Any major university gives life to a myriad of phenomena which contribute to an awareness of the world beyond the campus; indeed, such an institution's very existence speaks of the desire to conserve and expand the kinds of knowledge that transcend national boundaries. The sciences and the arts are, in effect, international languages, the humanities deal in ideas which have shaped the consciousness of men and women everywhere, and much of what is studied in the social sciences involves comparisons of systems and cultures and methods in all parts of the globe. In the university community there is bound to be a wide variety of approaches to international concerns and numerous different emphases.

The task of compiling this publication has stemmed, therefore, overwhelmingly from deciding how to choose among so many possible subjects.

In the end the selection was based upon three guiding principles: (a) that people rather than programs should be written about, (b) that "obvious" subjects should be avoided, and (c) that variety be emphasised. Thus there are profiles from the faculty, and in them many distinguished internationalists in history, government anthropology and European literatures were passed over, and such frequently publicised topics as the intensive teaching of foreign languages and the Foreign Study Program are not described again. Observing the third criterion, colleagues from all eight of the main areas of study within the combined faculties wire written up, and they were chosen in order to reflect a range of activities (some of them more "front line" than others) in different parts of the world, undertaken at different points on career trajectories.

Even with all the words in the various essays and profiles, however, the subject of Dartmouth's internationalism is merely opened up; it is not anywhere near exhausted. And so a long final paragraph is added here to remind the reader of some other elements that make up the College's many involvements with the world beyond the United States. Let us not forget: the Orozco Murals; the colleagues who were born in foreign countries and to some extent still derive from their native lands some parts of their life styles (with an Hungarian-American President Emeritus and a Norwegian-American Provost this is one institution which is hardly likely to overlook such a resource); the Dartmouth Film Society and its numerous offerings of foreign films; the many American colleagues with graduate degrees from foreign universities; the flow of distinguished foreign visitors, a resource greatly enhanced by the coming of the Montgomery Endowment; the Thayer School's exchange programs with Aachen and Stockholm; the exotic components of the Hopkins Center's programs, and the work of such professors as Errol Hill in theatre and Bill Cole in music; BASIC; the Chinese Restaurant at the Med School; the forthcoming Ivy League Conference on Issues of Nuclear Arms; the Max- Kade German Center recently given to the College as one of the steps being taken to bring academic and residential concerns closer together; the Reynolds Scholarships, surely one of the most enlightened benefactions to come the College's way, and the begetter of much international understanding within the Dartmouth family; such international scholarly symposia as last year's gathering of physiologists studying the Brattleboro rat; intrepid expeditions by the Ledyard Canoe Club; the Chamber Singers' recent concert-giving tour of England; (and how do we count in such' things as, for example, Richard Eberhart's poetry's being read and Christian Wolff's music's being performed in countries all over the world?); the World Affairs Council; the Chase Peace Prize; the West African-Latin Drumming Ensemble; the brand-new "Global Outreach" initiative proposed by the Undergraduate Council as its response to the challenge implicit in the Dickey Endowment; the world-ranging activities of the Department of Community and Family Medicine; the 1200 alumni living outside the United States; the Grenville Clark Award; the presence of all the flags of the member nations of the U.N. every October 24 and on every Commencement Day, and the United Nations flag itself always atop its flagpole by College Hall.

Charles Hamm, Ph.D.,

Arthur R. Virgin Professor of Music

MUSIC OF THE SPHERE In a piece of not-quite-so-popular-as-it-once-was music, Jimmy Durante, as the Guy Who Found the Lost Chord, used to interpolate a few spoken words: "With my right hand I was playing Tchaikowsky, and with my left hand I was playing Beethoven, and with my right foot I was beating time, AND with my left foot I was cracking walnuts!" Charles Hamm may not have found the Lost Chord, but he certainly emulates the Guy Who did when it comes to versatility and keeping busy.

His teaching at Dartmouth ranges from opera to rock music; his contributions to The New Grove Dictionary include the articles on the Fifteenth Century Frenchman Guillaume Dufay and the very Twentieth Century American John Cage; his books include the best history yet written of popular song in this country; the professional recognition which has come his way includes his having been the President of the American Musicological Society; his array of musical involvements is staggering. This essay deals only with the three most engrossing of his current preoccupations on the international scene.

The most long-standing of these is his research into the popular music of the black population of southern Africa, a study which has taken him to that region twice already and which will involve him in the longest visit yet at some point in the coming year. It is a project which brings him into touch with people and music in Botswana, Lesotho, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. (The other person in the picture is Patrick Buthelezi, music programmer for Radio Zulu in Durban.)

Then comes the work which arose from the June 1981 International Conference on Popular Music Research held in Amsterdam, for which he gave the keynote paper. From that occasion arose his involvement with the International Association which emerged (for the Study of Popular Music), an involvement which has been extensive and brought him the chair of the executive committee in addition to participation in further sessions in Berlin and Kassel as well as at the University of Exeter in England. And planning is moving along for the next full conference; due to take place in Italy in September of 1983; a newsletter flourishes, a world-wide network is being established, and all in all new ground is being broken.

Even more demanding than the I.A.S.P.M. work, though, will be his role as one of the eight coordinators responsible for a 10-volume UNESCO-sponsored publication, Music as a Language of Man: A World History. As the coordinator for North America and Western Europe, no less, Hamm will work with colleagues from Hungary, Saudi Arabia, Ghana, Chile, Vietnam, Japan and Oceania over the next eight years to produce a work which will go further than any previous major study in bringing in all musics for treatment under one scholarly rubric. The assessment of the current state of documentation, the writing of a preliminary cultural-socialmusical introduction to his area, the selection of a group of scholars to write about that area, and the orientation of that set of collaborators, constitute a job of work which is certain to bring to bear upon a massive undertaking the qualities of mind and spirit which have made Hamm one of the most respected men of music of his generation.

One crucial ingredient in the recipe for the admiration in which he is held is the quality which has transformed the Dartmouth Music Department in recent years: a belief that the study of all kinds of music and the making of all kinds of music can and should provide mutual nourishment constantly. It sounds simple and self-evident, but the kind of integration of theory and history and performance and enjoyment which Dartmouth musicians know, is far more rare than one might think. Hamm's catholicity and discriminating enthusiasm for music are, alas, as exceptional as they are valuable; but through the global influence his work is acquiring they will surely inspire many others far from the cramped quarters under Spaulding Auditorium, where the cracking of walnuts can so often be heard.

Timothy H. Hankins '62, Ph.D.,

Associate Professor of Engineering, Thayer School

WAITING FOR THE THAW Tim Hankins is a radio astronomer, among other things, and he has discovered at first hand the inter-relationships between international understanding and professional and personal fulfillment".

Shortly after completing a Ph.D. in applied physics at the University of California, San Diego, he began a long and continuing association with the radio astronomer's Mecca, the radio telescope run by Cornell for the N.S.F. at Arecibo in Puerto Rico. The dichotomy which overtakes any scientist working abroad had begun what's familiar is in the job and what's exotic is in the life beyond the job and so had the expansion of horizons which comes from dealing with it. It was a natural step to involve in some pulsar experiments the three most powerful radio telescopes in the world working in concert, and from Arecibo the most sensitive of all Hankins went to Jodrell Bank in England and then to West Germany, as a Humboldt Fellow, to the Max Planck Institute in Bonn. (By now he was beginning to feel a little sheepish about recalling the scepticism he had expressed to his Ph.D. supervisor regarding the point of retaining foreign language requirements.) An international conference on radio astronomy held in Heidelberg brought him his first contact with colleagues from the Soviet Union and a new chapter had begun. The two Russians had been using a technique developed by Hankins; the three men "hit it off" and a decision was quickly made that an experiment which intrigued them all could best be done on their telescope - in Pushchino, some 100 miles or so south of Moscow. Under a treaty between the USSR and the Federal Republic in effect as a West German Hankins set off with an associate from Bonn to make a series of observations which could only be done in January and February - not the ideal time for much else at Latitude 52°N. But the two months proved to be among the most stimulating and rewarding of his life so far.

With English learned from the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, his Russian hosts and their families (whom he saw almost daily) created an ambience of hospitality, for both work and social life, unparalleled in his experience. The intensity of their Russianness, their commitment to their country regardless of its political system, their joy in their heritage, the patience and good humor with which work was conducted and leisure enjoyed, all produced a sense of their having established an ideal professional relationship coupled with a richly rewarding human encounter.

Then came the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and virtually all contact ceased. Some progress in a specific field of radio astronomy has been killed; some good and brilliant people have had a friendship aborted; and the world is, in some measure, shortchanged.

In research as in life, however, when one door closes another opens. For Hankins the work which has taken over his time since the Soviet experiments had to be abandoned includes a project which needs 24-hours-a-day observation of a particular pulsar in order to look for a "starquake." Which means that observers in two hemispheres must work together: quite soon a radio telescope in Tasmania will look after one half of the day and Hankins will organize the observations which must be made when the pulsar goes beyond the Tasmanian horizon. And so another Dartmouth-Australia link will be forged, and the work of international scientific collaboration will go on.

Robert E. Huke '48, Ph:D.,

Professor of Geography

FILLING THE RICE BOWL Like many another member of his generation, Bob Huke had his first overseas experience under the auspices of the United Ssates Marine Corps. In his case it led to a life-long involvement with a distant continent, for the fascination with China which was sparked when he was a serviceman led directly to his electing a study of irrigation in Szechuan province as his Syracuse University Ph.D. topic just in time to suffer the frustration of seeing the Bamboo; Curtain descend and make contact impossible. But similar Work could be undertaken in Burma, and a lateral move from irrigation to a study of agricultural land use and the economics of villages in that country led to both a doctorate in geography and the subject that has engaged some part of his attention in all of the thirty years since the cultivation of rice, the world's most important single food crop.

Huke is by now one of the senior researchers working out of the International Rice Institute at Los Banos in the Philippines, his association with which began when, in 1955 and 1962, he held Fulbright Professorships at the University of the Philippines. From his frequent visits he has been able both to concentrate on changes in one place (his article "San Bartolome and the Green Revolution' and its sequel ten years later "San Bartolome Beyond the Green Revolution provide an invaluable picture of development in a single small community), and at the same time to become expert in comparative studies of rice production in many far eastern countries. Just one mapping project, in which Dartmouth undergraduates were involved, incidentally, took him to Bangladesh, Burma, India, Thailand and Pakistan.

That 1979 expedition led to an exceptional experience. A year later Huke had the opportunity to lead a 14-member team on a study of rice agriculture in the People's Republic of China. It brought with it, at last, the chance to visit the place which was to have been the object of special study as a graduate student the oldest continuously working irrigation system in the world, a system that has not been known to fail once since it was built in 256 B.C. A 2000-year-old technology had something to teach a group of people possessing knowledge derived, from the very latest research and study.

The 1979-80 South Asia mapping project has opened the way to a yet more intensive study of one of the countries surveyed then, Bangladesh, and to a venture that will link, in a sense, two Hanover research institutions, for Huke's collaborator in the early-'83 work will be his wife Eleanor, a cartographic technician at the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratories of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. If all goes well in Bangladesh, 1984 will see the launching of a more detailed survey of Thailand.

It is, in one respect, a long time since the moment when a life-changing interest was sparked in geography classes in Huke's senior year at the College an interest, as he puts it, in the concept of man's organizing the space around him but relative to the Chinese irrigation system, his journey began just a few days ago. When you ask him if there's any danger of his running out of rice-related work in the "days" ahead, the answer bursts out in a split second: "Oh God. No Way."

Gary D. Johnson, Ph.D.,

Associate Professor of Earth Sciences

THAT GUY'S NOT JUST COLLECTING ROCKS." In the course of the conversation, A Gary Johnson pauses, looks into the distance and says "You know, it's a humbling experience." The interesting thing is that he is not talking about his research, although one might well think that establishing the exact chronology of the formation of the Himalayas is work which would bring a sense of how small one individual life is when seen in the context of the history of a mountain range. The fact that the humbling experience is what comes from living among the people in northern India and Pakistan is the thing which catches one's attention, because, after all, this was to be a conversation about geology.

Geology is certainly talked about. It is bound to be, considering that at least four members of the faculty of the Dartmouth Earth Sciences department are actively engaged in the Himalayan work, that at least a dozen senior theses and as many for the M.A., as well as half-a-dozen Ph.D. dissertations have come out of it, and that the College's association with Peshawar University in Pakistan is one of the most successful foreign institutional collaborations of its kind. But it is when the conversation goes beyond such matters that one reaches an understanding of a comment made about Johnson by a colleague in an Humanities department: "That guy's not just collecting rocks."

It is very clear that a significant part of what is valuable in the annual expedition to what begins to seem like a second homeland is the opportunity to renew contact with a culture, and an annual reminder. It is the reminder of the humbling experience of having discovered, after twenty-odd years of taking it for granted that the world revolves around the United States and its foreign policy, that millions of people are utterly indifferent to the very existence of any country, any culture, any way of life other than those they and their ancestors have known; and that from their point of view it makes not the slightest difference what anyone in Washington thinks or does.

To intensify that valuable lesson for all the Dartmouth visitors, and because "the effectiveness of this kind of scientific work is directly proportional to the distance from the nearest urban center," everyone has little contact with the places on the normal tourist circuit, and lives instead in government guest houses, or tents, or as paying guests in people's homes, in villages where the mean annual income may be as low as $60.00. The effects of sharing a very different kind of life, especially in a country living under martial law, especially one which is subject to the manifestations of the traditional Islamic social attitudes, can be very great indeed. Johnson recalls more than one occasion on which a student has wept as the plane bringing everyone home has touched down on American soil, moved by the sudden reminder of how much in terms of freedoms and opportunities is to be found here, and is unobtainable from so many different reasons to so many other people.

It is hardly surprising that one of the concerns which engage Johnson's attention these days is the way in which "First World" diplomats, perhaps Americans more than others, seem to see more of other diplomats than they do of the people, the ordinary people, of the countries to which they are assigned. He and his students and colleagues share experiences which "our diplomats may never have," times of interaction with the indigenous population in which considerations of nationality, politics or economics, even of culture and religion, all break away, and the commonality of people sharing hardships and facing challenges gets ahead of everything else.

William Luis, Ph.D.,

Assistant Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Languages and Literatures

A SENSE OF RESPONSIBILITY Like great whales who live on minute particles of plankton, mighty events incorporate all the tiny repercussions they have on the millions of individual lives they affect. Fidel Castro's overthrow of the Batista government in 1959 was to change the dynamics of the western hemisphere tor ever, but for William Luis, in grade school, it mainly meant that visits to his mother's family in Havana came to an end. At least temporarily.

The child of a woman born in Cuba and a man born in China, growing up bilingual in the cosmopolis of New York City, majoring in history and Spanish at S.U.N.Y. Binghamton, Harpur College, Luis had at least one eye on the distant horizon almost from the beginning; but it was not until he was a doctoral candidate at Cornell that he began to look at Cuba. Since then he has become one of the leading American authorities on serious writing by contemporary Cubans, both on and off the island, and was recently appointed by the Library of Congress to serve as Contributing Editor of the Hispanic Caribbean section of the Handbook of Latin American Studies. His interest in contemporary literature has led, inevitably, to his becoming something of an expert also on Cuban and Caribbean literatures of earlier times; and, just as inevitably, a student of the interplay of literature and history, literature and society, literature and politics.

In December of 1977 Luis was a member of the first group of Cuban-Americans to be allowed to visit post-revolutionary Cuba. He has been back every year since, including the time when he directed a cultural trip, in March of 1981, tor Dartmouth students, faculty and staff. In addition he has been to conferences of Caribbean studies specialists held in Haiti and the Bahamas. Although he travels for research, the rediscovery, twenty years further on, of family ties brings an intensity to the experience which is by no means a common phenomenon among scholars.

A lot of Americans get emotional about Castro's Cuba; indeed the subject seems to be one which touches a uniquely tender spot on our body politic. But the emotion which Luis manifests when talking about his work is very different from the common outrage and bewilderment over the loss of a favorite step-child. His is the emotion of someone who is privileged to be both involved and detached, enthusiastic and analytical, at the same time. Above all there is the excitement which comes from knowing that he is studying a reality which is very complex indeed and studying it from a unique vantage point.

One of the fascinating aspects of the study is the fact that so much of the Cuban experience before 1959 was written from the point of view of a society in transition which lacked a complete vision of the past and future, and not one which has arrived and has, therefore, a sense of its destiny. Cubans ot today are bound to re-interpret the past whenever they write about it, imposing something on it at the same time as allowing the past to emerge from what they write. It is, as Luis says, very revealing of the political intent of past and present societies, and very demanding upon the critic and literary historian.

Another thing which can keep him busy and on his toes is examining the paradoxical situation in which the revolution both stimulated and undermined literary expression. Before 1959 relatively little serious writing, and not much more serious reading, was going on in Cuba. The revolution, at least initially, provided an impetus to writing and, through its disregard of international copyright agreements, made available inexpensively a great deal more to read. But there was, and still is, a price to pay: and Luis's areas of study include the tension created by a new freedom and a different form of repression. One battleground about which he is an expert is Lunes de Revolution (1959-61) the literary supplement of the official newspaper Reuolucion, in whose editorial policies Castro himself made his authority felt; a magazine of genuine importance in Latin American and western cultural studies. The conflicts surrounding Lunes set the stage for the ambiguous position of many intellectuals.

One thing about which there is no ambiguity, however, is the sense of responsibility Luis feels towards his current preoccupations. He is in something close to a unique position to do justice to the subject, and even though broader issues are opened up by the study of the literature of one small island in the sun, they cannot pre-empt, not yet at any rate, that central inherited concern.

Donella H. Meadows, Ph.D.,

Associate Professor of Environmental Studies

THE VERY MODEL OF A MAJOR MODERN GENERALIST - ln 1968 Dana Meadows received her Ph.D. in biophysics from Harvard and her husband got his in management from M.I.T. They decided that before settling down to their respective projected careers, she figuring out more about how enzymes work, he helping some company or other to make money, they would spend a year in Asia, unwinding, climbing, kayaking, and generally getting ready for the next stage. Everything went according to plan, except that the next stage proved to be, as it were, in a different theatre. What they discovered was poverty, hunger and the mishandling of resources on a scale which simply obliged them to see the world, and their places in it, through new eyes. Within a month of returning to the United States they had not only found their "dream project" but had become a part of it: the Club of Rome study at M.I.T. which produced the controversial but unignorable report on the world's predicament, The Limits to Growth.

In the year that book was published, 1972, Dana and Dennis Meadows joined the Dartmouth faculty and her influential career as a teacher began. A part of what makes it important in the lives of so many students is her ability to relate to both the global and the local, the cosmos and the microcosmos. One does not spend much time finding out about international good works before discovering that there are those who see their mission as the digging of ditches, and others who see their role as negotiator at the international congress of some high-powered agency or other. Many people, in fact, confine their work to one or the other arena because that is how their talents are best used, but others have the experience and the temperament which enable them to move between the two kinds of work and to relate them to each other. Dana Meadows may be more comfortable helping with the lambing than talking with dignitaries over cocktails, but she is adept at both tasks and enjoys the gobetween role and what it can accomplish.

The same truth applies to the range of what she teaches and studies. People who know her well speak admiringly of the fact that she really does see the whole world as the society which interests her and with which her work must inter-act; and such commitments as the Hunger Project (a non-profit corporation dedicated to the realizable goal of ending hunger in the world by the year 2000) and the course she teaches on environmental ethics reflect her passion for dealing with the large issues. But she also gets into the nitty gritty of such things as zoning ordinances and shepherding her students through the making of a major analytical investigation of the potential effects of siting a pulp mill in the Upper Connecticut Valley. And it is evident that her professional life is nourished by this moving back and forth between the great issue and the particular problem.

That life-changing year in India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka can never be repeated, but travel abroad has been a part of every recent year, three or four expeditions at least, sometimes as consultant, sometimes as participant in conference or congress or workshop, sometimes as evaluator. Wherever she goes she takes with her a disarming directness, a quality reflected in the introduction to the most recent book on which she has collaborated, Groping in the Dark: The First Decade of Global Modelling. In a section entitled "The Editors' Biases" the following characteristics are given to tell the reader who Dana Meadows is: "cares about and worries about the long-term future of mankind; is militantly interdisciplinary; values nature and the arts; tends to be workaholic; sees the world through the paradigm that there are paradigms; believes that the world is made of complex systems that we cannot understand intuitively; dislikes big centralized systems, including modern capitalism and communism; favors system dynamics as a modelling method; lives in a commune, raises organic vegetables, jogs, and heats with wood; studies Zen Buddhism and therefore knows that there is such a thing as Truth, that it can be found within oneself and not in the world of illusion, and that it is not easy to find; believes that all people arc truly magnificent, that the world is a precious miracle, that the future could hold either unspeakable horrors or undreamed-of wonders, and that it is up to us." What more can one say?

James Brian Quinn, Ph.D.,

Buchanan Professor of Management, Tuck School

R& D AND WORLD NUMBER THREE Much of his professional life has been spent at the Tuck School, but at the same time he has worked everywhere, worked in four of the five continents (so far he has only visited the fifth, Africa, as a tourist), worked on two-way streets.

Brian Quinn's expertise is in understanding the nature of "R & D" and evaluating large institutions' approaches to it. Especially on the national level, in science, technology and economic policy, the soundness of Research and Development strategies can make the difference between hope and chaos; and degrees in engineering from' Yale, management from Harvard, and economics from Columbia give a person a chance to see the wider picture. In countries as disparate as Nepal and Norway and Peru, Quinn has brought criticism and advice to bear upon various governments' views of what makes sense for their respective country's future. And as a member of the National Academy of Sciences Board on Science and Technology for International Development he is likely to find himself kept busy at that kind of work.

At the same time, there are other things which take him abroad. He writes case histories, for example, on how major breakthrough products and processes came into existence things like Hovercraft and Float Glass and that means going to Britain, France, Japan or wherever the people are who have the breakthrough story to tell. Almost every summer sees him back in Geneva at the International Management Institute matching his wits with high level executives from all over the world. Individual companies and government groups in many countries like to have him present seminars on managing technology strategies. Not so long ago he spent a term as visiting professor, on a Fulbright Fellowship, at Monash University in Australia, lecturing at most major universities there. It all adds up to a lot of potential for furthering international understanding.

Ask him, though, to tell you when he was most.keenly aware of being in a world different from home, and the talk turns to the biggest country of them all, the People's Republic of China. He has been there three times now for extended visits twice on government missions exploring the establishment of connections in business and commerce, once in his favorite role, as teacher.

The Chinese learned to play the kinds of computerized business "games" American management students and executives take for granted, but with a difference. One totally unexpected complication came when, having divided his students into three groups which he called "worlds" (each of which was further divided into ten teams), he found that the people in World III thought they had been put in a disadvantaged "Third World" from the word go. Another surprise was the grandiose scale on which everyone conceived their physical plant expansion, with no reference made to realistic planning or projections for what might happen to what they turned out. There were others. But the moment that told Brian Quinn that he was dealing with a basic, one might say a cultural, difference came when every single team, all thirty of them, failed to meet the established deadline for submitting answers. Time is seen differently depending on where you are.

So one sees a lovely paradox in Quinn's involvement with the larger world. On the one hand he felt that his responsibility to his Chinese hosts required that he instill in them an understanding of new technologies and the personal discipline they involve. On the other is the increasingly strong sense of regret he feels that the corners of the earth's surface where one can have a sense of timelessness a glimpse of the Eden the earth once was are fewer and fewer in number with each passing year. He is one man who is glad to have been born when he was and to have been moved by those that remain.

James C. Strickler '50, M.D.,

Professor of Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School

HANDS ON Of the men and women profiled in this section, the one with the closest sense of identification with the Dickey Endowment is probably Jim Strickler, for he has no doubt about the impact upon his sense of the world community which came from his experiences at Dartmouth in the early years of John Dickey's presidency. At the very end of World War II a stint in the U.S. Maritime Service had whetted an appetite for learning more about the world he had glimpsed, and this curiosity was nurtured and increased by the Dickey vision, embodied in the Great Issues course. He still has vivid memories of the people, many of them from abroad, whose visits to the College deepened and widened his acquaintance with that global arena in which a new United States was beginning to assume the role of superpower. It is no wonder that he has a from-the-heart belief in the potential which the Dickey Endowment has for restoring such concerns to a central place in the life of the College.

After Dartmouth, medical school and years spent in the clinics and hospitals of New York City, itself another world, there followed an eyeopening stretch of time as a naval doctor on ships stationed in the Western Pacific, a world very different from that about which Rodgers and Hammerstein were writing. Here was the inescapable fact of the primitive state of health care in places remote from centers of commerce and power. The sight of foot-powered hand drills at work on decaying teeth makes an indelible impression. So does one's first awareness of shortages of every kind, methods of treatment decades behind those one has just learned, and the realisation that in other parts of the world high expectation is an almost unknown commodity.

For several years the concern lay dormant, but with his appointment to the deanship of the Dartmouth Medical School in 1973 the beginnings of a personal response took shape. Many people must contribute to any significant academic planning, but Strickler knows that he can take some of the credit for the emphases which have become important at the Med School in recent years emphases on health care delivery in non-urban situations, on the development of para-medical education, on the creation of unique relationships with other institutions. And he. can take satisfaction in the knowledge that these developments all help create doctors who can adapt, more readily than most, to serving in underdeveloped countries, if they choose. Visits to Tunisia for USAID and to China strengthened a conviction that international involvement was not only desirable but someday inevitable.

After leaving.the deanship in 1981 he took about as big a step as a person could take while remaining in the same profession: he exchanged his office in Remsen for a field clinic in the Khao-l-Dang refugee camp in Thailand. The largest in South East Asia, with 45,000 people in an area of six square kilometers, only five kilometers from the Cambodian border, this camp provided not only the reawakening of a front line doctor's burden/joy of primary health care delivery, but also an opportunity to serve as an expert reviewer of administrative problems in the treatment of refugees all over the orient.

That extraordinary work over, a return to Hanover brought new involvement with overseas problems. He is only just recently back from Beirut and a study for the International Rescue Committee centering on Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, and he is likely to find himself as fully occupied in similar work as his responsibilities as a full-time member of the clinical teaching faculty will permit. But another Lebanon has a claim on his time, the one just down the road from Hanover, where a family practice center gives him the chance to continue "hands on" work as "just a doctor."

The Great Issues do not change and do not go away: how will highly educated people most responsibly use time and talent; how can this richly endowed country of ours best help the rest of mankind; how are priorities to be set in situations where the resources are far from sufficient to meet every need? Jim Strickler's 35 years of confronting Great Issues make him an unusually good teacher for those who are encountering them for the first time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

December 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhere They Hang Their Hats

December 1982 By Steve Farnsworth and Jean Korelitz -

Feature

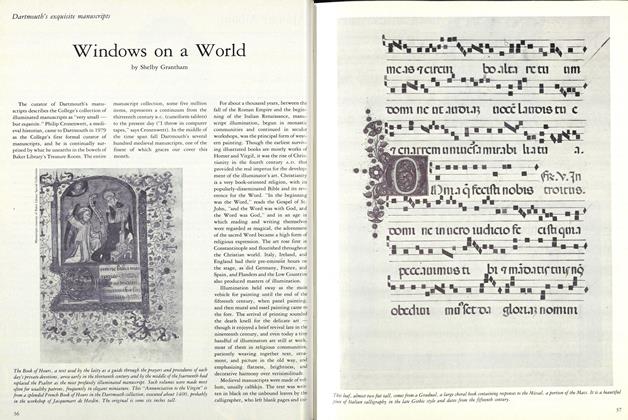

FeatureWindows on a World

December 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleRound the Girdled Earth...

December 1982 -

Article

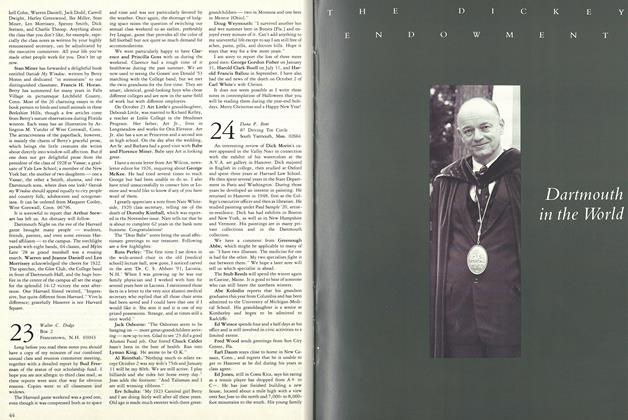

ArticleTHE DICKEY ENDOWMENT

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleOff to a Good Start.

December 1982 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47