ANCIENT shipwrecks and sunken treasures of the Spanish Main. Shades of Blackbeard and sea chests spilling over with precious gems and pieces of eight. Historical archeology evokes quite another image: meticulous scientists searching and sifting, cataloguing artifacts for the light they may shed on civilizations of the past.

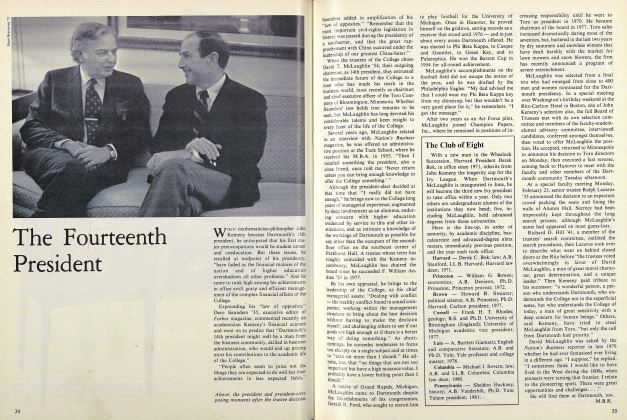

But the twain do meet in the person of R. DUNCAN MATHEWSON '6O, a consultant to the men and women who go down in the sea to ships in search of treasure. A diver as bedazzled as the next by the sight of a scatter of doubloons glittering on the ocean floor, Mathewson respects their curatorial value as much as their commercial worth. Though the treasure hunter and the historic shipwreck archeologist seem antithetical in purpose as well as style, Mathewson is convinced that they can coexist in peace, to their mutual benefit.

Among his clients is Treasure Salvors Inc., an enterprise headed by Melvin Fisher who has for almost a decade been seeking the "mother lode" of the Nuestra Sehora de Atocha, a 600-ton galleon that sank in a hurricane off the Florida Keys in 1622. Among the 260 lost were a vice admiral of the Spanish fleet, the King's Exalted Visitor to Peru, the Corregidor of Cuzco, and an assortment of merchants returning from the colonies to the mother country. In Atochas hold, according to the ship's manifest preserved in Madrid archives, was a fabulous fortune in gold and silver - the Crown's share from Bolivian mines, tax revenues on slaves sold at Cartagena, fees for papal indulgences, and 20,000 pesos for the heirs of Christopher Columbus.

The Spaniards attempted' salvage- of Atocha's store in years following, finding her, records say, still intact in 55 feet of water. But before the main treasure was recovered, another hurricane in 1628 dispersed the wreck, leaving the mother lode somewhere between Marquesas Key and the Dry Tortugas. Atocha has yielded to modern hunters - at awesome cost in money and lives - several millions in coins and ingots, golden artifacts, navigational instruments, nine cannon, and an anchor, but the bulk of the treasure - possibly $100 million worth - remains elusive.

Mathewson has been on the project since 1973, shortly after a spectacular find of some 6,000 coins in an area promptly dubbed "the Bank of Spain." Since then, one of his major jobs has been to establish archeological control so that the site could be mapped and hypotheses developed about where the major part of the ship lay.

Mathewson's working hypothesis is that Atocha, after resting intact in the deep watery grave described in 17th-century accounts, lost her sterncastle and upper decks in the second hurricane. Contrary to previous assumptions, he theorizes that the superstructure was wrenched off by the storm and swept in a northwesterly direction, the starboard upper-deck cannon were lost in one roll, the port in the next opposite, and the lightened sterncastle carried on to settle on sandy shoals called the Quicksands." After the cannon were discovered in 1975, he says, "I bet them a case, of gin that the 'mother lode would eventually be found still at the point of primary impact, that the Quicksands site represents secondary scatter."

"It's like a detective story," Mathewson says, accumulating the evidence - in this case, the kinds of artifacts and their configuration - weighing the data in light of historical, archeological, geologic, and meteorological information, and deducing the chain of events of three and a half centuries ago. To support his theory that finds to date are from secondary dispersal, Mathewson notes the nature of the artifacts found in shallow water - light armaments, the astrolabe and other navigation aids normally found on a sterncastle.

The bulk of the ship and its treasure will be found, he contends, through systematic use of the sophisticated tools of shipwreck exploration: grid-mapping search areas, scanning with magnetometers to locate iron deposits beneath bottom mud, clearing away sand and soil from likely spots with "mailboxes" - tubular devices that deflect the search boats' prop wash downward - and remote sensing from the air. "People wonder," he says, "why, with our hypothetical model on hand, we can't go straight to the major part of the wreck. But it's still a small target in an awful lot of water."

Not without reason treasure hunters and archeologists have regarded one another as adversaries. In their rush for booty, salvors have scattered and destroyed artifacts of immense cultural interest, and governmental bodies have seen no need to cooperate with commercial interests, beyond licensing their operations and taking a cut of the catch. But Mathewson has a firm conviction that each has much to contribute to the other. Salvors gamble huge sums, for the most part unavailable to public agencies or educational institutions, in their search for treasure; concomitantly, they depend on the specialized knowledge of the historian and the archeologist, without which they might be casting about hit-or-miss in the murky depths. The Atocha project makes a good case in point. It was Eugene Lyons, a historian friend of Fisher's, who found the clue in Spanish archives that shifted the search for Atocha and her sister ships 100 miles from its original location to the area between Key West and the Dry Tortugas. And it was Lyons who persuaded Mathewson, then working on historic sites in Jamaica after a stint as a government archeologist in Ghana, to sign on as a consultant to Fisher. And now Mathewson has developed the most plausible hypothesis about where Atocha's hull lies.

Atocha has proved a landmark case in several ways, Mathewson points out. Fisher's search has been beset from the start by financial problems, legal entanglements, and human tragedy. Shortly after his son Dirk found the cannon, the young man and his wife were drowned. Conflicting claims by Floridian and federal agencies have prompted litigation all the way to the Supreme Court, and the salvors' share of the treasure found to date has been released only recently. One benefit of the legal morass may be the passage of a law, now before the Congress, which will spell out the rights and obligations of all parties and provide protection for non-renewable cultural resources while safeguarding the entrepreneur's interests.

This month, Mathewson is convener of a conference on Florida Historic Wreck Archeology, funded in part by the Endowment for the Humanities and co-sponsored by Florida Atlantic University, where he is completing a doctoral program. He hopes that bringing together commercial salvors, government archeologists, historians, anthropologists, representatives of the Smithsonian Institution and independent research groups, to discuss their distinct and mutual interests, will help establish common ground for the common good. After he finishes his dissertation on shipwreck archeology, he plans to write a popular book on the subject to alert the public, already concerned with the depletion of natural resources, to the need for preserving cultural resources as well - "as non-renewable as public lands or oil reserves."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

November | December 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Feature

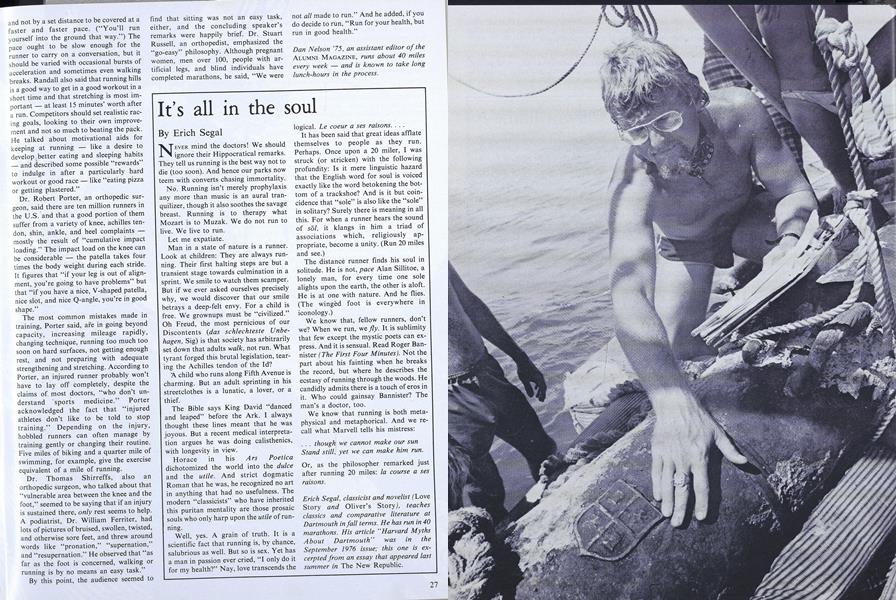

FeatureSee How They Run

November | December 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

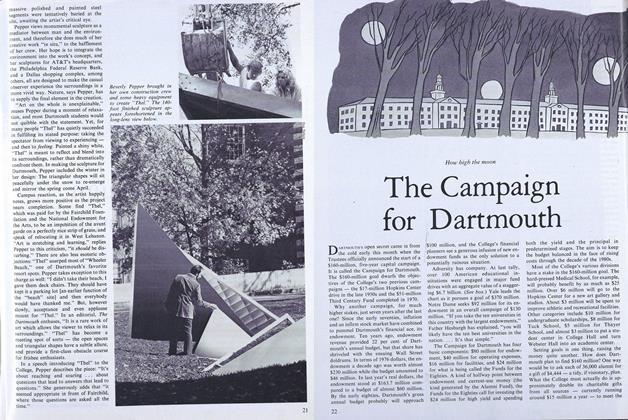

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

November | December 1977 -

Article

ArticleThe DCMB Double-entendre March

November | December 1977 By Anne Bagamery -

Article

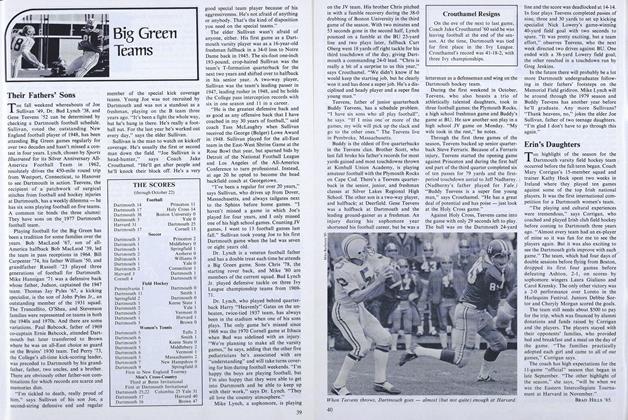

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

November | December 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleTheir Fathers' Sons

November | December 1977