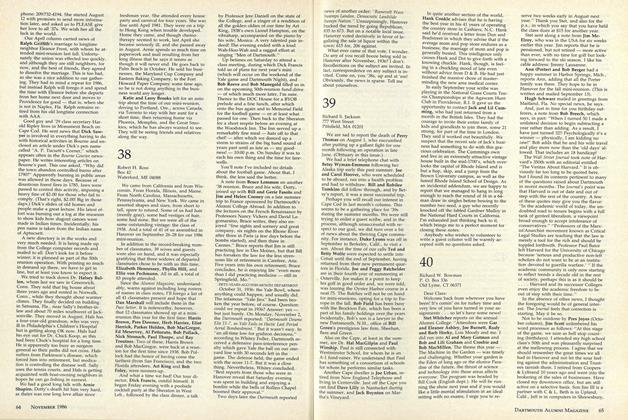

Typesetting comes first. The options at this stage depend on how the book will eventually be printed. If it is to be done by letterpress, as some still are, then in a few cases the type may actually be set by hand. More often the copy is transferred to perforated tapes, thence to be fed into a monotype machine that "reads" the tapes and casts type from hot metal. On the other hand, if the book is to be printed by offset, as most are, the copy is started through the Linoterm process, a computerized typesetting sequence which, by use of a film setter at the final stage, produces camera-ready copy for the offset press. While the typesetting is proceeding, halftones for the illustrations, if any, are also produced. Then come galley proofs-and the point at which the author gets the first chastening look at his words in actual print. Now both author and in-house copy editor work together on one of the most demanding chores of them all: proofreading. Between them they must pick up on the galleys-or so they hope-every error, however minute, and note every correction to be made. Corrected galleys in hand, the printer can then correct the type accordingly and run off a second set of proofs, this time page proofs. And then once more, proofreading. But since this is the second time around, the errors are, presumably, fewer (and the mistakes, at this advanced stage, inordinately expensive to correct). Finally, with verified page proofs in hand and the forms corrected for the last time, the printer gives the "O.K. to Print" order.

The average period at Stinehour Press between receipt of the author's typescript and the "O.K. to Print" order is something around three months. In some cases where additions to a complicated technical text were required during editing and typesetting, the pre-printing period has been known to extend to two years or more. Time, as Stinehour points out, is essential: "If you're going to do something well, you have to put time into it as well as skill. If you start to squeeze time and push. everything through, then you've removed one of the ingredients of the quality process. You've got to have time to check everything over twice and to do everything a bit more thoroughly than is ordinarily done."

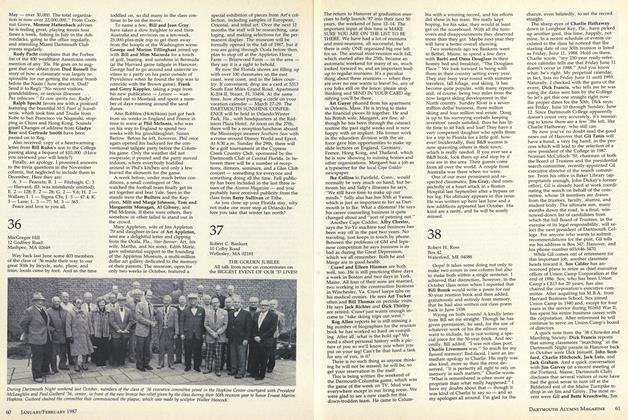

The actual printing, however, goes quickly. Though no doubt the most spectacular step in the bookmaking sequence -a modern printing press is a massive, even awesome, machine-the printing requires less time than any other. In the pressroom the forms are locked onto the bed of the press, the rollers inked, the switch thrown, and the whole improbable assemblage of wheels, gears, rollers, and rocker arms begins to whir. A modern press, of course, prints sheets, not pages, and each sheet has imprinted on it at least 8 pages, sometimes 16, even 32. Though not comparable to the huge commercial presses that can print book sheets for an edition of tens of thousands of copies in a day or two, the smaller presses used in quality printing nevertheless require no more than a week to complete sheets for an average 400-page book in an edition of 1,000 copies.

After all the sheets have gone through the press, they are sent to the bindery. In a small, quality press, binding, though mechanized, still involves a great deal of hand work; in large mass-production operations, however, it is, machines that fold the sheets into gatherings (if the printing press has not already done it), sew them together, trim them into pages, paste the spines, and bind them in whatever material the designer has selected. Finally, manufacturing has been completed; the book is identifiable as a book. It remains to distribute and to market it.

In its essentials book manufacturing is much the same everywhere. Stinehour Press follows most of the same steps in the same sequence as any other press. It, too, is mechanized. Indeed, as Stinehour notes, "all printing has to be mechanized, to a certain degree. It is a modular, repetitive business." But there is a significant difference, he quickly adds, between mechanization and an assembly line.

Though evident at every step of the process, nowhere perhaps is the difference more visible than in the emphasis which a quality press places on copy-editing and designing. Careful copy-editing produces accuracy; and "accuracy," as Stinehour says, "is the cornerstone of the operation." Not only does Stinehour Press maintain a large copy-editing staff, but its proofreading procedures are also unusually thorough. It often prints and sends to authors several additional sets of proofs beyond the number customarily submitted by larger printers. It is an expensive process, but as Stinehour concludes, "If accuracy isn't taken care of, then the rest of it is a bit superfluous. We don't want to whiten any sepulchers." Thumb-tacked to the wall above the desk of one of Stinehour's copy editors, a reminder printed in 72-point Baskerville type epitomizes the concern for accuracy. "Assume Nothing," it reads.

PERHAPS least understood of all the steps in bookmaking, designing is among the most important. A book does not just happen. Typeface, leading (the space between lines), margins, page size, illustrations, footnotes, running heads, paper, binding: They are technical matters, to be sure, but they are not mere technicalities. They are all interrelated, and they lie at the heart of bookmaking, for in the end they must all cohere in a harmonious whole if the book is to be not only a useful but an aesthetically pleasing object as well. It is the job of the designer to make them cohere.

Good design seldom results from the application of mass-production norms. To the quality press each book presents unique problems because each has unique aims. No one book is precisely like any other. A case in point is one of the recent publications of Stinehour Press: TheCollection of Germain Seligman: Paintings, Drawings, and Works of Art, edited by John Richardson (1979, 500 copies). Clearly, it was "a very special book from the start," says Stinehour. Its aim was to honor the memory of an internationally influential art historian, collector, and dealer; the method adopted by the editor was to describe, both visually and by printed text, the personal collection of the late Mr. Seligman in order "to show the nature of his interests, the breadth of his scholarship, and his acquisitional talents."

The first imperative, therefore, was flawless reproductions of paintings and other works of art. To that end graphics experts from Stinehour Press went to New York City to study available photographs of items in the Seligman collection. Only a few, they found, would reproduce well enough to meet the exacting standards of this particular book, and so they were required to re-photograph most of the works in the collection. In some cases they used no photographs at all. "We even brought original works of art back to the shop," Stinehour explains, "and put them in front of our own graphic arts cameras to screen directly and thus bring out certain subtleties of shadows and middle tones."

With high quality reproductions assured, the designer turned to the question of format. "Here,," as Stinehour points out, "form follows function. And so the designer had to ask himself some basic questions: What's going to be in the book? for what purpose will it be read? who's going to read it, and why?" That the Seligman book was to be essentially "monumental and commemorative" led the designer to a fundamental decision: For such a book it was appropriate that "the type should be of a bit larger size than would ordinarily be necessary, the leading a bit more ample, the page size a bit larger, and the margins a bit wider to show off the beautiful paper which we had specially made for this volume."

Next came decisions on typography. Here the designer's aim was what it always is: aesthetic coherence. "Every part of the book," as Stinehour says, "had to relate to every other part." The design of the basic page was the first step: size of type, leading, relationship of headings to text, initial letters, even such details as placement of the page number. Then the designer turned his attention to other parts of the book such as contents pages, appendix material, and index. Only at the end did he undertake to design the all-important title page, for that page, Stinehour explains, "grows out of the relationship of all those other things to each other." The designer did his work well, Stinehour concludes: "When you look at this book as a whole, everything relates to everything else in scale, in style, and in basic approach. One thing flows into another. And that is one of the great subtleties of bookmaking."

Stinehour's prescription for good book design is as simple, as understated, as the Northeast Kingdom he lives in: "Absolutely nothing ostentatious, nothing overdone or overblown. Everything very subtle, very quiet." In designing, if anywhere, quality bookmaking shows itself to be an art, not just a craft. "Good taste, skill, severe training": As Henry Stevens knew, they go to the essence.

Can the small quality press, with its emphasis on design, accuracy, uniqueness, survive? Is it not perhaps an endangered industrial species or at best a sentimental anachronism from an age long gone, hanging on, for the moment, only in such occasional, isolated sanctuaries as that afforded by the Northeast Kingdom? Opinions differ. Some say the signs are not propitious. Bookmaking is an industry like any other, they urge, and therefore not immune to the winds of change in an unsettled economic climate where the cult of bigness seems to beget only increasing bigness. Our mass culture, moreover seems increasingly indifferent to-or at least inured to-the standardized, massproduced products on its library as well as its supermarket shelves.

Others read the signs differently. They take longer views. Stinehour is one of these. The incontrovertible fact that small craft industries such as Stinehour Press continue to thrive, he suggests, is convincing evidence that they must be meeting a need that demonstrably cannot be met by mass production methods. Even more important, in the long perspective of history, he hypothesizes, such industries may turn out to have been the harbingers of a new mode of social and economic thought that challenges the very cult of bigness itself. He recently wrote: "Small organizations may in fact be in the forefront of a new movement toward a participatory industrial democracy, one that can serve basic human needs that are suffering so from neglect today. It is the cult of bigness that is crumbling; it is the cult of mindless work in the production of useless things that is under fire. Small groups of intelligent workers engaged in humanizing pursuits may yet be the salvation of our age."

But only, one suspects, if they continue to keep their sights high and their perspectives straight. As straight as the view downriver from Lunenburg, Vermont. Stinehour lives there; he knows all about perspectives: "The whole thing is a matter of scale. It really is."

Our luxuries and our daily bread

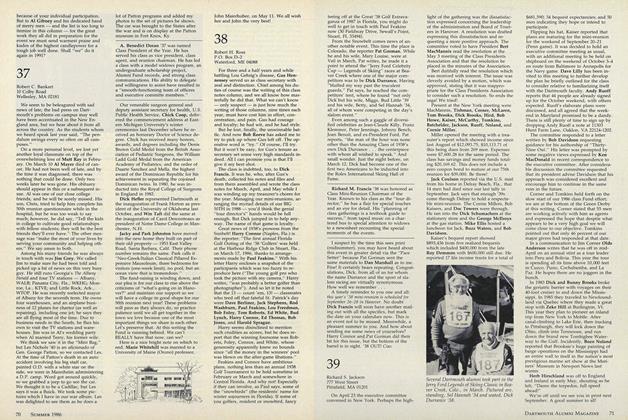

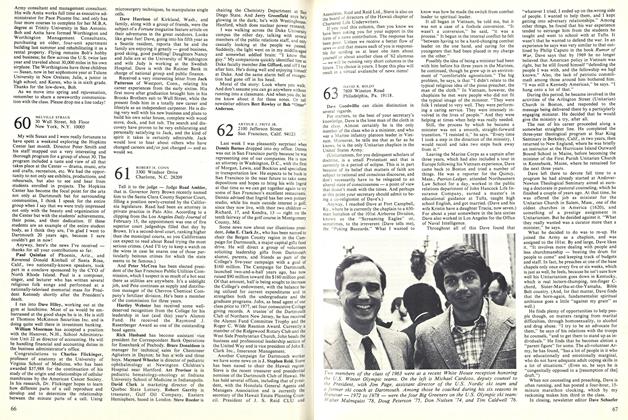

Roderick D. Stinehour '50 (right), with Harold Hugo, retired president of Meriden Gravure Company of Connecticut. Longtime friends as well as colleagues in their craft, Stinehour and Hugo personify the close collaboration of their companies in the production of many of the finest books printed in America during the last 30 years.

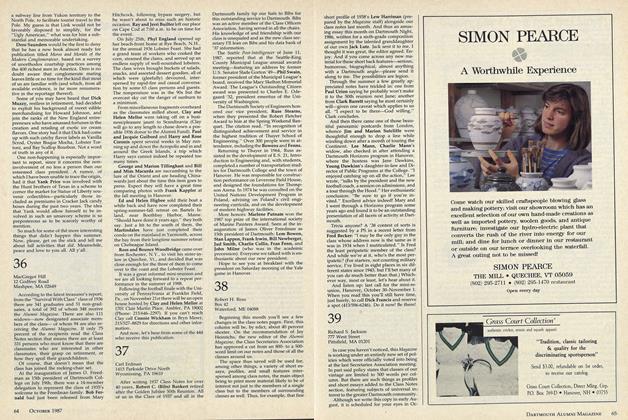

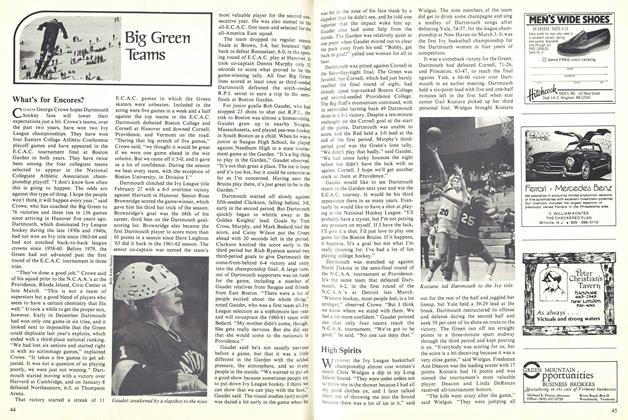

The keyboard of a monotype machine. The manuscript (left) is typed into the monotype, which transfers it to a perforated tape (top). In the second step of the process, John Melanson '54 (opposite page) operates the machine that transforms signals from the tape into hot-metal type. Then the type is locked in forms for the press.

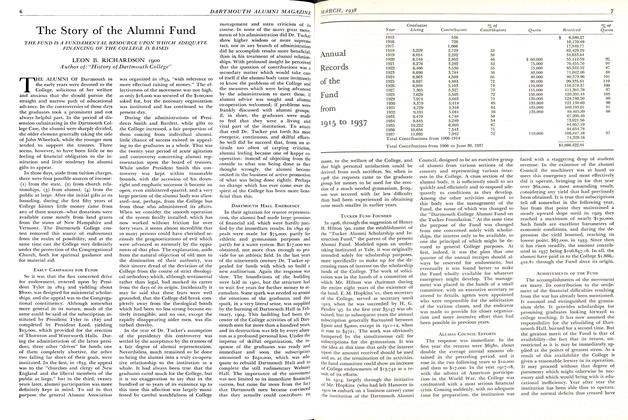

At top, John McCormack, pressroom foreman at Stinehour, locks up a form, which has been hand-set, before putting it on the bed of the press. The "shop sets" of galley proofs are clipped together and kept at Stinehour for use by the copy editor.

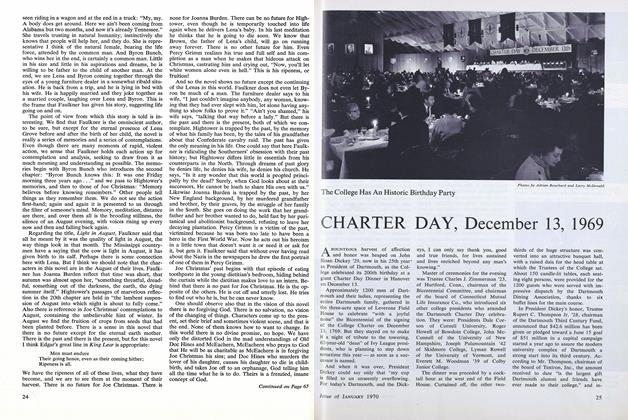

Unlike the several design, editorial, and type-setting steps that have preceded it, the actual printing of a book takes only a short time. Here, in the Stinehour pressroom, book sheets roll through a flat-bed cylinder press 16 pages to the full sheet.

"We don't just come together at the Press and then go our divergent ways. We live in a separate world, but we all live in it together." At top, the Stinehour logo.

Robert Ross '38, retired professor ofEnglish and literary historian, is bookreviews editor of the Alumni Magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

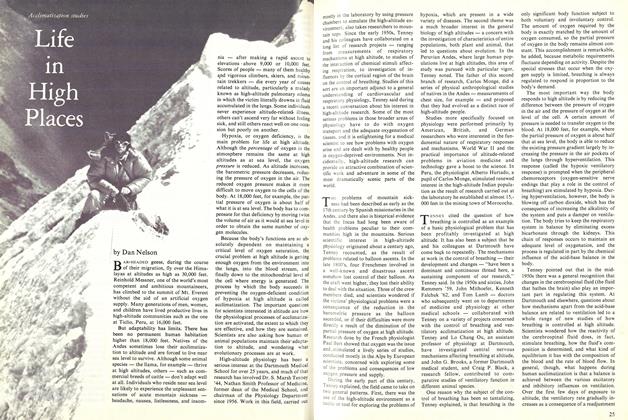

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWho in Hell Was Jeff Tesreau?

April 1980 By Edward D. Gruen '31 -

Article

ArticleAdapting to the Heights

April 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1980 By DAVID R. BOLDT -

Sports

SportsWhat's for Encores?

April 1980

Robert H. Ross

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAnnual Records of the Fund from 1916 to 1937

March 1938 -

Feature

FeatureCHARTER DAY, December 13, 1969

JANUARY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureStar Birth, Star Death, and Black Holes

February 1975 By DELO E. MOOK -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA 10-STEP PROGRAM FOR GROWING BETTER EARS

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT CHRISTGAU '62, VETERAN ROCK CRITIC -

Feature

FeatureSome People Are Good Skiers

February 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

FeatureUNDERPROMISE AND OVERDELIVER

OCTOBER 1990 By William H. Davidow '57