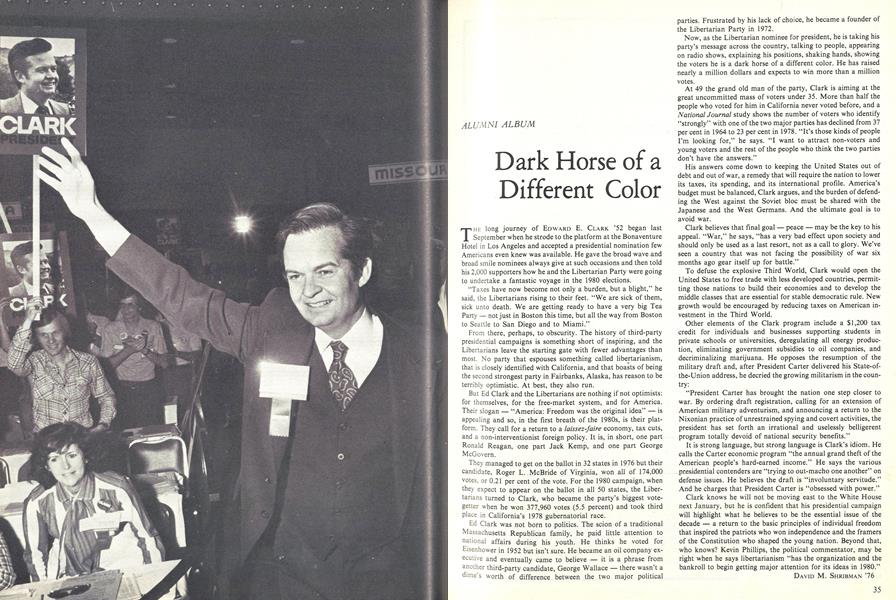

The long journey of Edward E. Clark '52 began last September when he strode to the platform at the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles and accepted a presidential nomination few Americans even knew was available. He gave the broad wave and broad smile nominees always give at such occasions and then told his 2,000 supporters how he and the Libertarian Party were going to undertake a fantastic voyage in the 1980 elections.

"Taxes have now become not only a burden, but a blight," he said, the Libertarians rising to their feet. "We are sick of them, sick unto death. We are getting ready to have a very big Tea Party-not just in Boston this time, but all the way from Boston to Seattle to San Diego and to Miami."

From there, perhaps, to obscurity. The history of third-party presidential campaigns is something short of inspiring, and the Libertarians leave the starting gate with fewer advantages than most. No party that espouses something called libeitarianism, that is closely identified with California, and that boasts of being the second strongest party in Fairbanks, Alaska, has reason to be terribly optimistic. At best, they also run.

But Ed Clark and the Libertarians are nothing if not optimists: for themselves, for the free-market system, and for America. Their slogan-"America: Freedom was the original idea"-is appealing and so, in the first breath of the 1980s, is their platform. They call for a return to a laissez-faire economy, tax cuts, and a non-interventionist foreign policy. It is, in short, one part Ronald Reagan, one part Jack Kemp, and one part George McGovern.

They managed to get on the ballot in 32 states in 1976 but their candidate, Roger L. McBride of Virginia, won all of 174,000 votes, or 0.21 per cent of the vote. For the 1980 campaign, when they expect to appear on the ballot in all 50 states, the Libertarians turned to Clark, who became the party's biggest votegetter when he won 377,960 votes (5.5 percent) and took third place in California's 1978 gubernatorial race.

Ed Clark was not born to politics. The scion of a traditional Massachusetts Republican family, he paid little attention to national affairs during his youth. He thinks he voted for Eisenhower in 1952 but isn't sure. He became an oil company executive and eventually came to believe it is a phrase from another third-party candidate, George Wallace-there wasn't a dime's worth of difference between the two major political parties. Frustrated by his lack of choice, he became a founder of the Libertarian Party in 1972.

Now, as the Libertarian nominee for president, he is taking his party's message across the country, talking to people, appearing on radio shows, explaining his positions, shaking hands, showing the voters he is a dark horse of a different color. He has raised nearly a million dollars and expects to win more than a million votes.

At 49 the grand old man of the party, Clark is aiming at the great uncommitted mass of voters under 35. More than half the people who voted for him in California never voted before, and a National Journal study shows the number of voters who identify "strongly" with one of the two major parties has declined from 37 per cent in 1964 to 23 per cent in 1978. "It's those kinds of people I'm looking for," he says. "I want to attract non-voters and young voters and the rest of the people who think the two parties don't have the answers."

His answers come down to keeping the United States out of debt and out of war, a remedy that will require the nation to lower its taxes, its spending, and its international profile. America's budget must be balanced, Clark argues, and the burden of defending the West against the Soviet bloc must be shared with the Japanese and the West Germans. And the ultimate goal is to avoid war.

Clark believes that final goal-peace-may be the key to his appeal. "War," he says, "has a very bad effect upon society and should only be used as a last resort, not as a call to glory. We've seen a country that was not facing the possibility of war six months ago gear itself up for battle."

To defuse the explosive Third World, Clark would open the United States to free trade with less developed countries, permitting those nations to build their economies and to develop the middle classes that are essential for stable democratic rule. New growth would be encouraged by reducing taxes on American investment in the Third World.

Other elements of the Clark program include a $1,200 tax credit for individuals and businesses supporting students in private schools or universities, deregulating all energy production, eliminating government subsidies to oil companies, and decriminalizing marijuana. He opposes the resumption of the military draft and, after President Carter delivered his State-of- the-Union address, he decried the growing militarism in the country:

"President Carter has brought the nation one step closer to war. By ordering draft registration, calling for an extension of American military adventurism, and announcing a return to the Nixonian practice of unrestrained spying and covert activities, the president has set forth an irrational and uselessly belligerent program totally devoid of national security benefits."

It is strong language, but strong language is Clark's idiom. He calls the Carter economic program "the annual grand theft of the American people's hard-earned income." He says the various presidential contenders are "trying to out-macho one another" on defense issues. He believes the draft is "involuntary servitude." And he charges that President Carter is "obsessed with power."

Clark knows he will not be moving east to the White House next January, but he is confident that his presidential campaign will highlight what he believes to be the essential issue of the decade-a return to the basic principles of individual freedom that inspired the patriots who won independence and the framers of the Constitution who shaped the young nation. Beyond that, who knows? Kevin Phillips, the political commentator, may be right when he says libertarianism "has the organization and the bankroll to begin getting major attention for its ideas in 1980."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMaking Books

April 1980 By Robert H. Ross -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWho in Hell Was Jeff Tesreau?

April 1980 By Edward D. Gruen '31 -

Article

ArticleAdapting to the Heights

April 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1980 By DAVID R. BOLDT

David M. Shribman '76

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1983 -

Article

ArticleA Certain Uncertainty

September 1975 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleThe Silly Season

November 1975 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleA Son's Reflections

January 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

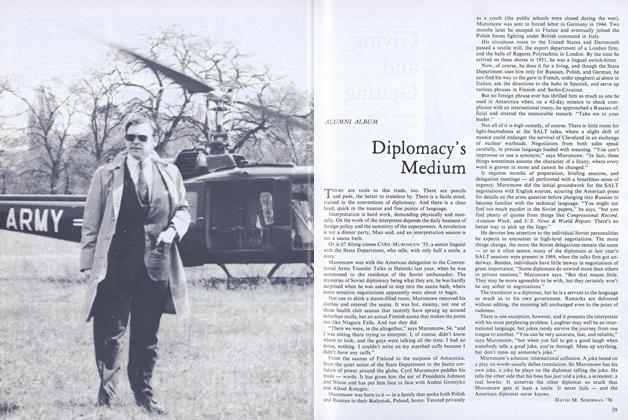

ArticleDiplomacy's Medium

December 1979 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

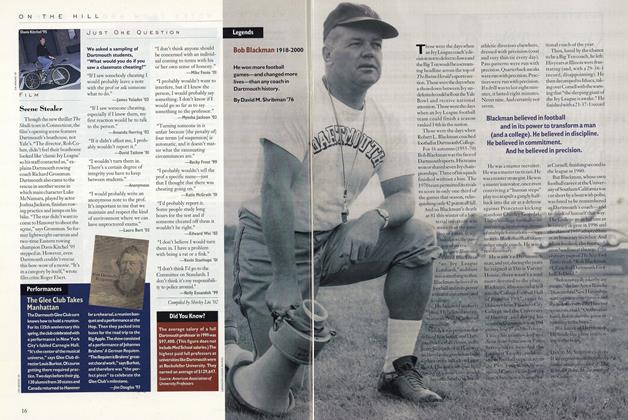

ArticleLegends

JUNE 2000 By David M. Shribman '76

Article

-

Article

ArticleCLOSE 1926 ADMISSION LISTS ON APRIL FIRST

December 1921 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH NIGHT SET FOR NOVEMBER 11

NOVEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleProfessor Eddy Elected President of Hobart

February 1936 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

DECEMBER 1969 -

Article

ArticleDoctors' Dilemma

OCTOBER 1982 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

Sept/Oct 2006 By BONNIE BARBER