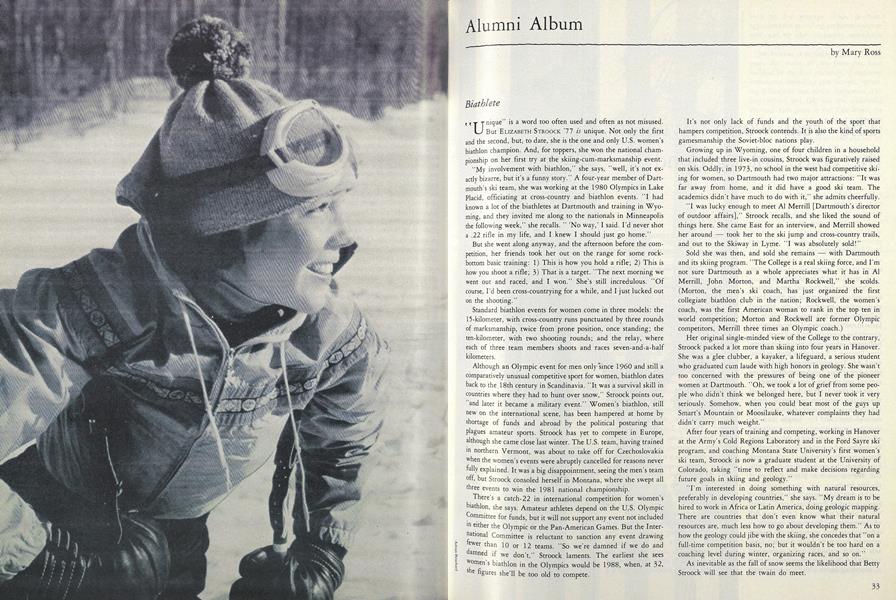

"Unique" is a word too often used and often as not misused. But ELIZABETH STROOCK '77 is unique. Not only the first and the second, but, to date, she is the one and only U.S. women's biathlon champion. And, for toppers, she won the national championship on her first try at the skiing-cum-marksmanship event.

"My involvement with biathlon," she says, "well, it's not exactly bizarre, but it's a funny story." A four-year member of Dartmouth's ski team, she was working at the 1980 Olympics in Lake Placid, officiating at cross-country and biathlon events. "I had known a lot of the biathletes at Dartmouth and training in Wyoming, and they invited me along to the nationals in Minneapolis the following week," she recalls. " 'No way,' I said. I'd never shot a .22 rifle in my life, and I knew I should just go home."

But she went along anyway, and the afternoon before the competition, her friends took her out on the range for some rockbottom basic training: 1) This is how you hold a rifle; 2) This is how you shoot a rifle; 3) That is a target. "The next morning we went out and raced, and I won." She's still incredulous. "Of course, I'd been cross-countrying for a while, and I just lucked out on the shooting."

Standard biathlon events for women come in three models: the 15-kilometer, with cross-country runs punctuated by three rounds of marksmanship, twice from prone position, once standing; the ten-kilometer, with two shooting rounds; and the relay, where each of three team members shoots and races seven-and-a-half kilometers.

Although an Olympic event for men only since 1960 and still a comparatively unusual competitive sport for women, biathlon dates back to the 18th century in Scandinavia. "It was a survival skill in countries where they had to hunt over snow," Stroock points out, and later it became a military event." Women's biathlon, still new on the international scene, has been hampered at home by shortage of funds and abroad by the political posturing that plagues amateur sports. Stroock has yet to compete in Europe, although she came close last winter. The U.S. team, having trained in northern Vermont, was about to take off for Czechoslovakia when the women's events were abruptly cancelled for reasons never fully explained. It was a big disappointment, seeing the men's team off, but Stroock consoled herself in Montana, where she swept all three events to win the 1981 national championship.

There's a catch-22 in international competition for women's biathlon, she says. Amateur athletes depend on the U.S. Olympic Committee for funds, but it will not support any event not included in either the Olympic or the Pan-American Games. But the International Committee is reluctant to sanction any event drawing ewer than 10 or 12 teams. "So we're damned if we do and damned if we don't," Stroock laments. The earliest she sees women's biathlon in the Olympics would be 1988, when, at 32, she figures she'll be too old to compete.

It's not only lack of funds and the youth of the sport that hampers competition, Stroock contends. It is also the kind of sports gamesmanship the Soviet-bloc nations play.

Growing up in Wyoming, one of four children in a household that included three live-in cousins, Stroock was figuratively raised on skis. Oddly, in 1973, no school in the west had competitive skiing for women, so Dartmouth had two major attractions: "It was far away from home, and it did have a good ski team. The academics didn't have much to do with it," she admits cheerfully.

"I was lucky enough to meet Al Merrill [Dartmouth's director of outdoor affairs]," Stroock recalls, and she liked the sound of things here. She came East for an interview, and Merrill showed her around took her to the ski jump and cross-country trails, and out to the Ski-way in Lyme. "I was absolutely sold!"

Sold she was then, and sold she remains with Dartmouth and its skiing program. "The College is a real skiing force, and I'm not sure Dartmouth as a whole appreciates what it has in Al Merrill, John Morton, and Martha Rockwell," she scolds. (Morton, the men's ski coach, has just organized the first collegiate biathlon club in the nation; Rockwell, the women's coach, was the first American woman to rank in the top ten in world competition; Morton and Rockwell are former Olympic competitors, Merrill three times an Olympic coach.)

Her original single-minded view of the College to the contrary, Stroock packed a lot more than skiing into four years in Hanover. She was a glee clubber, a kayaker, a lifeguard, a serious student who graduated cum laude with high honors in geology. She wasn't too concerned with the pressures of being one of the pioneer women at Dartmouth. "Oh, we took a lot of grief from some people who didn't think we belonged here, but I never took it very seriously. Somehow, when you could beat most of the guys up Smart's Mountain or Moosilauke, whatever complaints they had didn't carry much weight."

After four years of training and competing, working in Hanover at the Army's Cold Regions Laboratory and in the Ford Sayre ski program, and coaching Montana State University's first women's ski team, Stroock is now a graduate student at the University of Colorado, taking "time to reflect and make decisions regarding future goals in skiing and geology."

"I'm interested in doing something with natural resources, preferably in developing countries," she says. "My dream is to be hired to work in Africa or Latin America, doing geologic mapping. There are countries that don't even know what their natural resources are, much less how to go about developing them." As to how the geology could jibe with the skiing, she concedes that "on a full-time competition basis, no; but it wouldn't be too hard on a coaching level during winter, organizing races, and so on."

As inevitable as the fall of snow seems the likelihood that Betty Stroock will see that the twain do meet.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe conquest of Kiewit (sort of)

January | February 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe 'real world': Ivies in the cold, cold ground

January | February 1982 By Cliff Jordan -

Feature

FeatureWelcome to the dark places

January | February 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Article

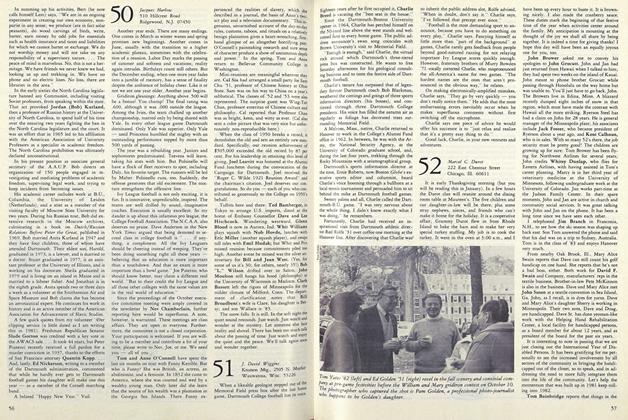

ArticleA Lesson in Survival

January | February 1982 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

January | February 1982 By Marcel C. Durot -

Article

ArticleYoung entrepreneur happy with "inflation"

January | February 1982 By D.C.G.

Mary Ross

-

Article

ArticleTriple-Threat Academician

DECEMBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleTV Journalist

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleMulti-Media Actor

FEBRUARY 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureEditors' Editor

JUNE 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Mary Ross