A bicycle on the ceiling,dry-land birling and other products of the inventive mind

A small group of business executives, engineers, and professors gathered at the Thayer School of Engineering near the end of fall term to review new product proposals for the recreational and leisuretime markets. What was unusual about this meeting was that the designs under consideration were developed by students, most of them Dartmouth sophomores, as part of their course work for ES 21 - "Introduction to Engineering." Ten years or so ago former Thayer Dean Myron Tribus and Professors Russell Stearns '37 and Robert Dean designed the course to give the beginning engineer a look at the profession, to acquaint him or, increasingly, her with its economic, social, and technical aspects, and to provide the opportunity to solve "real world" problems.

According to Carl Long, Thayer's present dean, "a different problem area is chosen each year on the basis of timeliness, potential for meaningful student effort, and social significance." This year's projects, focusing on recreational needs, included devices to crank a bicycle up to the ceiling for storage, to paddle a canoe by foot-power, and to simulate log-rolling, or birling, on dry land. Student teams also developed a ski exercise machine, a hockey helmet with improved ventilation, padding, and face protection, prescription goggles for swimmers, and a Dry Ice food cooler for boaters. There was even a replacement designed for the 35-pound weight thrown by trackmen in indoor competition; the current version, which sells for about $90, frequently breaks and spills lead shot all over the track and Astroturf.

In past years ES 21 projects have centered around such themes as solid waste disposal, urban parking needs, pollution reduction, the prevention of injuries and fatalities in highway accidents, desalination, and aids for the handicapped. One early project, for example, transformed alphanumeric typing into braille. Occasionally one of the products designed by students is patented and marketed. A garbage compactor was purchased by industry, and OSMONICS, a desalination process, is now publicly owned and last year generated $2 million in sales.

The emphasis of the course has been on design, but traditionally the Tuck School faculty has been involved in lecturing on business administration. This year, for example, Jordan Baruch, professor at both Tuck and Thayer, directed the course. This combination "of approaches is thought to provide the student with a more realistic introduction to engineering since solutions to design problems must be economically as well as technically feasible.

AT the beginning of the term in ES 21, students are randomly divided into simulated research and development companies with about seven members, a faculty adviser, and a teaching assistant. Each company is presented with a request for design proposals from a fictitious industrial company whose president, the course director, executes contracts and reviews progress. The adviser and teaching assistants act more as coaches than teachers, asking questions and introducing students to the available research facilities.

The student companies, each with officers and a budget, decide on a specific product, make a preliminary proposal, research and test design ideas, and construct a prototype. They also carry out a cost analysis, study the potential market, formulate a marketing strategy, and develop a production timetable. Profits, of course, are also estimated in an effort to encourage potential investors. A budget of $112 covers materials and phone calls for each company. Dean Long estimates that it would take close to $20,000 for actual firms to prepare comparable proposals if the cost of labor and research were counted.

Not all the proposals submitted by students have potential, but what is remarkable, says Baruch, the course director, is that the majority of them have more potential than the average design submitted to development firms for funding. The most common fault with the student projects is their lack of refinement, but this is largely because of the limited life of each company. The term lasts only ten weeks and each student is involved in taking two other courses.

What prevents more of the good proposals from reaching the ultimate consumers - us - is lack of continuous contact with potentially interested firms and no ready funding mechanism. Students are rarely in the position to invest to the extent that would be necessary to obtain patents, advertise, and begin production. Some products, such as a system to convert cow manure into methane, have limited consumer appeal. Others, such as a computerized credit card parking meter system, would not be economically practical in use. (Credit card billing for meters would delay collection of the small fees for up to two months and involve the loss of significant interest revenue.)

Baruch says that members of the review board were so impressed with the proposals they saw this year that some of "-he student companies were approached about carrying their projects forward. The tact that the board was composed of executives from such firms as Exxon Enterprises, Gillette, AMF Sportwear, and the more local, Lebanon-based CREARE Innovations, Inc., indicates that these efforts were being evaluated with some awareness of production and marketing realities. Industry in general, according to Baruch, has been very enthusiastic about the course and cooperative in supplying students with information. One firm that supplied details about its products later offered a job to the student who sought them. Another student found a competitor "pretty suspicious when I asked about the market" - which can be taken to mean that the student and his probing were being taken seriously.

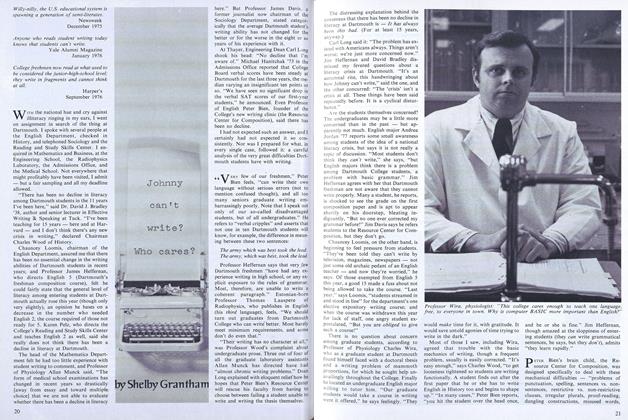

WHEN we heard that these student-in-vented recreational devices would be presented at the Thayer School, we wondered if we would see something on the order of Frisbees, Hula-Hoops, and SuperBalls. When the first product, "Project Exerski - The New Ski Exercise Innovation" was introduced it appeared we would see something more substantial, if not as marketable.

Exerski looks like a cross between a jumping jack and a clothes rack. Made of a shock absorber, swivel joints, springs, and steel tubing which support a pair of rotating foot platforms and a set of handlebars, it was, we were assured, "a machine that would work on the development of leg muscles while improving endurance and coordination." All this to help protect the average skier from injury.

The hour-long presentation explained the benefits, construction, production, and marketing details of the device. The Exerski sales staff presented a demand curve and estimated market saturation in six years. With Exerski retailing for about $250, and costing $123 to make, a $47 profit per unit was projected - based on sales of 11,000 units per year. Figuring costs of space, production, loans, advertising, and labor, Exerski stated they would only need $800,000 capital to start with. It all added up somehow to an estimated 42.1 per cent return on investment before taxes.

During the question and answer period the review board quibbled about the size of the market, patentability, safety precautions, and cost analysis. Someone asked for a demonstration. The engineer, somewhat reluctantly it seemed, climbed on and began bouncing up and down - until the upright standard pole bent at the base connection. Some modifications, it was conceded, were needed at a few crucial joints.

Rec Technics came up with "Convert-a-Rack, the newest dimension in storage and transportation of bicycles ... a reasonably priced, dual-functioning bicycle storage and transportation caddy." Designed to appeal primarily to residents of small apartments or dormitories, the device utilizes a rack that is taken off a car and hitched to a pole in a room. The owner then crawls under his bike as it rests on the stand and winches it up to the ceiling and out of the way.

The Convert-a-Rack people felt they had licked the main problems plaguing the bicycle owner - storage and theft prevention. They eliminated the problem of hanging a bicycle from the ceiling without damaging the interior of the room by utilizing a telescoping vertical pole upon which the bike hangs and which is held between the floor and ceiling by a pressure fit. Then there was the problem of the "large amount of force caused by the bicycle's weight about the point of attachment to the storage pole which creates tremendous frictional forces up and down the pole" - solved by the use of a special plastic roller assembly. Estimating the weight of two bicycles plus the frictional forces to be in the neighborhood of 120 pounds, Rec Technics discarded an "automobile jack-type elevation device" (because of the cost of machining notches in the pole) in favor of a boat-type winch assembly.

The Rec Technics report included "centric loaded beam" formulas, market surveys, material and shipping cost estimates, production schedules, breakdowns of operational costs, and estimates of proposed first-year sales of 22,500 units at a wholesale cost to dealers of $32 per unit. The review board seemed impressed and offered suggestions on 'ways to elevate the bicycle without crawling under it. One major criticism was that the bike seemed to be as much in the way hanging from the ceiling as resting on the floor.

The Dry Ice icebox people, Kool, Inc., were impressive in that their project was simple, inexpensive, and involved little capital investment. They made points with the review board when they served orange juice chilled in their cooler. The board was worried about the "protectability" of the design which could be easily copied by present Dry Ice manufacturers.

The HERO hockey helmet company designed a well-researched helmet with integrated face mask combining visibility, efficiency, comfort, and protection. Impressed by the quality of the molded prototype, the board again cautioned that the unpatentable design could easily be copied by an established manufacturer and the new company forced out of the market.

Later in the evening practical-looking prescription swim goggles were presented along with an imaginative mechanism, a "Hydropod," which supposedly satisfied "the need for a leg-powered propulsion system for canoes."

The Dead Weight proposal, a new design for the 35-pound weight used in indoor track competition, looked solid enough and received the endorsement of track coach Ken Weinbel. The project engineer was convinced of the weight's indestructibility - in addition to testing in the fieldhouse he had spent several hours the night before the presentation dropping the weight from his second-story window.

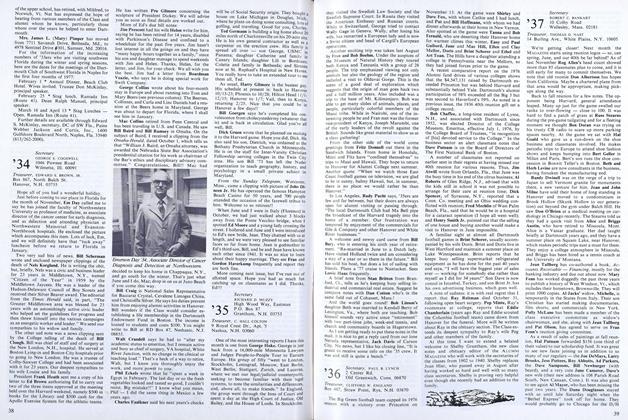

The most popular invention was the hiding machine, the dry-land log-rolling simulator. We were swayed by the sales pitch which described birling as "an exciting, active, competitive sport with an interesting history and a great potential for a sensational future." The sales manager went so far as to promote the birling system "as the most economic, compact, competitive sport in existence," and prepared charts showing the cost and space advantages of birling over such other sports as hockey, football, basketball, and lacrosse.

The company built its prototype for $34.47 worth of materials. The machine consists of an axle-mounted wooden cylinder six feet long and 14 inches in diameter. Weighing 64 pounds, but built solid enough for heavy use, it can withstand a total vertical force of 500 pounds. If the design were produced and marketed, you could probably buy one for about 5250. Purchase of a rubber mat, to protect against injury from falls, is recommended.

One feature of the machine is a provision made for tightening axle bearings in order to reduce the log's rotational speed. The team also proposed some improvements that would more closely simulate the properties of a real floating log. Adding weight or connecting a dense flywheel would "increase the cylinder's rotational inertia and the installation of springs under the axle supports would lend an effect of buoyancy.

Advertising would be aimed at schools, parks, recreation departments, and businesses. Exhibitions and contests would be organized. After presentations by the marketing staff, engineering department, technicians, and a summary by the female president of the six-person company, the review board was given a demonstration. The two birlers jumped into the air at the same time to mount the log and then turned it with their feet until one of them fell off. It didn't take long. Professional contests, we were told, might last up to 30 minutes. No one challenged the winner.

The review board, after evaluating all the proposals, votes on whether or not to fund them, based on an estimation of marketing success, the technical feasibility, quality of the report, and the level of the business analysis. No funds are actually appropriated, but the majority of this year's projects were accepted. A couple of the products, Baruch wouldn't say which ones, are seriously under consideration for further development. If someone knocks on your door with a log-rolling machine under his arm, remember, you saw it here first.

Project Exerski: a 42.1 per cent return on an $800,000 investment (somehow).

The 35-pound Dead Weight: testing went out the window.

At a cost of $34.47 in materials (right) the dry-landbirling machine could, wewere told, revolutionizecompetitive sport. Well,they laughed at the Frisbee.

Dan Nelson '75 is co-editor of class notesfor the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleThe Quirk Formula

January 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleThe Chuggers

January 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH '78 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1972

January 1977 By JOHN D. BURKE, DAVID J. FRIEND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

January 1977 By WALTER C. DODGE, THEODORE R. MINER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

January 1977 By GEORGE E. COGSWELL, EDWARD S. BROWN, JR.

DAN NELSON

-

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

JUNE 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

OCT. 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFaces from the Past

December 1976 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryKevin Ritter '98 Lloyd Lee '98, Brad Jefferson '98

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

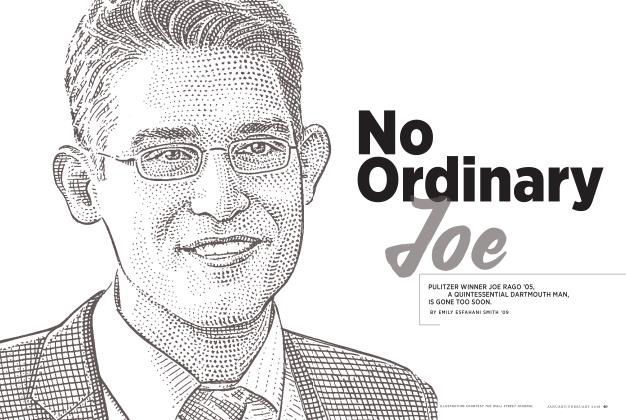

FeatureNo Ordinary Joe

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2018 By EMILY ESFAHANI SMITH ’09 -

Feature

FeatureWelcome to the dark places

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Rob Eshman -

FEATURE

FEATUREMy Writing Routine

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Lesson Tabled

MARCH 1995 By Ursula Gibson '76