Year-round operation • tenure • the curriculum • salaries • faculty meetings

Dartmouth College went through an accreditation visit not long ago. We were fortunate enough to have truly distinguished educators on our accreditation committee, and it was a matter of great pride that they said to me in a personal meeting that ours is perhaps the most exciting undergraduate college they had ever visited.

However, the accreditation committee expressed one major concern. They felt that there is too much going on at Dartmouth and that as a result many faculty members feel greatly overworked and are experiencing an almost breathless pace. I share this concern. I can find no single ex- planation for this feeling, how- ever, and I worry about the scapegoat that has been selected to explain all the faculty's prob- lems.

Some of the reasons for a sense of hectic pace are happy reasons. Our students are better than ever, and good students demand more attention than aver- age students. There has also been an immense increase in the extracurricular activities of the College, most notably in the number of distinguished visitors who come to Hanover and in the cultural activities the College now offers. We all have a feeling that there are many more worthwhile events going on at Dart- mouth that we would like to attend than those we can actually get to.

I believe that a major cause for all of us feeling a hectic pace has been an increase in the complexity of society in general and in Dartmouth College in particular. Life just isn't as simple or as pleasant as it was 20 years ago. Local, state, and federal govern- ments now interfere in a vast number of areas over which we used to have control. The intrusion of the federal government has been particularly painful. Even when the federal programs are worthwhile in their purpose, the bureaucratic nightmare that accompanies them can often be unbearable.

A good example of this is affirmative action. This is a program that I have always supported strongly and one that the Dart- mouth trustees adopted before there was a federal requirement to have such a program. At least in the case of Dartmouth Col- lege, the federal programs and requirements have not contrib- uted one iota to our success in achieving our affirmative-action goals. On the other hand, the enormous amount of time that both the faculty and administra- tion must spend today on recruit- ing and on filling out endless forms is a direct result of federal regulations. All academic institu- tions live under a constant threat that any employee not hired or promoted (even for the best of reasons) can file a complaint that will bring a huge bureaucracy down upon them. Even when an institution wins the case and good institutions win most of the time it involves an enormous expenditure of effort on the part of senior officers and a large sum of money in extra legal fees. There is no way of recovering the cost of these efforts even if it is eventually determined that the complaint was totally baseless. We are also suffering from a national m'alaise; people are dis- couraged and do not readily see solutions for ever-present inter- national problems, for runaway energy costs, and for double- digit inflation that reduces our well-being. Since we cannot strike at the true causes of these problems, we tend to take it out on those nearest to us, which, in the case of an academic institution, includes taking it out on the College. (The economic malaise of Dartmouth as a whole and of the faculty in particular is discussed elsewhere in this report.) Here, the favorite scapegoats for the present sense of being overworked are the term calendar and year-round operation. These were the subject of many length) faculty meetings during the spring. Since at those meetings Iwas in the chair and therefore unable to speak to the merits of the issues, I would like to express now some of my thoughts on this subject.

About half of the present faculty has come since the start o year-round operation, and they did not know the College before the Dartmouth Plan. Only a handful of us on the faculty were here when we were still on a semester system. I keep being astounded at having one or the other of our recent developments blamed for problems that pre-date their beginning. As many of the complaints I hear are shared by our sister institutions that are neither on year-round operation nor on a term system, I have to conclude that to some extent these issues are scapegoats.

Let me try to tackle the issue of three terms vs. two semesters (ignoring year-round operation for the moment). The trade-offs are fairly clear; choosing between them is not. In a semester system the length of a given term is significantly greater, but students take more courses at the same time. In a three-term calendar terms are shorter, but you have a larger fraction of the student's attention in any given term and faculty members teach fewer courses at a time. Therefore, your preference may be strongly dictated by your discipline. When more than 20 years ago Dartmouth adopted the three-term, three-course system, the final faculty vote was two to one in favor of the new plan. Generally, the sciences and the social sciences voted in favor and the humanities were opposed.

Both systems have their advantages and their disadvantages, and we are in a somewhat dangerous situation today when many of our faculty know the disadvantages of the present system and have not experienced (as faculty) the disadvantages of a semester plan. When we made the original change, our students were tak- ing five courses a semester; that meant that they could not con- centrate very much on any one of them. I remember times when students would come up to me to say that they had four exams in one week and so they could not do any work in my course. In a highly sequential subject like mathematics that can be a disaster. Having taught under both systems, 1 know from personal ex- perience that today I can cover somewhat more material in a course and with many Jewer interruptions than I used to ex- perience under the semester system. There are those who feel that they can cover much less because the shorter calendar does not allow enough time for contemplation. I like having the attention of students for four hours a week rather than three, and I like the freedom the term system gives us to have four short classes, three longer classes, or two two-hour classes per week totally at the instructor's option. That freedom would be significantly reduced if we returned to a semester system.

Indeed, what worries me is that many arguments I have heard for a return to a semester plan are based on an assumption that we can keep all that is good about our present system and com- bine it with the advantages of a semester system. For example, many faculty members who argue for the change back to semesters avoid the issue of how many courses a faculty member would have to teach in a semester. At the time the change came we all were teaching three courses per semester. It is very difficult to teach three different subjects at the same time. To most of us it was an enormous relief to be able to teach the same six courses over three terms, two courses at a time. Although the teaching load was decreased in the sixties from six to five courses, under the semester system it would still be unavoidable that one would have to teach three courses (or course-equivalents) in one of the semesters. In the present system we teach only one course in one of the three terms, and that is of enormous importance in allow- ing free time for research. That freedom would be lost with a change to the semester plan.

I discussed this issue twice with the faculty committee on the curriculum (the Wright Committee) during its deliberations and was disappointed that the final report avoided discussing it. I suspect that many faculty members think a semester system would still allow them to teach only two courses per semester, which would reduce everyone's teaching load by 20 per cent. With the current financial problems of higher education I see no way that that goal could be achieved. Whether it could be achieved does not depend on the calendar; a four-course load would make either calendar much more attractive. Nevertheless, under any given load the number of courses taught (or studied) at a time is higher in a semester system.

Another serious disadvantage is the large reduction in our foreign-studies programs that would necessarily result from a change to semesters. Programs that are now given fall, winter, and spring would be given for only two semesters. This would certainly result in many fewer students having an opportunity to participate in one of our most popular programs. Indeed, several science departments feel that their students would be automatically eliminated from these foreign-study experiences because with only eight semesters instead of 11 terms, a student could not afford to take off a semester and still complete a highly sequential major.

The calendar is closely linked to year-round operation. When in 1971 the faculty had lengthy debates on switching to year- round operation, there was a major attempt to see whether a three-semester plan could be made to work. At that time it was concluded that it couldn't. The possible calendars for a three- semester system tend to be much less attractive than quarter calendars. While the calendar proposal of the Wright Committee is quite ingenious, the price the committee had to pay was to recommend a summer session significantly shorter than the other semesters. This would make it very difficult for the summer ses- sion to equal the others in importance, and it would create a dilemma for faculty members who have to teach the same course in the summer that a colleague has a lot more time for in another semester.

Some faculty members complain about the extra work of hav- ing to start courses three times a year and grading final exams three times. They forget that the tradeoff is that under the semester plan they would have to be reading final exam papers and term papers in three different courses all at the same time an experience not to be strongly recommended.

I have a strong sense of the divisive debate that is likely to take place this spring. The final vote of the Wright Committee was as follows: five in favor of semesters, four in favor of terms, three abstentions, and two members absent. A poll conducted by the committee indicated that the faculty is similarly split on the calendar issue. Another poll showed that students strongly prefer the present system. This is quite understandable, since students know that switching to a semester system will vastly reduce the freedom of choice they now have under the Dartmouth Plan. It will not be an easy spring. All I can hope for is that all the rele- vant facts will be brought out before the faculty takes its final vote.

Let me now turn to year-round operation. On this question the Wright Committee concluded that there is no possibility for Dartmouth College to give up year-round operation. The com- mittee is absolutely right. When in 1971 the faculty overwhelmingly voted in favor of year-round operation, I was asked this question specifically and I answered it unambiguously: The change was a one-way street. We made a commitment to a significant increase in the student body (and in the faculty) without building a huge number of new buildings. It is still true today that we cannot possibly accommodate anything like our present student body with our present plant in nine months of the year. Nevertheless, I expect a significant debate on this subject because year-round operation has contributed to the hectic feel- ing on campus. Some dire predictions have turned out to be false. It is not true that year-round operation has interfered with a sense of class spirit or that students no longer form lifelong friendships. Both the testimony of our students and the participa- tion of our young alumni in alumni affairs give eloquent testimony to the contrary. It is true that there is a great deal more moving on and off campus and that the faculty no longer has the simple rhythm of nine months of teaching and three months when everybody is off.

However, we tend to overlook that this is a different age from that of 15 years ago. Most other schools are not on year-round operation, and yet there is a great deal of movement on and off campus. One of our very distinguished sister institutions reported that in one single graduating class 40 per cent of the students had taken leaves from the institution because they did not like the lock step of traditional education. We hear of increasingly large percentages of students who take five years or longer to complete their education, and the transfer rate has increased significantly even among the most distinguished institutions. At Dartmouth we have almost no students transferring out, and the vast ma- jority of students graduate and graduate on time. I am firmly convinced that it is precisely the plan of year-round operation that has achieved this because students can take off six or even nine months at a time fulfilling an inner need and still graduate with their class. I have heard from hundreds of students that they come back from their leave terms under the Dartmouth Plan with a sense of renewal and devotion to the institution. Also, the evidence is overwhelming that the jobs Dartmouth students have during their off-terms can have a major impact on their future career plans.

Perhaps the most important consideration is that the freedom of the Dartmouth Plan is one factor that attracts able students to the College. Being like everyone else is not a good strategy for at- tracting outstanding students!

The story for the faculty is different. When I first came to Dartmouth the summer was totally free; there were no students around. Those were ideal conditions for three months of un- interrupted research and intellectual refreshment. While it is still true that faculty members teach only three out of four terms, no matter when they have their vacation term there are large numbers of students around. The Dartmouth faculty is strongly devoted to its students and will make itself available even when there is no obligation to do so. I know many faculty members whose off-terms in Hanover turned out to be almost useless for research because of the amount of time they spent with students. The Wright Committee has recommended an increase in the sab- batical program to compensate the faculty for this extra load. 1 favor an increase in this program if we can figure out how to im- plement it without a major budget impact. But I feel that a vastly more important recommendation is that faculty members protect their leave terms and that the students be made to understand the importance of this. Faculty members should refuse to serve on committees during leave terms. They should either not make themselves available to students in a term where they have no teaching obligations or limit such appointments to no more than two afternoons a week.

It would also help if the faculty stopped increasing its own load. There seems to be no end to the proliferation of faculty committees and to the increase in the number of meetings each committee has. The faculty has made regulations much more complex, thus requiring a great deal more time in enforcing regulations and in counseling students. Take one simple and not very important example: A regulation was passed that every stu- dent applying for foreign study must receive letters of recommen- dation from three faculty members. That's 2,000-3,000 letters a year that the faculty is now writing that it did not have to write a decade ago!

Let me now examine the more direct impact of year-round operation on the load that the faculty is carrying. The following table shows the increase due to year-round operation in the size of the faculty and in student enrollments.

Faculty/Student Growth1970-71 1979-80 GrowthFaculty FTE 269 318 18%Student FTE 3216 3870 2096(FTE = "Full-time equivalent")

While year-round operation enabled us to increase the student body by more than 25 per cent, course enrollments have grown only about 20 per cent because the typical student attends Dart- mouth for only three and two-thirds years (11 terms). My original target for increase in the faculty was 15 per cent, hoping that we would gain economy in the increase of size in the institu- tion. My argument was that while in some courses above a cer- tain size more sections would have to be given, in small courses one could easily take a 20 per cent increase without having to add another section. Four years ago it became clear that we were not realizing anywhere near this economy, and I had to agree to a larger-than-planned increase in the faculty.

The faculty still feels that the increase has been insufficient because in addition to the enrollment increase there has been a much larger increase in the number of majors. There one does not get a break due to the students coming for only 11 terms, since every student must complete a major. Also, we have significantly reduced the number of exchange students and replaced them with regular Dartmouth students, all of whom complete a major.

In preparing this report I have tried very hard to understand why we failed to realize the projected economy of size. I believe the answer lies in the fallowing table, which shows the distribu- tion of courses by enrollment.

Class Size (Fall of 11 and 78) Range % of Courses % of Enrollment 1-9 28 6-^ J>6l% ">28% 10-19 22^ 20-29 20 "^>39% 30-49 l9^ 50-99 l6 J>B% 100-up ll^

First of all, I must repeat an argument that I gave in my five- year report to show that distribution of courses by size looks very different to the faculty or to an outside observer than it looks to students. The middle column of the table shows the percentage of courses with various enrollments. We note that 61 per cent of all courses are small, while only 8 per cent of the courses are large. However, it is the third column that is relevant to students; it shows that the average student has 28 per cent of his or her courses in small sections, 39 per cent in medium-sized courses and 33 per cent in large courses. The explanation for the difference is very simple; a large number of small courses still ac- commodate only a small number of students.

Next, I compared these figures carefully with those from before year-round operation. I found, to my disappointment, that there has been little change in the percentages in the first three categories of class size. That is, we did not realize an economy of scale. What happened is that a sufficient number of new courses have been added to wipe out the potential gains. Secondly, I noted a small but significant change in the last three categories. The percentage of large lecture courses in the final category has dropped from 5 per cent to 3 per cent, and there is a correspond- ing increase in courses in the 30-49 range. This is a change that significantly contributes to the faculty load and is of little or no benefit to students. If we have 20 fewer large lecture sections, they are replaced by 60 classes in the intermediate range. The faculty must teach 40 additional courses, and that intermediate range is perhaps the most inefficient range to operate in. For ex- ample, this term I am teaching an upper-level mathematics course that has 47 students in it. That is one of my least favorite sizes. If I have 25 or fewer students I feel that I can give them in- dividual attention and get to know all of them. If I have 40 or more students I have little option but to conduct the course as a lecture course with the same amount of effort I could do an equally good job with 120 students. Indeed, I would prefer the latter because it would entitle me to a large lecture room with first-rate blackboard space and visibility and with an atmosphere that lends itself much better to lecturing. While as an un- dergraduate I loved very small courses, some of my most inspir- ing courses were in large lectures with superb lecturers.

As I look at the above table, my greatest worry concerns the 28 per cent of the courses that have fewer than ten students in them. While some such courses are unavoidable because of the desire to give advanced courses in all disciplines, I cannot excuse such a large percentage of tiny courses. It is in this area that we could make a significant cut. If the cut were large enough, it could simultaneously result in financial savings to the institution and reduce the load of the faculty.

A further major contributor to a sense of being overworked are the freshman requirements voted by the faculty. Freshman English, the freshman seminars, and elementary language teaching are an enormous burden. While all of these re- quirements are desirable, they represent a totally dispropor- tionate amount of faculty time, and most of this burden is borne by the Humanities Division. The Humanities Division carries 28 per cent of student enrollment and" less than 28 per cent of the majors, but it has 40 per cent of the total faculty full-time equivalents. The reason why this division has a disproportionate share of the faculty and yet feels overworked is the way members handle their freshman load. In the Science Division freshman sections represent 16 per cent of the total, in the Social Sciences 27 per cent, while in the Humanities it is a staggering 43 per cent of the teaching load! This is because the faculty has required a freshman composition course, freshman seminars, and language teaching, and the Humanities Division is convinced that these cannot be taught in other than small sections. While one can always argue about how small small must be, it is certainly true that these courses cannot be taught in large lecture sections.

The existence of these courses also has a multiplier effect. There is a limit on how many freshman composition courses or elementary language courses you can ask a distinguished member of the faculty to teach. In both English and several language departments there is an inflation of upperclass courses to allow faculty members to have a balanced teaching load. The alternative would be to hire a large number of faculty members who specialized in freshman courses, a solution that would be contrary to the spirit of Dartmouth College.

If one division commands more than its quota of faculty members, some other division must suffer. At the present time, this is the Social Sciences Division, which carries 31 per cent of the total enrollment and 49 per cent of the majors but has only 28 per cent of the faculty.

There is one final factor that I must mention as contributing significantly to a sense of being overworked. In my opinion we have gone much too far in the use of lecturers, visiting faculty, and adjunct faculty members in the past decade. Fourteen years ago there were 28 individuals in these categories; at the present time there are 133 (although they represent only 11.5 per cent of the full-time equivalents). The big growth has been in visitors and adjunct faculty. Some of these are long-time Dartmouth employees and some may represent special talent available in the other faculties or in the region. A certain level of visitors and dis- tinguished outsiders who do part-time teaching is highly desirable for the institution because it provides a greater diversity of faculty to our student body. "Outside" faculty members rarely carry their full share of the teaching load, however, and they do not carry their share of departmental and institutional non- teaching assignments. In addition, the continual necessity of recruiting these individuals adds to the burden on departments. If the current budget problems force us to make a modest cut in the size of the faculty, I would favor making it in this category. Indeed, I would go further than that and convert some full-time equivalents that are now spread out among large numbers of in- dividuals to regular faculty positions. I am certain that this will contribute to the stability of the institution and reduce the sense of hectic pace on the part of the faculty.

c ince my five-year report contained a very extensive I discussion on the issue of tenure, I will only add a brief update. The stresses created by a limited number of tenure slots and outstanding junior faculty competing for them have continued. As the national job market for college faculty members has worsened, the anxiety of young faculty members that they will be forced out of the academic profession has become even greater. I believe that the plan I described five years ago for charting a reasonable middle course between the needs of the junior faculty and the best interests of the institution has been quite successful. We continue to grant tenure to about the same percentage of the junior faculty as we did a decade ago; very few other institutions are able to make that statement. No truly outstanding candidate is ever denied tenure because of an artificial quota. But the competition is extremely great, and some faculty members whose qualifications would have earned them tenure in the sixties today fail to qualify.

A serious complication has been added by federal legislation that extends the retirement age to 70. While higher education has a temporary exemption, this will expire in 1982. I was one of the most outspoken critics of this particular legislation as it applied to tenured faculty members. Whatever sense it may make in other segments of the economy, it does not make sense in higher education, which is in a unique position. At a time when educational institutions nationally will face extremely small numbers of retirements, when expansion is out of the question, and when we are trying to counteract historic injustices by recruiting women and minorities in larger numbers into our tenured ranks, legislation that postpones retirement by up to five years will significantly hurt the quality of our institutions.

I am not arguing that many faculty members aren't fully qualified to continue beyond age 65. The College has always made exceptions, and many of our faculty members have ob- tained appointments at other distinguished institutions after their retirement from Dartmouth. But an automatic extension of the retirement age for all our tenured faculty members, the overwhelming majority of whom are white males, has a dis astrous effect on junior faculty members in general and on affir mative action in particular. While the law will still allow firing an individual for "cause," for a tenured faculty member this is horrendously difficult and painful process. I am sure that in stitutions will be extremely reluctant to invoke this clause for faculty members who have loyally served the institution for 3o years or longer, no matter how justified the action might be

We have therefore had to readjust our thinking, and we win probably opt for allowing the ratio of faculty on tenure to rise higher than is normally healthy for an institution. This is the only way I see to avoid demoralizing our junior faculty. Nor would it be healthy for the institution to go through a decade with ex- tremely few promotions to the tenured ranks. It would create an age imbalance for which future students would pay a heavy price

This is an outstanding example of the increasing intrusion of the federal government and of the inability of legislators to dis- tinguish between the problems of a factory and those of a univer- sity.

M Mne of the sad effects of having entered "steady V state" and at the same time facing serious finan- rial problems is that the chances for major changes in the curriculum are severely limited. Nevertheless, even under these difficult circumstances we have made some significant progress. I will comment on several examples in the section "The Future as Past."

The faculty has just been engaged in an intensive committee study of the curriculum requirements of the College. While a few of the recommendations of the Wright Committee have passed, many failed to muster a vote of the majority of the faculty. We will see a few good improvements, but I sense an overwhelming consensus that the faculty is happy with the curriculum as a whole and with the requirements that we impose on our students. While one of our sister institutions received an enormous amount of national publicity for its return to a "core curriculum," it is hard to get similar national recognition for the fact that Dart- mouth had never abandoned its fundamental requirements. We still have the requirement of freshman English, of a writing course, a foreign language, 12 courses distributed in three different divisions outside the student's major, and strong re- quirements for completing a major. What the faculty has done in its debate of the Wright Committee recommendations is essen- tially to reaffirm its faith in these requirements. That you have never read in the papers about these developments is simply evidence of the fact that the reformed sinner is much better publicity material than one who has never sinned at all.

f B bout once every other year the dean of the faculty and I make an attempt (usually unsuccessful) to ~JBL separate fact from fiction concerning faculty salaries. Naturally, the economic welfare of the faculty is an issue of enormous importance. It is also a very emotional one. I would like to make one more serious attempt to separate sense from nonsense.

College faculty members as a profession have never been par- ticularly well paid. On the average, businessmen, lawyers, and doctors make more money than faculty members even though their training is no longer, and often shorter, than that required of a college faculty member. Also, the high end of the salary scale in these three professions is much higher than that for academic faculties. An individual does not choose to become a faculty member in order to make a great deal of money. One is motivated by a love of teaching and by a desire to have time for research and to do the research one chooses for oneself. One trades off economic benefits for a nine-month teaching year and for periodic sabbaticals. One can tolerate significantly lower salaries only if one loves teaching.

While these factors motivate faculty to accept a lower pay scale than other professions offer, there is a limit to what is tolerable. When I first entered the teaching profession 30 years ago, academic salaries were miserable. Dartmouth salaries were poor even compared to those of comparable institutions. During the late fifties and the sixties when there was a major expansion of higher education it was an extremely affluent period for these institutions the relative economic status of the faculty improved significantly. I do not mean that professors caught up with doctors, lawyers, and businessmen, but at least they could aspire to an income on which they could live in comfort and dignity. Under John Dickey's leadership, improvement of the Dartmouth faculty was spectacular. During the early portion of my administration I completed his program to catch up with the salaries of our sister institutions, but during the last few years faculties, both here and nationally, have again lost ground.

In periods of runaway inflation, academic institutions cannot increase their sources of revenue in proportion and therefore are unable to give salary increases that keep up with inflation. The best we could do was to make sure that we did not lose ground relative to our immediate competition.

While I would be the first one to argue that the plight of all academic faculties in the late seventies has been most unfortunate and must be reversed when economic conditions turn more favorable I strongly deny persistent stories that Dartmouth has lost ground with respect to its sister institutions. There are three major factors that lead some faculty members (and TheDartmouth) to present Dartmouth College in the most un- favorable possible light.

The basis for all the comparisons are numbers reported to the American Association of University Professors, which annually compiles average salary and compensation figures for faculties throughout the United States. The first unfair comparison is to compare us to large universities. Since the salaries reported are for the entire faculty of an institution (excluding only medical schools), at large universities a major fraction of the salaries reported includes the professional schools that traditionally have a higher salary scale. There is no way of separating the salaries of the arts and sciences faculty from the overall figures, so the salaries we pay to the largest portion of our faculty is unfairly compared to those being paid in law schools and business schools.

Secondly, those who wish to make Dartmouth look as bad as possible compare salaries and not total compensation. Because Dartmouth College happens to have one of the best fringe-benefit programs among the leading institutions in the country, this is totally unfair. The largest difference between our fringe benefits and those of other institutions is in the retirement program. For example, to faculty members above age 40 the College con- tributes to the retirement plan 16 per cent of base salary, with no contribution required from the individual. At most comparable institutions, the institutional contribution might be 10 per cent with 6 per cent coming out of the faculty member's pocket. This single item means that in terms of real take-home pay our com- pensation is understated by 6 per cent if only salary figures are reported. That 6 per cent usually makes the difference between our salaries looking reasonable or not.

The faculty as a whole understands this very well about Dart- mouth and has periodically fought for increases in fringe benefits as a trade-off for salary increases. The most recent example has been a significant improvement in the medical coverage available to faculty and administrative officers, a change that came about at the request of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. There were two important advantages to making this move. First of all, one can obtain reasonable medical insurance only as part of a group. Secondly, when the College carries a larger burden of medical ex- penses through the insurance program, this benefit is provided in a non-taxable form. It was clearly understood by the faculty that this additional medical benefit would be traded off dollar for dollar for a somewhat smaller increase in cash salary, and that made it even more unfair to compare salaries rather than com- pensation.

Thirdly, we are hit by comparisons of average faculty salary (or compensation) where the average is taken over the entire faculty. To explain why this is extremely unfair to Dartmouth, I would like to give a concrete example.

Compensation Comparison (In Thousands of Dollars) RANK DARTMOUTH COLLEGE X % in % in Compens. Rank Compens. Rank Professor $38.9 41% $38.3 60% Assoc. Professor 26.4 17 26.0 21 Asst. Professor 20.5 42 20.2 19 "AVERAGE" $29.0 $32.3

This table shows the actual comparison in compensation, rank by rank, with one of our sister institutions. As can be seen, the Dartmouth compensation is a few hundred dollars higher for each rank than it is at college X. However, when one computes the average compensation of a faculty member, theirs is more than $3,000 higher than ours. Since we beat them in every single rank, this is not due to having a poor salary scale at Dartmouth as spokesmen for college X will readily admit. It is due to the fact that we have a much younger faculty! It was this calculation (of average salaries) that led to a banner headline announcing that Dartmouth has the lowest salaries in the Ivy League.

Just how do we compare? We carefully watch our average compensation by rank as compared with a group of sister in- stitutions that are in most ways comparable with us. All of these are institutions of the very highest quality but ones whose salary scale is not distorted by the presence of large professional schools. We are well within the range of salaries at these in- stitutions in each rank. Frankly, I would feel happier if all our salaries were about a thousand dollars higher, and each year we have to make a maximum effort simply not to lose our relative position. It is certainly not true that our salaries are out of line with comparable salaries at comparable institutions. We also have other evidence that our salaries are competitive, namely in the competition for star faculty members with other institutions. Our record in this decade has on balance been heavily in Dart- mouth's favor. We find that if we want a faculty member badly enough we can attract him or her without having to distort our compensation scale. Those faculty members we have lost generally left for reasons other than financial; usually the other institution offered them a professional opportunity that was not available at Dartmouth.

I cannot resist one final remark on Dartmouth's salaries. TheDartmouth editorialized that even one of our sister institutions that has reported serious financial problems pays much higher salaries than Dartmouth. The paper asked how can they possibly do it? (The implication was that the Dartmouth administration does not care about the financial welfare of its faculty.) First of all, that institution happens to be one with large professional schools, which makes the salaries appear much better. There is an even deeper reason. Salaries are reported only for faculty members in the regular ranks. Nowhere does the A.A.U.P. take into account what fraction of undergraduate teaching is done by graduate students, who represent cheap labor. If a significant amount of undergraduate teaching is. done by graduate students, as is true at that particular institution, a larger portion of the in- structional budget is left over for the regular faculty. The only ones who suffer are the students. It is expensive to have un- dergraduate courses taught by the regular faculty, but that is a fundamental commitment of Dartmouth College that we will not give up no matter how much money we could save.

/n any academic institution worth that name the faculty plays a major role in the decision-making process. Theoretically, a board of trustees can always overrule the faculty, but a good board will use this power sparingly.

Any short statement as to the precise powers of the faculty is likely to be misleading. A rough rule of thumb at Dartmouth is that in matters of the curriculum and in matters of how the faculty conducts its own business the Board of Trustees will usually defer to the faculty. The senior faculty also has the primary responsibility for tenure decisions. In other matters, votes of the faculty are only advisory to the trustees. There ob- viously are exceptions even to this rule of thumb. If the faculty makes a major recommendation within an area that is clearly its prerogative, but it has enormous financial implications for the in- stitution, the trustees must make a decision as to whether the plan is financially feasible. Even on a purely curricular issue, if the board felt that the faculty was distorting the nature of the in- stitution, it could overrule the faculty. It is hard to give an actual example of that because to the best of my knowledge it has never happened at Dartmouth. But if a series of curricular recommen- dations would change the undergraduate college to a vocational school (something the Dartmouth faculty would never recommend!), the board would have an obligation to veto the faculty recommendation. In other areas, whether they deal with admissions policy or the nature of the Dartmouth fraternities, the trustees will listen very carefully to the recommendations of the faculty and consider them an extremely important contribution to their own decision-making process but they will reach their own conclusions.

There is considerable fascination about the nature of faculty meetings. There are many legends about faculty meetings on a variety of campuses (some true, some false), and an endless number of jokes circulate. I thought it might be of interest to the reader of this report if I gave my own impression of faculty meetings in the 1970s as well as described my own role in these meetings.

The faculty conducts the bulk of its business through an elaborate structure of committees. By the constitution of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, however, all power ultimately rests in meetings of the full faculty. There are roughly 300 members of the faculty in the regular ranks (i.e., excluding visiting ap- pointments, adjunct appointments, etc.), and all of them have a right to vote in faculty meetings. In addition there are a small number of administrative officers whose input into these meetings is crucial, and they are designated voting members of the faculty. Given such a large potential pool of votes, there has been a great deal of comment on the fact that the total number of votes tallied rarely exceeds 100 even on crucial issues. The reasons for this are quite complex.

First of all, in any given term a significant fraction of the faculty is on leave. Since the College operates four terms a year and each faculty member teaches only three terms, on the average a quarter of the faculty is on leave in a given term. One must also take into account those faculty members who are on sabbatical. Then one must add (or, rather, subtract) those faculty members who at any given time are teaching but not on the Dart- mouth campus the faculty who staff our off-campus programs (most importantly the overseas language programs).

The next most important factor is that there is a significant number of faculty members who dislike faculty meetings and simply won't attend. This was as true 25 years ago as it is today. Attending and voting in a faculty meeting is a faculty privilege, not an obligation. There is a group of faculty members who will on principle, never attend. There is a much larger group that will attend only very rarely, when the agenda of the meeting contains a topic of considerable concern to them.

The next most important factor is a group of faculty members who are currently teaching but happen to be away from the cam- pus on a given day. Any faculty member active in his or her profession must attend professional meetings and is periodically invited to give lectures at other institutions. They may also be serving on regional or national committees representing their profession. Many faculty members also travel to speak to alumni clubs. In addition, it is impossible to call a faculty meeting at any time when some faculty members do not have conflicting obligations on campus. The Dartmouth campus is teeming with activity, and even in the late afternoon there are laboratories to be staffed, plays that are in production, distinguished visitors or candidates for academic positions who have to be escorted, etc. 1 therefore conclude that the presence of 150 voting members would constitute superb attendance at a faculty meeting. However, I do not recall an attendance that large since the debates on coeducation and year-round education early in the decade.

In spite of all the reasons explained above, I must say that re- cent attendance at faculty meetings has been less good than in an earlier age. I believe there are two primary reasons for this. One is that the faculty is noticeably busier than it was in the past (a subject discussed above). The second is that while many of the issues debated have been highly controversial and even emotional, we have not had a large number of issues that the ma- jority of the faculty considers to be "very big issues."

I am happy to report that since I wrote the above section there has been a dramatic increase in attendance at faculty meetings. The debates on the recommendations of the Wright Committee have been extremely well attended. It is indeed good to know that it is a debate on the fundamentals of the curriculum that will at- tract record attendance.

What happens at a typical faculty meeting? First of all, in addi- tion to the space reserved for the faculty, there is a carefully con- trolled section available for visitors.* The meeting is called to dis- cuss one specific issue, or, on occasion, two or three issues. A meeting will last from two to two and a half hours, most of which is devoted to open debate on the issue before us. It is important to remember that all of us who are faculty members make our living through the spoken word, and debates at faculty meetings tend to be extremely eloquent and sometimes quite heated. There are many jokes about the length of such speeches, one of which is that all faculty members are used to teaching 50-minute classes and therefore can never give a speech of less than 50 minutes. In mv experience, extremely lengthy speeches are the exception. Precisely because professors have trained themselves to present complex materials succinctly to students, they are able to present important arguments in a reasonable length of time. Still, when you have 100 people present, all of whom are eloquent speakers and many of whom have very strong feelings on a given subject, the total length of the debate can be great. It is one of the strengths of the faculty that it is able to look at an issue from a large number of points of view and consider many ramifications. It does, however, tend to make the debates both more sophisticated and more complex than those typical in a legislative body.

Secondly, the faculty members are very good listeners. One always hears stories of legislative bodies where there is almost no one present when key speeches are given. The speeches are given for the published transcripts of the meeting, which may or may not be read by fellow legislators. There is practically no walking in and out in faculty meetings. The only exceptions are late arrivals due to a campus obliga- tion and departures when a meet- ing goes well past the dinner hour.

By the constitution of the faculty, the president chairs fac- ulty meetings. If he is not present or if he steps down from the chair, there is an elected member of the faculty who chairs the meeting. Since I feel that chairing our faculty meetings is one of my most important obligations, I have missed only about one faculty meeting a year. I have taken advantage of the privilege of stepping down from the chair in order to speak only on the rarest of occasions, for reasons I shall discuss.

I feel that my principal role as chairman of the meetings is to help the faculty reach its own consensus. I have been careful to preserve the prerogatives of the president of the College, but I do not feel that occasions when I am in the chair at a faculty meeting are the right occasions on which to exercise those prerogatives. I try, whenever possible, to give my thoughts on a certain matter when it is still in the hands of a faculty committee. If the faculty should reach a decision I feel to be highly adverse to the best in- terests of the institution (a truly exceptional occurrence in my 25 years experience as a member of the faculty), I still have a recourse by recommending to the Board of Trustees that it not accept the faculty vote. My principal role at a faculty meeting is as an expediter and one who maintains order. As one faculty member has said to me, my principal role in that context is to prevent chaos.

The membership of a faculty meeting represents an excep- tionally intelligent decision-making body and a verbally skilled group. However, the meetings must be run strictly according to Robert s Rules of Order, and while there is a small group among the faculty that is truly skilled in parliamentary matters, the ma- jority of the faculty has only a vague idea about the intricacies of Robert s Rules. 1 have found that one of the most useful roles that I can play is to explain periodically what we are doing. For example, a main motion may have been introduced two hours ago, an amendment to the main motion introduced an hour and a half ago, and a substitute for the amendment introduced three- quarters of an hour ago but defeated 15 minutes later, at which point another substitute for the original amendment to the main motion was introduced. At this point it is quite likely that the majority of those present are not at all clear what it is that they are supposed to be debating or what they are voting on. It is the responsibility of the chair to state the motion clearly before it is put to a vote. However, this rule narrowly interpreted will not serve the needs of the assembly. What the members of the faculty need to know is not only the precise wording of a motion but what the effect of a yes or no vote would be particularly when there is a main motion, an amendment, and a substitute to the amendment before us.

I have learned in the past decade that knowing when to bend the rules is as important as knowing how to enforce them. I have tried to be scrupulous in never bending the rules in order to achieve my own purposes but only in order to expedite that which the faculty is trying to achieve. I have not hesitated to make suggestions on how to get out of a parliamentary snare and thus have helped many faculty members to get their proposals considered, and I have done this in just as many cases where I dis- agreed with the faculty member as in cases where I agreed with the proposal. Perhaps the hardest judgment call is when to urge the faculty to bring a matter to a vote. One must be very careful to make sure the right of a minor- ity is not violated by early clos- ing off of debate. On some issues even two hours of debate may be an early closing. When the chair recognizes that an over- whelming consensus seems to have developed, however, he can help the faculty by urging a vote to prevent what is by now a hopelessly outnumbered group from filibustering the issue.

I have two other pieces of advice for anyone who has to chair a faculty meeting. Some parliamentary situations can only be resolved by a ruling from the chair. Often the chair is quite uncer- tain as to what the correct ruling is. The worst mistake that can be made under these circumstances is to avoid making a ruling. That's a cop-out! The chair should make a clear ruling and then allow (on occasion encourage) an appeal on the ruling of the chair. In that way the matter is promptly put to a vote of the assembly and resolved. Otherwise, chaos can develop. My second piece of advice is that as discussions become enormously heated and tempers rise, a light remark thrown in by the chairman can significantly ease tension. (I suspect that some of my best friends who are reading this will mentally translate "light remark" into "bad joke." So be it.)

In the past decade my role as chairman of the faculty has been one of the most challenging ones. I must confess it is also a role that I have thoroughly enjoyed.

Varujan Boghosian, professor of art and assemblage artist.

Professor William Cook, English and Afro-American Studies.

Tamara Northern, curator of anthropology, with Nigerian work

*For a good account as to how faculty meetings were opened to all members of the Dartmouth community, most importantly including students, see /'5 Different at Dartmouth, Jean A. Kemeny, Stephen Greene Press, 1979.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Alumni Relations

MAY 1968 -

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38 -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

NOVEMBER 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR NAME INTO THE GUINNESS BOOK OF WORLD RECORDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By LARRY OLMSTED, MALS '06 -

Feature

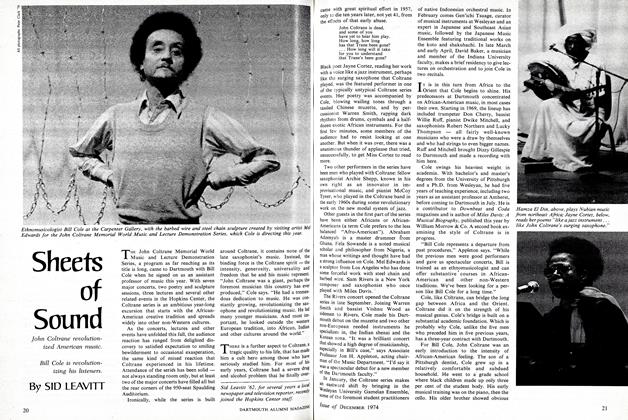

FeatureSheets of Sound

December 1974 By SID LEAVITT