It was a scene befitting a classical painting. This was Daniel Webster's final day, his last hours. On this Sunday late in October of 1852, he lay on his bed, the whole grand household, watchmen at the gate of death, at his side. Webster, who had slipped in and out of consciousness all day, knew that death was at hand, and as the moment approached he began to stir. He spoke briefly, in his customary florid way, and then he stopped. "I still live," he concluded, and was silent forever.

Webster's strong sense of the dramatic impelled him to exploit even his exit from this world. Yet in a way, and surely Webster knew this as he slid from consciousness that final time, he spoke the truth. He would live, like Washington, in the national mythology. Indeed, like Washington's, ton's, the Webster legend would take on a life of its own.

Webster would live on in a way peculiar to a man who, like perhaps no other in his generation, personified the nation he helped sculpt. In the passing of nearly 21 decades, when America went from knee breeches to designer jeans, from frigate to nuclear submarine, no man has been painted so often not George Washington, who won the country; not Thomas Jefferson, who invented it; not Abraham Lincoln, who saved it; and not Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who sought to redeem it. Henry Clay, the Kentucky legislator whose, compromises helped put off the Civil War, sat for his portrait 25 times, a number that art historians consider unusually high. Depending upon who is counting, Webster sat between 35 and 40 times.

Having his picture painted became something of an obsession for Webster, who, despite his protests, found the idea of being preserved for posterity compellingly attractive. It was equally an obsession for the artists of the time, who traveled about the country like troubadors in search of a commission or in search of a subject that would attract buyers in Boston, New York, or Philadelphia. In the four years after his famous reply to Robert Hayne on the floor of the Senate echoed across the country "Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!" Webster was painted a half-dozen times. Between 1841, when he became secretary of state for the first time, and 1852, when he choreographed one of the most dramatic death scenes of his day, Webster was painted a dozen times. The portraitists, Webster wrote to G.P.A. Healy, who himself had painted a rendering of Webster's Second Reply to Hayne, were like "horseflies on a hot day brush them off on one side, they settle on the other."

When the National Portrait Gallery set out to mark the bicentennial of his birth this year with an exhibition of Webster portraits, researchers and archivists found a treasure trove. Besides the original portraits, many of which found their way to Dartmouth over the decades, there were hundreds more portraits copied from other portraits, portraits painted after daguerreotypes, portraits painted without a model at all. For years they had hung in hotels, clubs, private homes, even pubs, much the way pictures of John Fitzgerald Kennedy can be found in restaurants and bars now, nearly two decades after his assassination. The proliferation was so great that today the number of Webster portraits cannot even be estimated.

Why Webster was the subject of so many portraits, and why he was painted the way he was, tells as much about him as it does about his time. Though the Webster paintings were intended to help him transcend time, they remain period pieces, themselves sketches of the world Webster shared with Clay, John C. Calhoun, Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Thomas Hart Benton.

A man of words, the greatest orator in the golden age of oratory, Webster also had a special claim to the talents of the portraitists, the literal image-makers of the time. He was a marvelous subject. Washington, Adams, and Jefferson were dead, and Webster, born in 1782, before the Constitution was written, was regarded as the one figure on the national scene whose values could be traced to the Founding Fathers. It was as if the "divine spark" of those few men of genius had been passed on to his soul, where it shined brilliantly. "We understood . . . not only why we have been drawn to him," wrote George Ticknor, a prominent Boston intellectual and fellow Dartmouth alumnus, "but why the attraction that carried us along was at once so cogent and so natural."

For Webster's contemporaries, portraiture was virtually the only way to see a great man. And as the impulse to preserve Webster for future generations grew, the painted portrait was at once the most elegant and, with the exception of the bust, the most enduring form of preservation. When the Boston Athenaeum proposed a sitting for a bust in 1833, its officials wrote: "We are necessarily aware that you fill too large a space in the present generation . . . not to fill hereafter a large space in the regard of posterity. Those who may come after us, therefore, will claim from us not merely a record of your life and labors, but such memorials of your person as may place you before them As you stand before your contemporaries, they will claim . . . not only to know what were your opinions and efforts . . . but so far as the resources of art can embody and transmit them, what were your features and bearing.".

Moreover, Webster, in his lesser-known but equally important, role as representative of railroad magnates and landholders, mercantilists and manufacturers, was wellpositioned to be the subject of a portrait. His constituents, particularly the old Boston ton Brahmins, were, especially posterityminded. One of the reasons Webster was painted more often than, say, Andrew Jackson, was because Webster's allies could afford to commission paintings while Jackson's frontier democrats could not.

Webster spoke to the themes of the age and helped shape the legislation of the time, but he was not simply a spokesman for the Union and for the idea of America; he was a breathing monument to it, a gift, so many of his contemporaries thought, from the ages. His contribution was not as a toiler in the committee rooms of the Senate but as a public man, an actor in the grand theater of the body itself, the floor. Thomas Carlyle, the critic and political philosopher, called him a "parliamentary Hercules." He was often compared to a cathedral, and it is not unusual to find Webster portrayed in a classical manner, sometimes with a bust in the background, sometimes with a globe as a prop.

Indeed, part of Webster's appeal to painters was by virtue of that position he held in American life; artists hoped to establish tablish reputations merely from the fact of having painted him. Hiram Powers, a sculptor from Cincinnati, for example, traveled to Washington with the hope that he might persuade some of the nation's leaders to sit for him. He prevailed with Andrew Jackson and John Marshall and hoped to have the chance to capture what he called Webster's "splendid Head." He was put off so often that he was about to give up when Webster finally agreed to sit on the condition that Powers follow him to his home at Marshfield, Massachusetts, on a congressional recess. Powers assented. As it turned out, Webster fell asleep during the session. Even so, Powers was moved to say that Webster's features reminded him of "Michael Angelo's gigantic statues."

THUS it was not only from the realm of politics that Webster emerged as an attractive figure for painters. As a subject for portraitists he was, in a word, ideal. He was imposing, he was formidable, he was sometimes even frightening. Both his coloring and his carriage lent themselves, almost eerily, to portraiture. In deed and in appearance, he was either the "God-like Dan'l," a favorite appellation, or the agent of the devil. At times, in fact, Webster looked like a historic relic. "His countenance, his figure, and his manners were all in so grand a style that he was, without effort, as superior to his most eminent rivals as they were to the humblest," wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In an age when political candidates are told how to comb their hair and how to select their suits in short, how to package themselves it is startling to look back at a man of politics who was so generously endowed with the tone and tint of statesmanship that he was, if such a thing can be said, naturally packaged. In person, Webster was anything but winning, but in the political arena his appeal was Olympian. Richard Henry Dana Sr., the poet and essayist, once described a rich moment of silence before Webster began a speech: There was, Dana wrote, "an illuminated haze about his countenance, a kind of phosphorescent light . . . arising from internal excitement." George William Curtis, the author and orator, said that when Webster spoke, "his mouth curled, his eye flashed," and he displayed "the restless grandeur of a Titan storming heaven." Seldom, perhaps never, has a major American political figure been so compelling in appearance, so attractive to the portraitist.

Carlyle noted "the tanned complexion, that amorphous craglike face" but, like scores of others, he fixed on Webster's eyes coal-black eyes that burned "like dull anthracite furnaces." In all the Webster paintings, from the earliest portrait to the famous Byronesque "Black Dan" painted by Francis Alexander in 1835, the viewer is drawn almost instantly to Webster's eyes. While Lincoln is remembered for his sad eyes, Webster is remembered for the brooding eyes that darkened as he grew older.

In the first known portrait of Webster, his eyes are open wide. The brows are thinner than they are in the "Black Dan," and the eyes show whiter. In the Alexander rendering, however, his eyes are deeply shaded, with very little white. Four years after the Alexander painting was made, Carlyle described Webster as "a large, grim, tauchy man; as dangerous a looking fellow to quarrel with either in argument or by handgrips, as I have met lately."

That grim feeling comes through even today. Fred Voss, the research historian at the National Portrait Gallery who assembled "The Godlike Black Dan," the Webster exhibition that runs through the end of the year, found Webster forbidding and unlikable. "He was a man who became wound up in himself," said Voss. "He could inspire awe and he could inspire reverence, but he didn't inspire affection. He was not a man who gave himself away. I've been looking at these paintings for more than a year now, and I still haven't developed any affection for him."

The last portraitist Webster sat for was Joseph Alexander Ames, a Boston painter. It was in 1852, the year of his death. Ames captured Webster in a conventional formal half-length portrait and in the fisherman's jacket that he liked to wear at Marshfield. Webster was 70 years old then and, ever willing, knew that there was still talk that he might some day be President. It was not to be.

Webster died soon afterward, but he lingered in the mind of the artist. Less than three years later, Ames unveiled one of the more remarkable paintings of Webster. It was his "Last Days of Webster at Marshfield," showing the broad sweep of Webster's death scene. Across the canvas were the 22 friends and members of the household who were there to watch him pass from life and to hear him declare, with an odd quality of prescience, that Daniel Webster still lives.

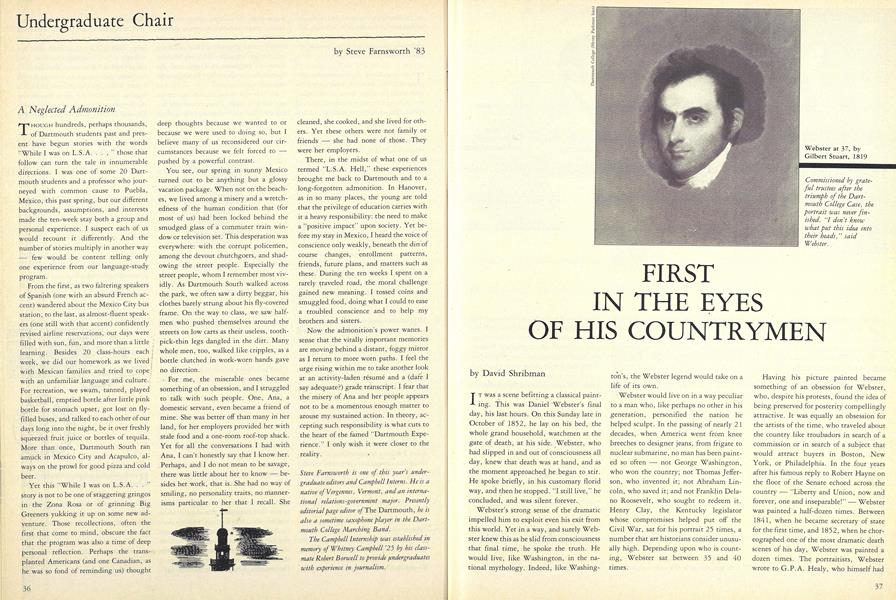

Webster at 37, by Gilbert Stuart, 1819 Commissioned by grateful trustees after thetriumph of the Dartmouth College Case, theportrait was never finished. "I don't knowwhat put this idea intotheir heads," saidWebster.

The spellbinder at 48, by Chester Harding, 1830 Fainted soon afterthe famous reply toHayne, the canvas— complete with anapproving Washington — measuresnearly nine feet bysix feet.

The "magnificent specimen," by David Claypoole Johnson, 1831 "A larger massof brain perhapsnever was, andnever will befound," a phrenologist wrote ofWebster's head.

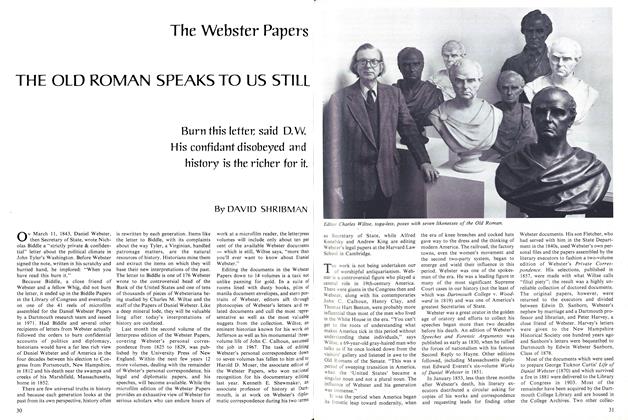

The Old Roman Various sculptorsdepicted Webster inclassic pose — withvarying success.

Replying to I Commissioned for the French court of Louis Philippe, Hayne, by G.P.A. I the picture took some four years to finish. By that tune Healy, 1847 I Louis Philippe had been deposed.

Gentleman farmer at 70, by Joseph A. Ames, 1852 At Marsh field, Ames painted him wearinga floppy hat and fisherman's jacket. It wasjust months before his death.

The end at Marshfield, by Joseph A. Ames, 1855 With as much awe as grief,family and friends keepwatch at the deathbed. Thepainting was finished threeyears after the event.

David Shribrnan '76 is a reporter in the Washington Bureau of the New York Times. Hewrote about Webster in the June 1976 issue ofthe ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

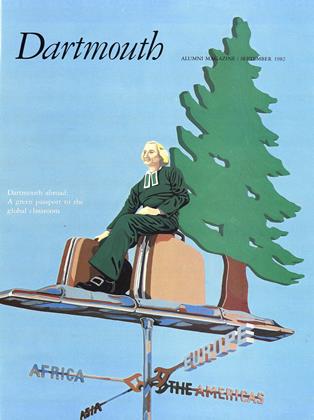

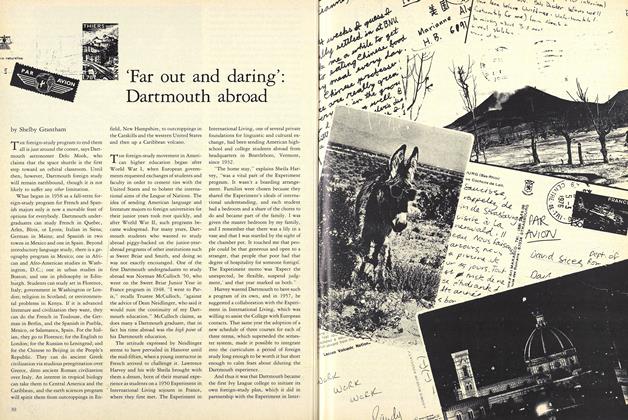

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

September 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Class Notes

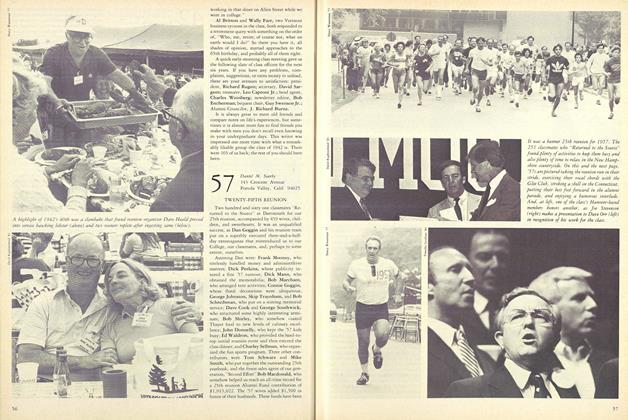

Class Notes1957

September 1982 By Daniel M. Searby -

Article

Article"Man Better Man"

September 1982 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

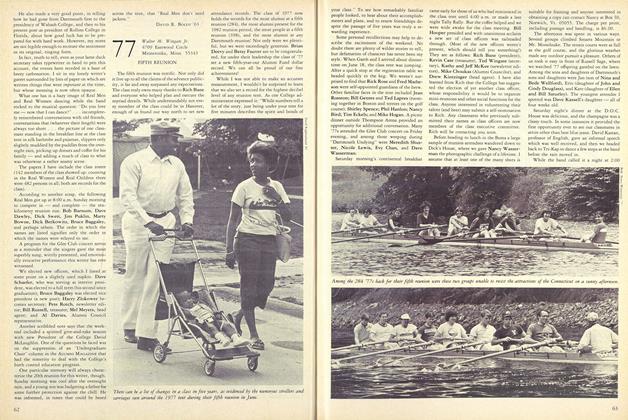

SportsHelp Wanted: Rising Sophomores

September 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1977

September 1982 By Walter M. Wingate Jr., Lindsay Larrabee Greimann '77 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

September 1982 By Richard T. Clarke

David Shribman

Features

-

Feature

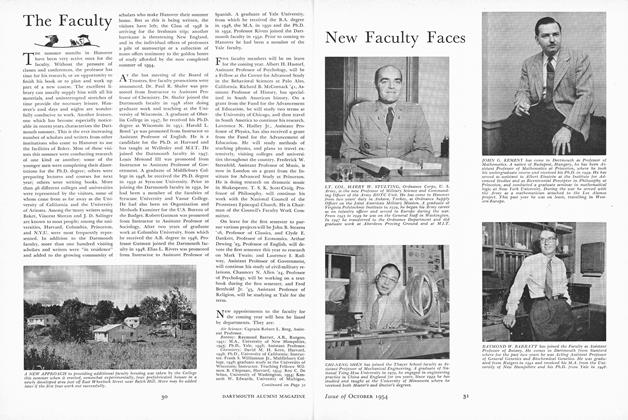

FeatureNew Faculty Faces

October 1954 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHot Seats

April 1981 -

Feature

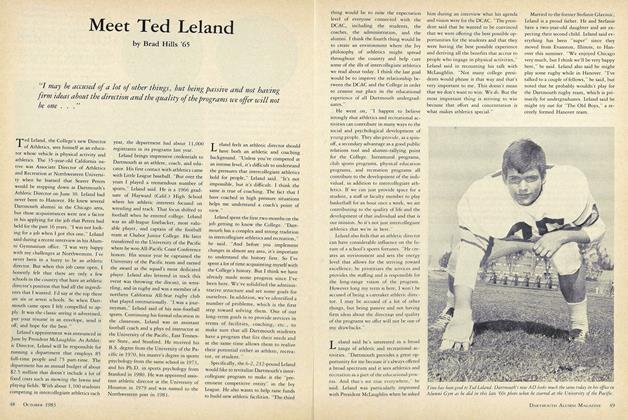

FeatureMeet Ted Leland

OCTOBER, 1908 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeaturePolitics in an electronic age

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Jim Newton '85 -

Feature

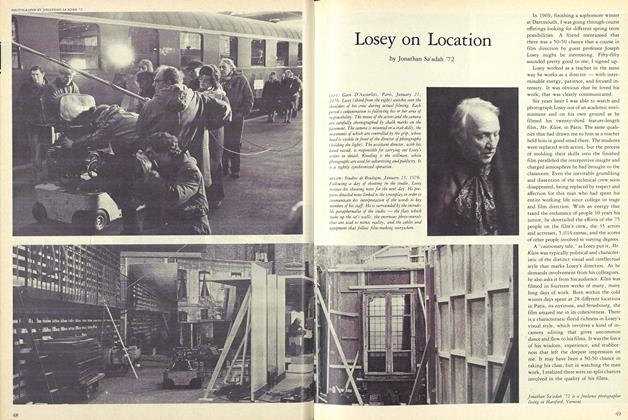

FeatureLosey on Location

November 1982 By Jonathan Sa'adah '72 -

Feature

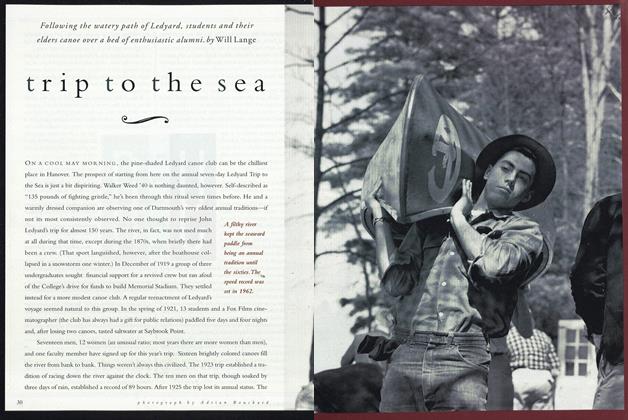

FeatureTrip to the sea

June 1993 By Will Lange