THERE are tools to this trade, too. There are pencils and pads, the better to translate by. There is a facile mind, trained in the conventions of diplomacy. And there is a clear head, quick in the nuance and fine points of language. Interpretation is hard work, demanding physically and mentally. On the work of the interpreter depends the daily business of foreign policy and the summitry of the superpowers. A revolution is not a dinner party, Mao said, and an interpretation session is not a sauna bath.

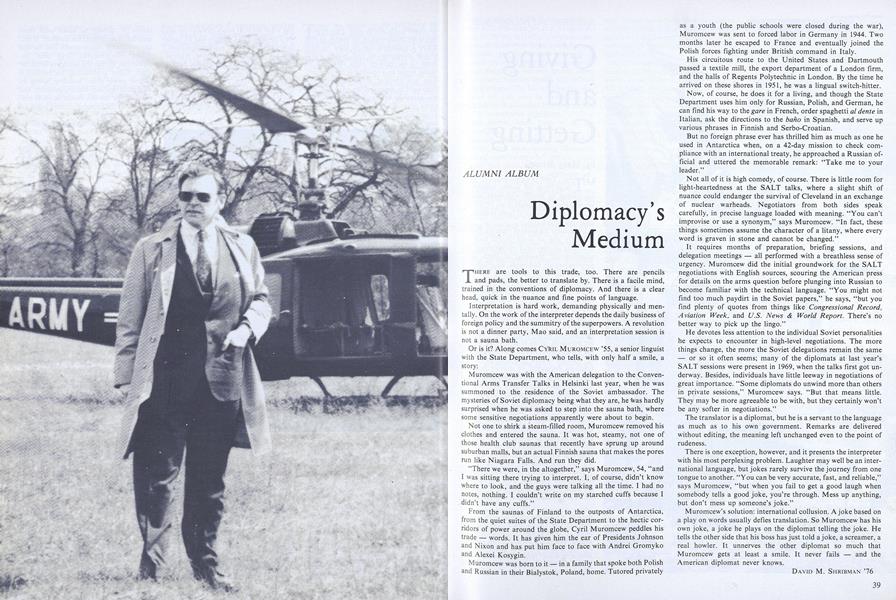

Or is it? Along comes CYRIL MUROMCEW '55, a senior linguist with the State Department, who tells, with only half a smile, a story:

Muromcew was with the American delegation to the Conventional Arms Transfer Talks in Helsinki last year, when he was summoned to the residence of the Soviet ambassador. The mysteries of Soviet diplomacy being what they are, he was hardly surprised when he was asked to step into the sauna bath, where some sensitive negotiations apparently were about to begin.

Not one to shirk a steam-filled room, Muromcew removed his clothes and entered the sauna. It was hot, steamy, not one of those health club saunas that recently have sprung up around suburban malls, but an actual Finnish sauna that makes the pores run like Niagara Falls. And run they did.

"There we were, in the altogether," says Muromcew, 54, "and I was sitting there trying to interpret. I, of course, didn't know where to look, and the guys were talking all the time. I had no notes, nothing. I couldn't write on my starched cuffs because I didn't have any cuffs."

From the saunas of Finland to the outposts of Antarctica, from the quiet suites of the State Department to the hectic corridors of power around the globe, Cyril Muromcew peddles his trade - words. It has given him the ear of Presidents Johnson and Nixon and has put him face to face with Andrei Gromyko and Alexei Kosygin.

Muromcew was born to it - in a family that spoke both Polish and Russian in their Bialystok, Poland, home. Tutored privately as a youth (the public schools were closed during the war), Muromcew was sent to forced labor in Germany in 1944. Two months later he escaped to France and eventually joined the Polish forces fighting under British command in Italy.

His circuitous route to the United States and Dartmouth passed a textile mill, the export department of a London firm, and the halls of Regents Polytechnic in London. By the time he arrived on these shores in 1951, he was a lingual switch-hitter.

Now, of course, he does it for a living, and though the State Department uses him only for Russian, Polish, and German, he can find his way to the gare in French, order spaghetti al dente in Italian, ask the directions to the baño in Spanish, and serve up various phrases in Finnish and Serbo-Croatian.

But no foreign phrase ever has thrilled him as much as one he used in Antarctica when, on a 42-day mission to check compliance with an international treaty, he approached a Russian official and uttered the memorable remark: "Take me to your leader."

Not all of it is high comedy, of course. There is little room for light-heartedness at the SALT talks, where a slight shift of nuance could endanger the survival of Cleveland in an exchange of nuclear warheads. Negotiators from both sides speak carefully, in precise language loaded with meaning. "You can't improvise or use a synonym," says Muromcew. "In fact, these things sometimes assume the character of a litany, where every word is graven in stone and cannot be changed."

It requires months of preparation, briefing sessions, and delegation meetings - all performed with a breathless sense of urgency. Muromcew did the initial groundwork for the SALT negotiations with English sources, scouring the American press for details on the arms question before plunging into Russian to become familiar with the technical language. "You might not find too much paydirt in the Soviet papers," he says, "but you find plenty of quotes from things like Congressional Record,Aviation Week, and U.S. News & World Report. There's no better way to pick up the lingo."

He devotes less attention to the individual Soviet personalities he expects to encounter in high-level negotiations. The more things change, the more the Soviet delegations remain the same - or so it often seems; many of the diplomats at last year's SALT sessions were present in 1969, when the talks first got underway. Besides, individuals have little leeway in negotiations of great importance. "Some diplomats do unwind more than others in private sessions," Muromcew says. "But that means little. They may be more agreeable to be with, but they certainly won't be any softer in negotiations."

The translator is a diplomat, but he is a servant to the language as much as to his own government. Remarks are delivered without editing, the meaning left unchanged even to the point of rudeness.

There is one exception, however, and it presents the interpreter with his most perplexing problem. Laughter may well be an international language, but jokes rarely survive the journey from one tongue to another. "You can be very accurate, fast, and reliable," says Muromcew, "but when you fail to get a good laugh when somebody tells a good joke, you're through. Mess up anything, but don't mess up someone's joke."

Muromcew's solution: international collusion. A joke based on a play on words usually defies translation. So Muromcew has his own joke, a joke he plays on the diplomat telling the joke. He tells the other side that his boss has just told a joke, a screamer, a real howler. It unnerves the other diplomat so much that Muromcew gets at least a smile. It never fails - and the American diplomat never knows.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

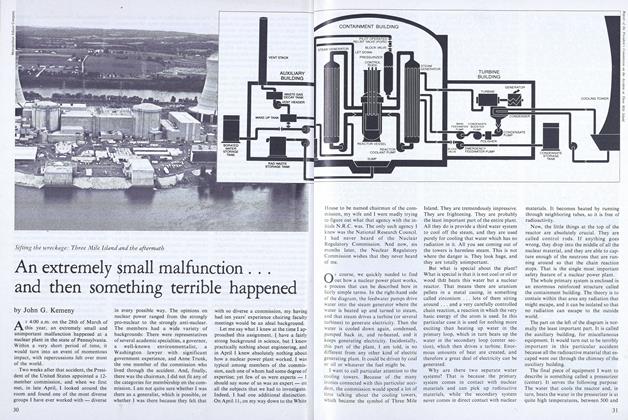

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R. -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80

DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76

-

Article

ArticleA Certain Uncertainty

September 1975 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Books

BooksSoiled Pinstripes

October 1979 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

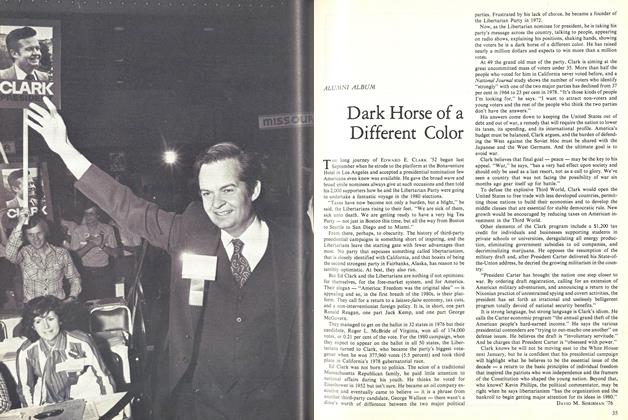

ArticleDark Horse of a Different Color

April 1980 By David M. Shribman '76 -

Books

BooksDisorderly Houses

October 1980 By David M. Shribman '76 -

Books

BooksBecoming Yankees

SEPTEMBER 1981 By David M. Shribman '76

Article

-

Article

ArticleSECRETARIES HAVING 100%RECORD FOR THE YEAR MAGAZINEL CLASS NOTES

June 1933 -

Article

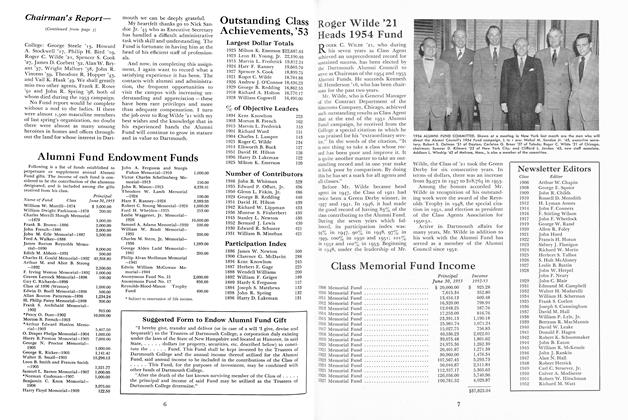

ArticleOutstanding Class Achievements, '53

December 1953 -

Article

ArticleHealthy App-etite

MAY | JUNE By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticleLACROSSE

July 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

ArticleDifferent at Dartmouth

APRIL 1998 By Michelle Gregg '99 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

January 1950 By Parker Merrow '25