THE INVISIBLE WAR: Pursuing Self-Interests at Work by Samuel Culbert and John McDonough '59 Wiley, 1980. 226 pp. $14.95

Specialized books by social scientists cannot often aspire to the best-seller lists. But this one might just make it, if for no other reason than the near-universal relevance of its subject matter. For "this is a book," the authors write, "about modern organizations and the covert battles that take place as people pursue their self-interests in the name of organizational effectiveness." Ask not for whom Culbert and McDonough's bell so direly tolls; it tolls, alas, for most of us. It is the organization man's vademecum, all tightly compacted into 226 pages and written by two behavioral scientists, specialists in organizations, who teach at the UCLA Graduate School of Management.

Culbert and McDonough are realists. Not for them the high-minded principle of the medieval monk: laborare est orare, work is prayer. Rather the pragmatic maxim of the modern organization man: laborare est bellare, work is warfare. Total, unremitting, lethal warfare in which we the combatants are, as usual, the chief casualties. "Each day," the authors begin, "we march off to an invisible war. We fight battles we don't know we're in, we seldom understand what we're fighting for, and worst of all, some of our best friends turn out to be the enemy. Our average workday consists of going to the office, sitting in meetings, speaking on the telephone just talking to people. Yet we limp home physically battered and mentally anguished. It's like being attacked by a neutron bomb the buildings are intact but the people are decimated."

For our grievous, battered state the authors offer no "packaged solutions and instant cures." Nor did their research into the previous literature on organizations afford much enlightenment; the three most commonly suggested solutions therein (based on the rational, the humanistic, and the personal- power theories) they found to be either excessively naive or excessively cynical about human behavior within organizations. What is needed, then and what they offer in this book is an entirely new "perspective" the word is their own which on the one hand realistically acknowledges "the inevitable fact that people are always looking for ways to pursue their self-interests" but at the same time shows "well-intentioned people how self- interests can be pursued without brutality, while contributing to the organization's cause."

Though Culbert and McDonough deal with the effects of internecine organizational warfare, their major concern is to analyze its causes. Their interest is in treating the disease itself, not its symptoms. Their prescription is therefore radical; it requires not merely that we act differently but think differently. "What we have to propose," they conclude, "is much more than just another openness theory. It's a way of thinking and operating that makes the personal components in one's participation more visible and makes individual variances from the organization's mission more apparent and available for discussion."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Animal and The Hypermasculine Myth

September 1980 By Leonard L. Glass -

Feature

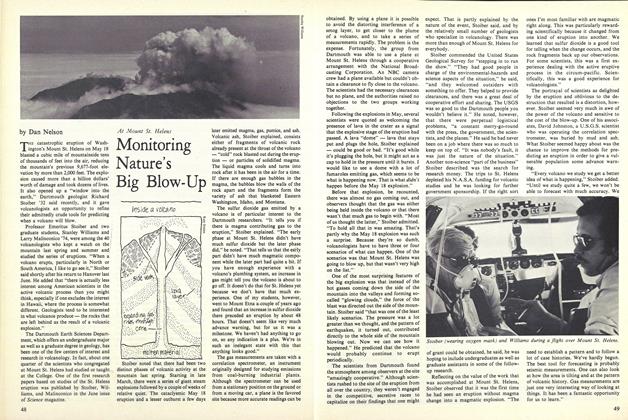

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

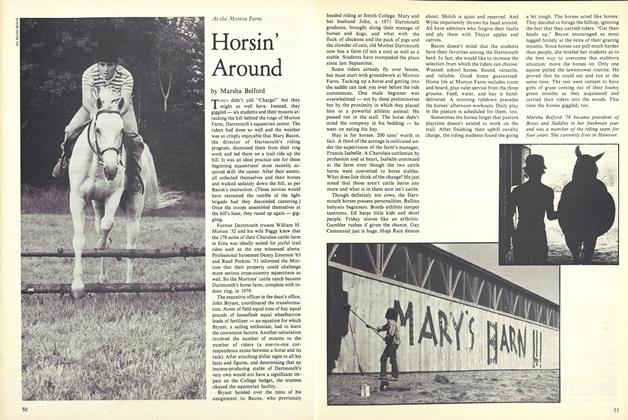

Cover StoryHorsin' Around

September 1980 By Marsha Belford -

Article

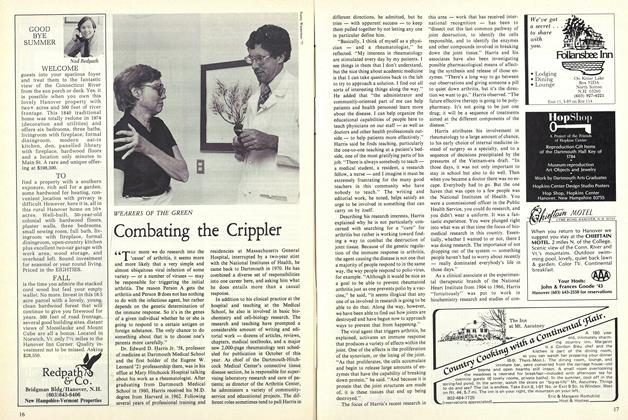

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleColor, Charm, Whatever

September 1980 -

Article

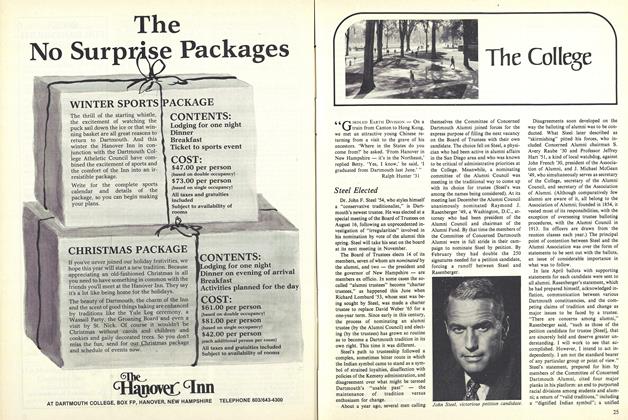

ArticleSteel Elected

September 1980

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on an expatriate's look homeward and on a bookman in a vast, sparsely inhabited region

October 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksCity Views

April 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksObserving Life

JAN./FEB. 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

MARCH 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksOut of the Night

November 1978 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November 1917 -

Books

BooksGAUSERIES—LA VIE SCOLAIRE,

November 1949 By Charles R. Bagley -

Books

BooksTHE NEW CROSS-COUNTRY SKI BOOK.

JANUARY 1972 By DAVID BRADLEY '38, M. D. -

Books

BooksOLD QUOTES AT HOME.

JANUARY 1968 By MAUDE FRENCH -

Books

BooksSubways Run on Time

May 1975 By MORTON M. KONDRACKE '60 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN SHIPS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By STEPHEN G. NICHOLS JR. '58

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on an expatriate's look homeward and on a bookman in a vast, sparsely inhabited region

October 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksCity Views

April 1977 By R.H.R.