EARLY AMERICANS by Carl Bridenbaugh '25 Oxford, 1981. 218 pp. $19.95

It started as a friendly tavern fight, the kind that has animated American social life for centuries. In this particular instance it was 1766 and the tavern fight had not yet been elevated to the art form it would become in the 19th century, and in Hollywood the principals were Robert Routledge, a Virginia merchant, and Col. John Chiswell, part of the storied Tidewater gentry.

As these things so often happen, the two gentlemen came to disagreement over some minor matter. Chiswell then called Routledge a "fugitive rebel." Routledge threw some wine in his rival's face. Chiswell countered by trying to throw a bowl of bumbo, a candlestick, and a pair of fire tongs in Routledge's direction but finally settled for ordering Routledge out of the room. Of course, Routledge, by now drunk, refused. So Chiswell killed him.

Thus begins Carl Bridenbaugh's tidy little essay, "Violence and Virtue in Virginia, 1766; or, The Importance of the Trivial." It is but one of nine essays about some slice of early American life that, together, make up a tidy little book called, appropriately enough, Early Americans. The essays are about the violent and the virtuous among the early Americans and, as a group, are ample testimony to the importance of the trivial in history.

For in this modest volume, Bridenbaugh's 19th book, one of the nation's most distinguished authorities on early America skirts some of the major themes that he has spent a lifetime clarifying. Instead of the whole canvas, Bridenbaugh this time shows us some of the detail of life in early America the baths and watering places of colonial days, for example, or the associations that organized to spread the ideas of the Enlightenment through Philadelphia and its environs. By the time he is done, he has told us a little about the human side of history. The colonists, after all, were people, too.

In one of his most appealing forays into the sinews of history, Bridenbaugh examines the change in the people who, in 1640, were called Englishmen and who, by 1690, were known as Yankees. Writes Bridenbaugh: "Becoming a Yankee was an unanticipated, unplanned adventure. . . .

The initial experience of the struggle to survive and the haunting sensation of uncertainty felt by most people gave way after a decade or so to a feeling of permanence and hope, and so it continues."

Early America was populated by what Bridenbaugh calls a "migration of superior common people." In New England in particular, they were unusually well educated, skilled organizers, and natural leaders and possessed of a religion that encouraged the kind of hard work and frugality required to sculpt a civilization out of the wilderness. They left a remarkable legacy, and describing how they did it will surely be Bridenbaugh's legacy.

David Shribman is a writer on theWashington staff of the New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

September 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryInauguration of the 14th President: The Spirit of Eleazar Wheelock ... Transmitted through his Successors'

September 1981 -

Feature

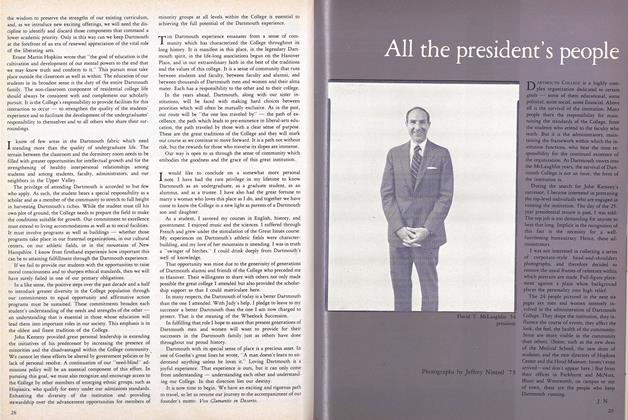

FeatureAll the Presidents's People

September 1981 By J. N. -

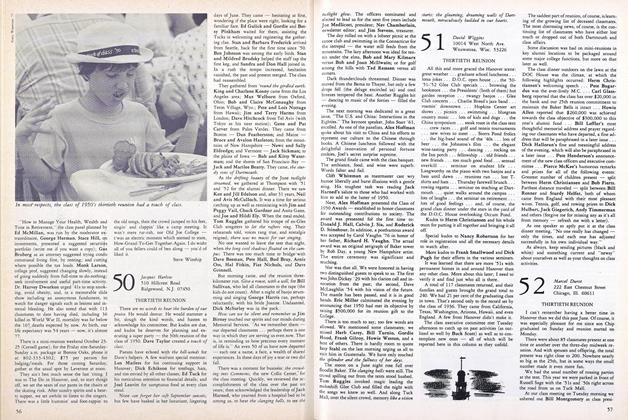

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

September 1981 By Clement B. Malin -

Article

ArticleHistory Without Battles

September 1981 By Beth Ann Baron '80 -

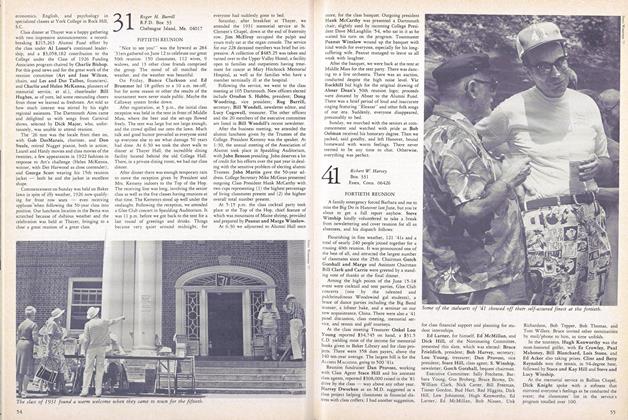

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

September 1981 By Jacques Harlow

David M. Shribman '76

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1983 -

Article

ArticleIn Punt Formation

May 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Books

BooksThis Sceptered Isle

December 1978 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Books

BooksSoiled Pinstripes

October 1979 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

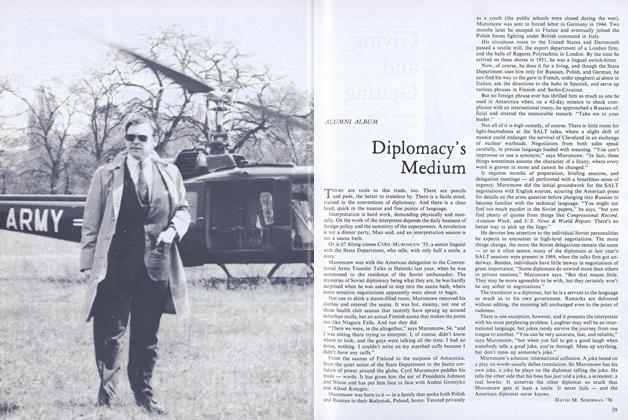

ArticleDiplomacy's Medium

December 1979 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

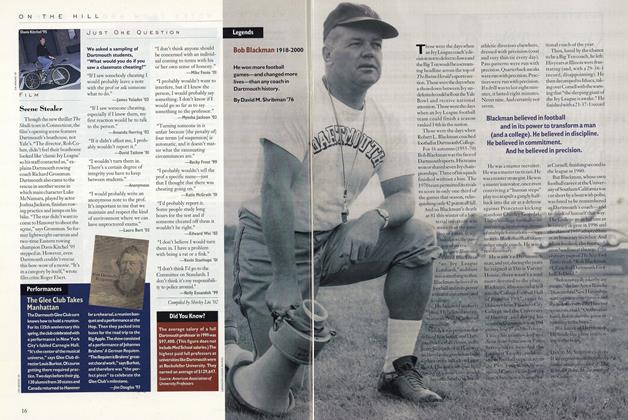

ArticleLegends

JUNE 2000 By David M. Shribman '76

Books

-

Books

BooksPRIVATE ENTERPRISE AND PUBLIC INTEREST. THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN CAPITALISM.

JULY 1969 By CLYDE E. DANKERT -

Books

BooksIF YOU'RE A BANK DIRECTOR

December 1950 By G. W. WOODWORTH -

Books

BooksPower Play

March 1981 By Ian S. Lustick -

Books

BooksBANKERS' HANDBOOK OF BOND INVESTMENT

June 1939 By John W. Harriman. -

Books

BooksTHE TRIAL OF BRUNO RICHARD HAUPTMANN

March 1938 By Ralph P. Holben -

Books

BooksTHE EAST AND THE WEST: A STUDY OF THEIR PSYCHIC AND CULTURAL CHARACTERISTICS.

JULY 1964 By ROBERT J. POOR