In a tribute written long after his death, a writer for The Dartmouth called Joseph Anthony Dallet '27 "the first Dartmouth man killed in World War II." He died October 17, 1937, near Sargossa, Spain an officer of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade leading an attack across open ground in the face of fascist gunfire.

Last month, a dozen of Joe Dallet's old comrades-in-arms came to Hanover for what was probably the most comprehensive academic gathering ever held to assess the Spanish Civil War. The old soldiers told old war stories. Pete Seeger sang them the songs of that war. An exhibition of the poster art and the literature emerging from the conflict was mounted at Baker Library and Hopkins Center. Spanish poet Rafael Alberti, who had read his work to the soldiers of the republic in the trenches near Madrid, now in his ninth decade came to the College to read again those same poems.

Steve Nelson, Dallet's best wartime friend, came from Pittsburgh to talk about the young soldier, whom he recalled as "bent on fighting fascism." Nelson expressed the hope that one day a memorial to Dallet might be established at the College or that "maybe some student can learn something from what he did."

According to his delayed obituary, Dallet was the son of a prosperous Long Island garment manufacturer. Although he was a good athlete and a good scholar, he was generally considered a loner and a misfit during his years at Dartmouth. He sold insurance for a time after graduation, then became a union organizer in the Pennsylvania coalfields, joining the Communist Party along the way.

Dallet was intent on going to Spain, Nelson said, and the two went together, on a boat that was sunk from under them off the French coast. They were among 17 who were arrested as they made it to shore. Marching off to jail in chains, Dallet happened to spot a piano in an elegant French home. He complimented the owner, was invited to play, then impressed a hastily assembled audience that included the local magistrate with his musical talent. Adding the "Marseillaise" to Chopin in his spontaneous concert soon had Dallet and his friends out of their chains and over the Pyrenees into Spain. Ordinarily, Nelson added, Dallet avoided admitting he could play the piano or that his parents had money or that he had indulged in such elite pleasures as traveling first class in Europe or graduating from an Ivy League college.

The words in the long-delayed obituary made an appropriately flowery tribute for a victim of a much-romanticized war: "Winters are cold in the Spanish city of Sargossa, and its two ancient cathedrals point skyward like dead fingers or rusty rifles thrust in the earth and cold winds sweep the outlying barren hills that hold the dust of Joe Dallet. He sleeps in Spain beneath a soil he thought would be free. Not that it was his soil America had no war in 1937. But Joe had a war; the war against fascism the war for freedom."

Abe Osheroff, a Lincoln brigade veteran who came to Hanover to show a film he made recently about the Spanish Civil War, said, "There are no beautiful wars. There are beautiful causes." Osheroff, Nelson, and the others who came to the Dartmouth symposium obviously believed as had Dallet that in Spain, in the late thirties, they had found a beautiful cause.

The republican government, now again in power after Franco's 36-year reign, has made available a great deal of new material on the civil war, which was discussed for the first time here last month. They also threw a party for the men who had been there.

Nelson offered the College his thanks for "opening its doors," and a librarian from the official brigade archives at Brandeis University called the seminar "a dream come true." "We don't want to be a place for old documents to collect dust," he said.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTelling Another's Tale

May 1981 By Gregory Rabassa -

Feature

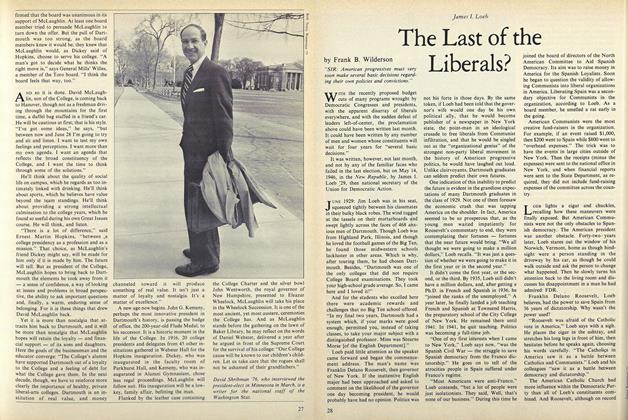

FeatureThe Last of the Liberals?

May 1981 By Frank B. Wilderson -

Feature

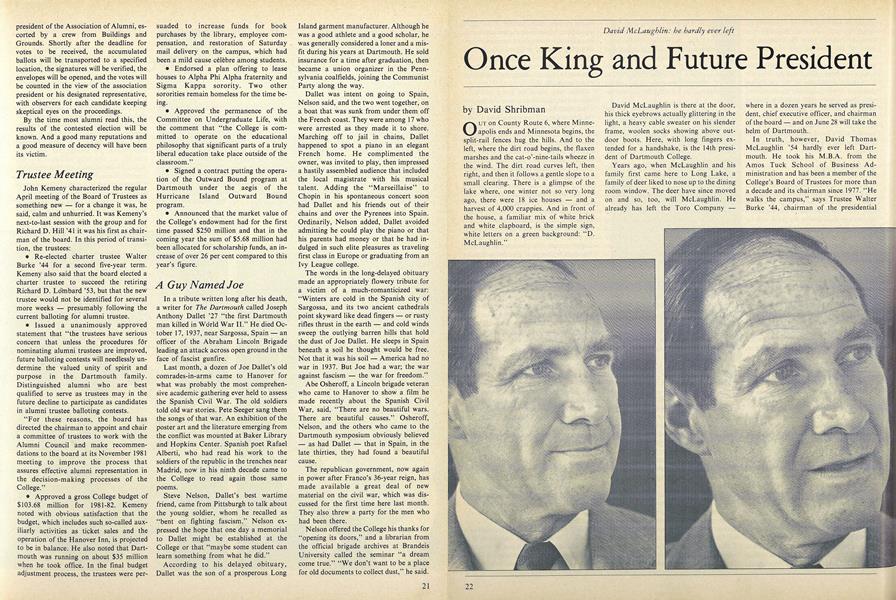

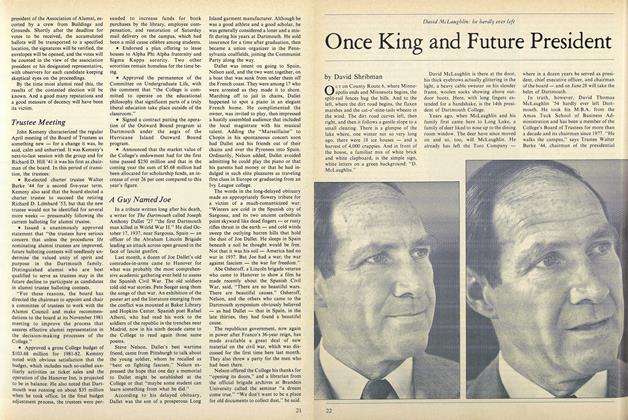

FeatureOnce King and Future President

May 1981 By David Shribman -

Article

ArticleMind for Adventure

May 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues, Etc.

May 1981 -

Sports

SportsThe Club Set

May 1981 By Brad Hills '65