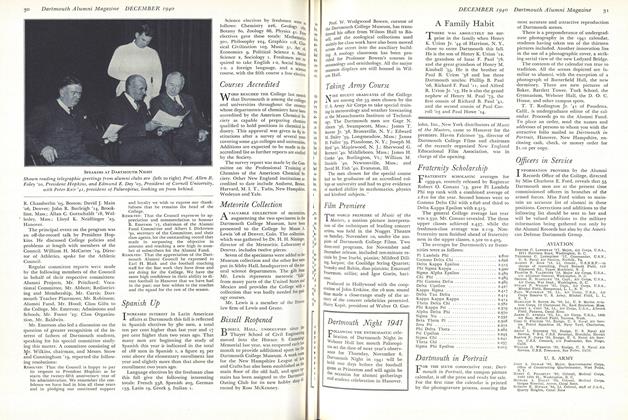

Ever since the DNA code was broken science and industry have continued to probe the frontiers of genetic engineering. At the same time, people inside and outside the field have been asking questions about the ethics involved in tampering with nature. It's not unusual for Dr. Frankenstein's monster to be mentioned. Michael Ross '71—a vice president of medicinal and biomolecular chemistry at Genentech, Inc.—is one insider who's glad the questions are being asked.

During the winter term Ross was in Hanover for a series of meetings with members of the Medical School faculty, Thayer, and the College's molecular genetics and chemistry departments. He also found time for a public discussion about the ethics of genetic engineering, and he added considerable expertise to the equation. For his San Francisco-based company is the flagship and pioneer in the genetic engineering of health care products—including Activase, a new drug that dissolves blood clots and is used in the emergency treatment of heart attacks; genetically engineered human insulin; and a potential anti-cancer drug, alpha interferon.

Michael Ross's Dartmouth degree was in chemistry, Phi Beta Kappa, and his Ph.D. is from the California Institute of Technology. He returns to Hanover periodically, where his father, Robert M. Ross, is Adjunct Professor of Chemistry.

The lecture on ethics employed numerous examples and explanations too technical and detailed for this brief report. But his position is clear. "It's something that raises lots of emotions—ethics always does—and it ought to . . . There are no answers to ethics. Yes and no is something you rarely come by . . . We've had a lot of discussions at the company about ethics, what we should work on and what we shouldn't work on. [But] companies don't have ethics. Individual people have ethics . . . [While] I don't think the kind of science we do has any more ethical problems than the science anybody else does, people think about the ethics of what we do moreand I actually like that."

Ross described the close parallels between genetic science and "classical" natural science, which ordinarily is thought "ethically bland." He also emphasized that nature does its own genetic engineering, without any help from the lab. "Quite often bacterial cells interchange DNA by mating."

He believes that the risks in this new field "are identical to other kinds of science/' such as the selective breeding of animals or the hybridization of plants. When a scientist is dealing with disease-causing bacteria, "normal scientific standards" must apply, whether one is a classical scientist or a gene engineer. Further, Ross endorses the work of, and the guidelines proposed by, the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Behaviorial Research—a group of 28 bio-medical specialists he called unusually effective. Michael Ross's conclusion and advice on the ethics of genetic engineering: keep up the discussion.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJonathan Corncob and Other Almost Classics

May 1988 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureRunning with the Big Boys

May 1988 By Mike Fadil '85 -

Feature

FeatureAt Dartmouth, the Intellectual Is on the Margin

May 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Feature

FeatureDear President Freedman...

May 1988 By Tom Bloomer '53 -

Article

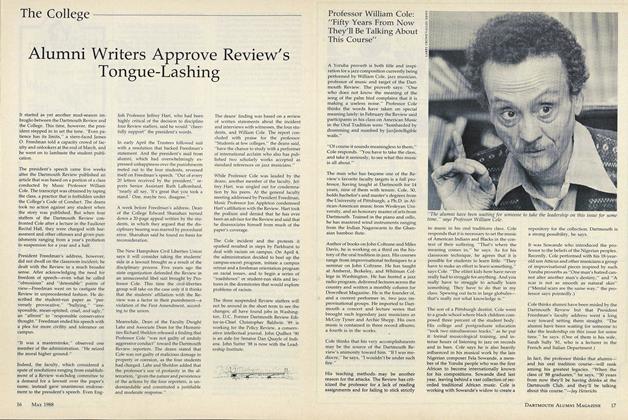

ArticleAlumni Writers Approve Review's Tongue-Lashing

May 1988 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorResponse: The Real Women's Issues

May 1988 By Mary G. Turco