Babes in Peepland

THE Times Square district of New York on a hot summer's night, 1980: The air is heavy with humidity and the smell of human sweat, the blaze of the streetlights blots out the sky, and as we push through the swelling crowds toward the neon of 42nd Street the evening takes on the quality of hallucination. By "we" I mean a dozen or so people on one of the twice weekly tours of "girlie" shows, peep shows, and porn shops conducted by a feminist group called Women Against Pornography. Male and female, ranging in age from around 20 to near 60 and dressed in everything from jeans to polyester pant suits to skirts and nylons, we are an eclectic and awkward group, one that must strike passersby as odd.

Odd and out of place is how we feel. The disco music that seems to throb from every open doorway assaults the ears, a statuesque transvestite in spike heels teeters by, drug peddlers hiss out promises of "coke . . . grass. . . speed . . . twoies [Tuinals]," a Latino couple and their two small children hurry to catch the opening scenes of "Dirty Susan," and a man in a Brooks Brothers suit, his hands in his pockets and his eyes on his well-polished wingtips, scurries out of one of the porn shops, nearly knocking some of us over in the process. As we enter Show World, our first stop, the man behind the magazine counter is yelling at a customer. "If you bend them magazines, I can't sell 'em," he shouts. "But I's gotta sell 'em anyways, so youse better not bend 'em." Sheepishly, the customer puts the magazines back in the rack, and with a shiver I notice that one is called Beauties inBondage, another Foxy and Fettered.

Later in the evening, we run into trouble at Peepland when the bouncer informs us that women aren't allowed in and then goes on to suggest that we really don't want to see what goes on in Peepland anyway, "because youse only get upset." We tell him he's wrong, that we do want to see, and we also inform him that it's a violation of Section 296 of New York State's Human Rights Law to keep us out. At this, the bouncer suddenly pretends he's gone deaf, and so we return to the street, where we find four uniformed policemen. The cops come back to Peepland with us, and when they show the bouncer the copy of the law we've remembered to bring along he says, "Look, we really don' wanna do nothin' il- legal here, it's just that women, they always make a big mess!" Even the cops laugh at this, but they accompany us into Peepland and nervously make jokes as we check out the enclosed and frequently disinfected booths where a quarter will get you a private showing of any one of a wide variety of minute-long pornographic films.

The films feature mostly violence, bestiality, incest, and other acts traditionally held perverse. After seeing a few we all start muttering words like "pathetic," "revolting," and "moronic," and, with the cops still in tow, head upstairs to see the nude dancers. On our way we pass a black Woman whose job is to sit naked in a glass booth and, for a dollar, do anything a customer requests. She has huge scars on her stomach and a glazed look in her eyes, and as we walk by the glass booth in which she awaits another dollar one of my companions grabs my arm with a hand grown clammy cold in the heat and whispers, "What kind of country is this where real live women can be bought, and bought for only a buck?"

I went to Times Square this summer principally because I had an assignment from Family Circle to write an article called "What Women Should Know About Pornography." I say principally because I went for other reasons as well. Among these was the secret hope that a trip to Times Square would help me comprehend the facts about pornography which, from months of research, I already knew. From the California Department of Justice and Forbes magazine, for example, I already knew that in 1977, the most recent year for which figures are available, the pornography industry in this country took in more than $4 billion, or more money than the conventional movie and music industries combined. From the F.B.I. I knew that whereas in 1970 there were fewer than 15 hundred "adult bookstores," or porn shops, in the United States, by last year there were nearly 20 thousand, and that this increase had recently caused the pornography industry's trade paper, TheAdult Business Report, to boast: "In 1979 there were, in fact, three to four times as many adult bookstores in the United States as McDonald's restaurants."

From the F.B.I. I knew, too, that 75 per cent of these "adult bookstores" have peep shows, that videotapes of hard-core porn films for home viewing are outselling tapes of Hollywood movies by a margin of three to one, and that three million Americans attend porn movies in theaters each week. From estimates provided by both the F.B.I, and the industry itself, I knew as well that more than 400 different pornography magazines are being published in the U.S. today, and as many as 30 million people purchase them regularly. These are just some of the facts about pornography in this country today, and I went to Times Square this summer because I knew them yet still couldn't quite believe them.

I went to Times Square also because in the past few years I've started to suspect that we Americans as a society may be heading for big trouble. A variety of trends in popular culture have led to this sus- picion, among them trends in magazine publishing, an area to which I as a jour- nalist am particularly attuned. During the past ten years, the few remaining magazines of ideas among them Harper's, The Atlantic, Saturday Review, and the short-lived Politicks have found it harder and harder to attract readers and ad revenues; at this writing, in fact, Harper's is bankrupt and out of business. During the same time that magazines of ideas have increased difficulty staying afloat, however, a slew of relatively mindless magazines like People and Self, along with more than 400 pornography magazines, have not only proliferated but prospered. Does this, I wonder, mean something? In short, does pornography's popularity tell us something perhaps something important about ourselves? These, I think, are questions that should be of concern to anyone who cares about the state and future of American culture, and I went to Times Square this summer because it seemed the obvious place to start looking for some answers.

PORNOGRAPHY, it is often said, is impossible to define. Viewing pornography as a legal term, a legal term that historically has been seen as synonymous with words like bad, harmful, and obscene and which also has been tied inextricably to the attempt to ban, the difficulty of definition proves true enough. Prior to the publication of such landmark literary works as Ulysses and LadyChatterley's Lover, the prevailing cultural opinion in this country was that explicit sex and four-letter words were bad and obscene in themselves, and the prevailing legal opinion was that the First Amend- ment did not protect works deemed bad or obscene. With Ulysses and other sexually explicit literary works, however, these opinions began to change, and from the 1930s through the 1960s the U.S. courts continually tried to come up with a foolproof formula for determining what is pornographic, meaning what is bad and therefore to be banned. Finally, in 1974, the U.S. Supreme Court gave up on por nography altogether, throwing decisions about what should be banned back to local communities. Pornography is bad and it probably should be banned, the Supreme Court in essence stated, but we don't want anything to do with it. The high court's position was perhaps best summed up by Justice Potter Stewart, who said of pornography, "I can't define it, but I know it when I see it."

Had Stewart and his colleagues been asking simply "What is pornography?" rather than "What is bad and therefore in need of banning?" perhaps pornography as a term would not be so elusive. The fact is, pornography as an etymological term, if not as a legal term, can be defined, and relatively easily. As a glance at any dictionary reveals, pornography is material intended to provide sexual excitement. This is not to say pornography is either good or bad, it's simply to say what it is. Certainly, some passages in Ulysses might strike some people as titillating, but that doesn't mean they are pornographic because effect doesn't necessarily imply intent. Even if certain passages in Ulysses were intended to be arousing, it still doesn't follow that the entire work is pornographic or that such passages are bad. Conversely, some people might not find the photographs of nude women in Playboy arousing. Nonetheless, that's what they're intended to be and so, according to the dictionary, such pictures are pornographic. But to say Playboy photographs are pornographic is not to say they are bad. Nor is it to suggest they be banned.

"The function of pornography," a recent Hustler article claims, "is simply to get people off." If it were clear that this (the intended) function of pornography were its only function, there would probably be little controversy over pornography in this country today. After all, we as a culture have arrived at a point where sexual pleasure for men and women alike is considered healthy and desirable. Yet, it is not at all clear that pornography's only function is to provide sexual pleasure, and it is over the fuzzy issue of pornography's other functions that questions and controversy arise.

To understand why there is a contro- versy over porn in this country today, it's necessary to take a look at the movies, books, magazines, and videotapes that are bringing in $4 billion a year. To do so is to see that, as pornography has become more available, popular, and profitable during the past decade, its content has changed considerably. With the buying public growing accustomed to and perhaps bored by simple nudity and the depiction of conventional sexual acts, the pornography industry has come up with ever newer and unusual ways of providing sexual excitement. As a result, much of the pornography being produced in the U.S. today is not about plain sex but sex laced with violence and kinky toys (e.g., whips) and kinky characters (e.g., supposed, nuns). And, in a rapidly growing number of cases, pornography is not about men and women, but men and children.

The fact is, the bulk of the pornography being sold in this country's nearly 20,000 "adult bookstores" is hard-core, and its most common themes are incest, rape, gang rape, humiliation via urination and defecation ("water sports"), child molestation, bestiality, bondage, battery, mutilation, dismemberment and even, as in the case of the film Snuff, the outright murder of women. A further fact is that these themes are no longer entirely confined to hard-core porn. Drugstore-variety magazines like Knave, Oui, and Chic frequently feature violence, and the best- selling and so-called soft-core Hustler has run photographs of women in bondage and dismembered female bodies. Record albums and many clothing and cosmetic advertisements also play on the violence- against-women theme, and relatively tame porn magazines like Penthouse and Playboy two magazines which reach more men than Time, Newsweek, and Sports Illustrated are not above running cartoons that make light of rape, battery, and child molestation.

The changing trends in hard- and soft- core pornography have caused many to suspect that, contrary to what Hustler claims, pornography's function is not "simply to get people off." Many in the field of psychology, for example, believe that exposure to pornography desensitizes males to traditional taboos, and may make acts like child molestation and rape seem attractive and even hip. Others in psychology, and sociology and criminology as well, go further, claiming that pornography actually leads to higher levels of aggression in males and contributes to sex crimes. Feminists, too, make this claim, and to it they add the charge that pornography is political propaganda whose function, among others, is to dehumanize women and children. Members of such organizations as the National Federation For Decency also believe pornography is dehumanizing, but they argue that it dehumanizes everyone, men as well as women and children. Still others claim that pornography's main function is to depersonalize and debase sex itself. D. H. Lawrence was one of the earliest to argue this position; in his 1930 book, Pornography and Obscenity, Lawrence, though a victim of censorship himself, advocated "rigorous" censorship of pornography and declared, "Pornography is the attempt to insult sex, to do dirt on it."

Whether or not one agrees with any or all of these claims, most thinking people probably would concede that pornography does have some effects beyond the immediate one of sexual arousal. As New York Law School Professor Ernest van den Haag observed in a recent issue of Policy Review: "Some people argue that pornography has no actual influence. This seems unpersuasive. Literature from the Bible to Karl Marx to Hitler's MeinKampf— does influence people's attitudes and actions, as do all communications."

Even if pornography could be proven to be political propaganda that leads to violence, however, the prevailing opinion among legal scholars today is that censorship would still be unconstitutional. In the words of Harvard Law Professor Alan Dershowitz, "Protection for propaganda is' the core of the First Amendment. The First Amendment was intended to protect incitement to violence. Marx, Jefferson and Samuel Adams incited to violence."

To me, one of the most perplexing questions raised by pornography is not just what it is, what it does or what should be done about it, but simply why it is, and why it's so popular in this country today. It is true, of course, that pornography in Western culture has existed for thousands of years, as the erotic frescoes of Pompeii so well illustrate. It is equally true that for most of history pornography was the plaything of the literate elite, and that only within the past ten years has it become one of the dominant elements of mass culture. Why, I wonder, is this so?

On the surface, the answer to this question appears obvious: The comparatively recent rise in pornography owes primarily to changes in technology and legal attitudes. It has only been within the last 30 years a time that has been marked by rapid and revolutionary advances in printing technology and both still photography and moving-picture technology and a time that has brought the advent of mass- market paperbacks, videotapes, and Super 8 films that the technological means have been developed to produce and distribute pornography on a large scale, and to do so cheaply. Combine this fact with the series of obscenity decisions handed down by the Supreme Court between 1957 and 1974 decisions which loosened and finally, in effect, removed all federal prohibition against pornography and what emerges is a seemingly airtight explanation of why pornography has become such a big business in the U.S. today. I say seemingly airtight because there's one flaw in this explanation: The fact that we now have the technological means to produce pornography in large supply does not explain why there is such a demand for it, and the fact that the Supreme Court has created a legal climate that allows pornography does not explain why so many people want pornography. So the fundamental question remains: Why is it that so many millions of us are into porn? Does pornography fulfill some need?

Perhaps the most common answer to this question is the response-to-repression theory. Long backed by liberal intellectuals, this theory argues that pornography indeed fulfills a need, and it is the need for personal and political freedom in its most exalted form. Pornography, according to this view, is literature that celebrates individual liberty: It arises, as it did so markedly during the Victorian era, as a direct and courageous challenge to restrictive sexual and political standards and those who have the power to impose them. According to this theory, Donatien Alphonse Francois de Sade, the 18th- century French pornographer whose horror-filled life and works gave us the word "sadism," was nothing less than a revolutionary hero or, in the words of Albert Camus, "the first theoretician of absolute rebellion."

Over the years, Sade and porn-as- freedom have been supported by a large number of intellectuals. Today, however, the number of intellectuals willing to go to bat for the response-to-repression theory is dwindling. One of the main arguments against the theory is that American society at present is far from repressed. Nudity and explicitness no longer shock, extramarital sexual activity is commonplace, cohabitation is called just that rather than "living in sin," the average age of first coitus has dropped to below 16 ... the list could go on. Indeed, some, among them the late Margaret Mead, have argued that American society might be better off if people, especially men, repressed their urges a little bit more. It is a fact, after all, that the United States is the most violent of all industrialized nations, and that much of the violence is sexual. Little girls and women know this full well: According to the F.B.I., one quarter of all female children in the U.S. today will be sexually molested by the age of 18, and one out of three women will be raped at least once in her lifetime.

IF you go to Baker Library and look up Women in the card catalogue, you will be directed to "see also: Family/girls, Mothers/prostitutes, Widows/young women." By contrast, if you look up Men you will be directed to "see also: Brotherhoods, Man, Masculinity, Young Men." And if you do as directed and look up Man, you will then be directed to see a wide variety of topics, including anthropology and, yes, even persons. But nowhere under either Men or Man will you see any reference to family, boys, or widowers. And nowhere will you find any reference to fathers/pimps.

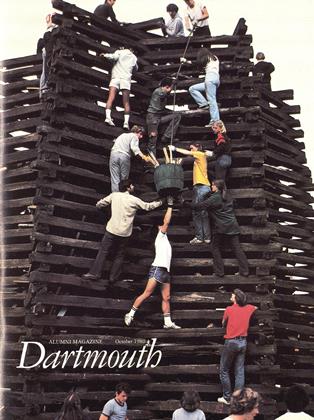

I mention this point because it il- luminates another theory currently being used to explain why pornography has grown so popular and violent in this country during the past ten years. Deriving from the Greek pornographos, meaning "writing about prostitutes," pornography originally was tied to, and reinforced, one of Western culture's deepest, most pervasive and long-standing myths, the myth that there are two kinds of women: madonnas and whores. Today, however, feminists argue that pornography is perpetrating a new myth, the myth that there is only one type of woman, and regardless of her age, intelligence, identity, and occupation, she is essentially a whore. Current porn titles like The Nuns' Secret Sex Diary,Secretaries for Reaming, WillingWaitresses, and Abuse of Schoolgirls are cited in support of this argument, as is "Women of the Ivy League Revealed," a 1979 Playboy spread for which three Dartmouth women posed.

The feminist theory of pornography, as it's been developed so far, boils down to one of backlash. Pornography, many feminists believe, has grown more popular and violent in the past ten years as a direct response to the concurrent growth of the women's movement. As women get more "uppity," men get more threatened and fearful, and pornography, many feminists believe, is a way of keeping women down, if not in fact at least in fantasy. According to the feminist analysis, pornography is an expression of the political ideology that says women are to be subordinate to men, and the reason it flourished in the Vic torian era was not so much that that age was repressed as that it was a time when feminism was widespread.

As a feminist myself, I like the feminist backlash theory; it seems to stack up so tidily, and imaging all those pornographers sitting around plotting against the women's movement makes me feel part of something very important. As one who has thought long and hard about pornography, however, I have to admit that the feminist backlash theory seems flawed. To be sure, there is probably some connection between pornography's growing popularity among men and women's attempt to upgrade their status in this society. But to say the pornography boom is a conscious response to the women's movement seems as absurdly simplistic as saying the women's movement is the result of the pornography boom. It is also, I think, to overestimate the power of the women's movement, and the intelligence, political consciousness, and conspiratorial motives of porno graphers and their customers.

Nonetheless, I think there's something to a feminist interpretation of pornography, for it refuses to ignore the misogyny in so much of today's pornography and thus points to a crucial and sadly curious fact: Ours is a culture in which expressions of hatred toward women are tolerated as expressions of hatred toward no other group would be. If you doubt this fact, ask yourself what the reaction would be if tomorrow the thousands of peep shows spread across this country featured not films of women being beaten and raped but films of Jews being clubbed and gassed. Would it seem so funny if, instead of month after month of Little Annie Fannie being mauled by would-be molesters, Playboy gave us cartoons of Little Black Sambo being hounded by lynch mobs?

PORNOGRAPHIC novels, D. H. Lawrence observed 50 years ago, "are either so ugly they make you ill, or so fatuous you can't imagine anybody but a cretin or a moron reading them, or writing them." I've selected this quote because it sums up my own reaction to many porn novels as well as the movies and photographs I've seen, and also because I think it sheds light on the real reason pornography has become so popular in this country. The point is, a lot of today's pornography is not just violent and hateful, it's also incredibly repetitious, unimaginative, and just plain stupid, moronic even. And herein, I think, lies the clue to why pornography is such a big and growing business in the U.S. today.

It is no coincidence, I think, that the 1970s were marked by a proliferation of both 400 porn magazines and mindless publications like People and Self. Pornography, it seems to me, ties in perfectly with the political apathy, the obsessive and voyeuristic concern with celebrity, the widespread hedonism, the frenzied search for status, and all the other characteristic trends of the "Me Decade." For in order to flourish as it has flourished in the past ten years pornography requires not simply a sophisticated technology and a relaxed legal atmosphere but, more fundamentally, a large-scale suspension of any sense of social responsibility. The function of pornography is not to liberate our sexuality, but to liberate us and our wallets from the habits of frugality and, more important, the habits of thought that might make us stop and question before we blow another few bucks in pursuit of our every onanistic whim. The message of today's pornography is, Whatever turns you on is okay; don't worry that what turns you on might be injurious to either you or anyone else; don't think about anything beyond your own personal gratification at this particular moment . . . don't think at all, just spend.

To question the current pornography boom is not to advocate censorship. Nor is it to imply that pornographers invented, or are primarily responsible for, the contemptuous attitudes toward women that long have pervaded Western culture. To question the pornography boom is simply to suggest that a society which spends more money on pornography, much of it hateful and moronic, than it does on conventional movies and music combined is a society that could benefit from a little self- examination.

If we can learn anything illuminating from this country's nearly 20,000 porn shops, it's not that there is animosity between men and women in this culture, it's just how mindlessly accepting we, in our relentless search for thrills, have become of this fact accepting to the point where many (some women included) do not find the animosity deeply disturbing but titillating. If magazines like Abuse andWhipping and movies like Snuff tell us anything, I think they tell us that we love to hate and hate to question just why it is we hate and whether there might not be something dangerous, even wrong, in indulging our hate. In the space of 200 years, we seem to have come full circle, from the Puritan ethic which took seriously the notion of good and evil to the Pleasure ethic which scoffs at the notion that anything that makes you feel good could possibly be evil. In the process we seem to have forgotten that not all evils exist solely in the eye of the beholder, and certain actions are still reprehensible even when whole societies accept them, find them pleasurable, and call them good.

Mary Ellen Donovan '76 is currentlywriting a book about American womenand self-esteem. Her article "The Lady andthe Truckers" appeared in the October1978 issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleAn Heir to Ledyard's Wanderlust

October 1980 By Peter Gambaccini '72

Mary Ellen Donovan

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

MARCH 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

OCTOBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

DECEMBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryArms Limitations in Webster's Time

June 1989 -

Feature

FeatureLOST IN THE TREASURE ROOM

OCTOBER 1998 By Brock Brower '53 -

Feature

FeatureChallenge

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Colleen Sullivan Bartlett '79 -

Feature

FeatureHow Public Is Music?

February 1960 By JAMES A. SYKES -

Feature

FeatureAn All-Time Dartmouth Team

October 1955 By LAURENCE H. BANKART '10 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the FALL

JANUARY 1998 By Regina Barreca '79