The publication of this booklet celebrates the launching of the John Sloan Dickey Endowment for International Understanding at Dartmouth College, and invites the entire Dartmouth family to reflect upon the perfect appropriateness of the means chosen to honor John Dickey's presidency. It will also make the reader aware of an important fact about Dartmouth: the Dickey Endowment responds to a situation in which much has already been achieved in international bridge building, but from which much more could be brought to life if only the means can be provided.

If the College were starting something of this magnitude without having the ground so well prepared the initiative would seem grandiose and the challenge formidable; on the other hand if the College were already doing everything that any college could do in this field the Endowment could appear superfluous. Just as it is exactly the right program for the man it honors, so it is exactly the right moment for strengthening the work which has always meant so much to him.

In order to suggest both what has been achieved and what is possible, a relatively formal statement of purpose is followed in this booklet by a description of the activities marking the announcement of the Endowment and by a series of essays about men and women who exemplify "Dartmouth in the World." But before everything else come some words about Mr. Dickey himself; they would be desirable in any event, but they take on extra significance because more than ten thousand men and women have matriculated at Dartmouth since he retired from the Presidency, and it is especially good that they be given of the quality of the man whom most of them never had a chance to meet. Two other items complete the publication: a map which indicates the scope of the College's worldwide associations, and a list of the countries in which members of the four faculties have worked in recent years.

John Dickey has a wonderful way of putting words to work: a phrase from his 1963 honorary degree citation for U Thant described the third Secretary-General of the United Nations as"one who bears the heaviest teaching load of all." President Dickey has suggested in many ways that life may be seen as largely a matter of teaching and learning, learning and teaching, and he has made it abundantly clear that the profoundly valuable work of fostering international understanding offers a constant flow of opportunities for both. For Dartmouth men and women in the coming years the Dickey Endowment will make possible a greater awareness of just how numerous, challenging and rewarding those opportunities can be.

Hundreds of men and women would welcome, and make good use of, the chance to write a tribute to John Dickey, and choosing among them would be invidious indeed, were it not for the fact that a distinguished and very exclusive group of people suggests itself as those who should be asked. There are more living recipients of Dartmouth honorary degrees in the Class of 1929 than in any other class; one of them is Mr Dickey himself the other four have been so kind as to put their reflections about him into words. They speak for all of us.

John Dickey's personal attributes are well known to the Dartmouth family: a warm heart, scrupulous honesty, curiosity, enthusiasm, inexhaustible physical and mental vigor and a wit and sense of humor that never bit anyone except, occasionally, himself. As a friend, I find no words to bear the burden of his praise.

I would speak, however, of his accomplishment in leading Dartmouth to the top rank among the world's educational institutions and use as a measure of his achievement a standard proposed twenty-five hundred years ago. A leader, said Pericles, must be one who can see what ought to be done, can explain what he sees, who loves his city and who is above being influenced by personal gain.

It was the dawn of a new age when John Dickey became President of Dartmouth on November 1, 1945, but the College had not recovered from the effects of the war. It had been part of the United States Navy for four years. Some of the faculty had gone off to war. The ones who remained in Hanover had devoted four years of uninterrupted effort, far beyond normal academic burdens, to the instruction of officer candidates often in subjects outside of the teacher's area of special competence. Much maintenance of the physical plant had been deferred.

The new President saw that his first priority was to renew and strengthen the faculty. The fact that one of the recruits became Dartmouth's thirteenth President is an example of how well this was done. Concern for academic quality became a hallmark of the Dickey administration. Although Presidents Tucker and Hopkins had been almost combative in drawing the distinction between Dartmouth as a liberal arts college and a university, Dickey capitalized on Dartmouth's good luck in happening to have three graduate schools long before he assumed office. He saw in the depth and rigor of graduate programs a contribution to the undergraduate experience.

There were also other important and far reaching things to be done. He saw them at the beginning and he pursued them for the next twenty-five years. The first of them was to foster at Dartmouth a wider view of the world. Dartmouth in the early decades of the twentieth century was a more isolationist place than it was in the last decades of the eighteenth century. The Great Issues course for all seniors not only helped each man to identify more closely with his class but it also expanded his horizons. The great convocations of 1957 and 1960 reached out to the whole English-speaking community.

A strong moral and spiritual emphasis always was and is part of Dartmouth. Except for John Wheelock the Presidents of Dartmouth from 1769 to 1909 were clergymen. The moral elements in a liberal education never had more effective expositors than President Dickey's predecessors Dr. Tucker and Mr. Hopkins. John Dickey's creation of the Tucker Foundation continued a great tradition. Good and evil exist, he asserted, and it is the duty of virtuous men to choose the good. He often returned to the theme that competence and conscience go together and the value of each is diminished without the other.

Nourishing spiritual roots, opening windows on a larger and closer world and scholarly achievement are only three of the goals that John Dickey identified. There were many others.

Having decided what had to be done, how well did John Dickey go about getting it accomplished? He soon demonstrated remarkable skill in explaining to others what had to be done and getting them to do it. He was not only punctilious in assembling all relevant facts before taking action but he also made sure that the people who would be the actors in policy were also 'participants in the research that supported it. The volumes of planning committee reports of the 1950s and 1960s are evidence of how well this job was done.

He so managed the trustees, expanded in number during his administration from twelve to sixteen, that cliques, cabals and intrigues never occurred. The cards were always put down face up. Every major policy decision during the Dickey years was voted unanimously, a record without parallel in the history of the College.

As for what Pericles called patriotism or loyalty, no one could have more wholehearted devotion to Dartmouth than President Dickey. His passionate affection embraces not only the people who are Dartmouth but also the woods and mountains and streams around the College. He has spoken often of the importance of place in binding the heart strings. President Dickey led a heroic administration in the classic mold all of which I saw and part of which 1 was.

Of course I was aware of john Dickey as an undergraduate, but he was a little older than I and in a circle quite apart from mine. So, while we were friendly, we didn't become friends until later in life.

I saw something of him during his days with Nelson Rockefeller when they were working with the Roosevelt administration on South American affairs. I really only got to know him when I was teaching at Dartmouth in the seventies.

Even as a young man it was clear that he had a destiny of importance and that it would probably have some connection with the College. His strength and integrity were evident. To me, he was then and is certainly very much a father .figure, one of those rare people to whom one can look up. His strength was always evident, and his contribution to the College, as well as to every individual he encountered, is equally evident.

Strangely, this very fact makes adjectives seem fulsome. John Dickey is one of those rare, lucky men who has completely accomplished and fulfilled an important life, which, if it isn't too mystical to say, was pre-destined. Everyone who has known him, even from a distance, respects and loves him.

I clearly recollect knowing John Dickey during our first undergraduate years at Dartmouth, and I remember Chris, too, when she worked at the circulation desk in the old Library (now the College Museum). We did not see much of each other in our last two years at Dartmouth, nor for some years thereafter, though we occasionally met when he was at Harvard Law School and I was spending a semester as a graduate student in the Harvard Philosophy Department.

What comes, back most forcibly, however, was a speech he gave Alumni Club in Philadelphia shortly after becoming President. I was teaching at Swarthmore at the time, and was becoming somewhat restless. The theme he sounded was one of Dartmouth's social obligations, and his desi're to make it, more than ever, a training ground for leadership in service. The following year I was on a Guggenheim Fellowship, and chose to spend it in Hanover. We saw something of each other during that year, and I was delighted when I was invited to join the faculty, which 1 did in 1947.

John and I saw a good deal of each other on and off, frequently on occasions when there were visiting philosophers in whose work he too was interested. I remember particularly a discussion with Reinhold Niebuhr in the President's House, and two vivid discussions in my own living-room with friends who were up for Great Issues talks and had a direct interest in the Hiss-Chambers case.

1 tend to identify the best in John Dickey's administration with that course, with the spirit which had given rise to it, and which it successfully fostered over many years. I hope that succeeding generations of Dartmouth students will emulate those and there were many who during that period laid the foundation for the distinguished careers which they have had in service to the public. Given this heritage of John Dickey's stewardship, no other memorial of his Presidency could be as fitting as the one which the Endowment proposes.

John Dickey is apt to characterize me as the most successful conservationist ever to set up an ambush in a duck blind. Although this may be more than poetic license, it cannot be charged against him as a gross misrepresentation since it is a judgment resting upon more than thirty-five years of being witness to the fact. For, as the years sped by, the duck blind in the marshes beyond the northern shores of Lake Champlain became less and less a place for dead-eyed wing shooting and more and more a place for the sharing of Dartmouth. Much—very, very much of my Trustee service to the College has been founded upon the institutional purpose and the values and qualities of the human spirit learned from him as we sat huddled on sheltered stools on the edge of a wildfowl pot hole principles and philosophies declared and debated, discussions that even an approaching flight of ducks would not interrupt.

Each of us in our own way, as well as our beloved College, has been enriched by John Dickey's extraordinary humanity and joie de vivre that inspired his Dartmouth Night prediction that "you and the oncoming generations of Dartmouth men will not miss the joy. It is yours for the keeping." Dartmouth is the work of many men, the magnum opus of none. But among the many who have devoted the better part of their lives to her building, John Dickey will always stand high in the ranking.

His deeds will have no recital here, nor should they at this time when it comes so hard, even now, to find "the words to bear the burden of our praise" for the quality of the human spirit that bred the goodness with which he has always graced the College and with which he will endow her forever. Yet, this is a time for everyone and everything that is Dartmouth - is place, this College, the increasing host of freshmen become "Dartmouth men" to cherish the rare confluence of his uncompromising integrity and his gentle, understanding strength that has sealed for so many a commitment to conscience as well as to excellence; a time, also, to bear witness to the pervading sense of gratitude, love and pride for this man whose lifelong dedication to the highest aspirations of the College it will be our honor to sustain and strive to enhance.

The John Sloan Dickey Endowment for International Understanding will honor the values and achievements exemplified in President Dickey's lifetime of service to the causes of international cooperation, liberal arts education, and scholarship. Few individuals have embraced the scope of accomplishment or exhibited the high standard of values and capacity for human understanding that John Dickey has displayed. In its simplest terms, the Endowment's programs will seek to promote these same values among all Dartmouth students.

As its foundation, the Endowment will encourage on a sustained basis, both within the curriculum and through extracurricular programs, a process of learning that emphasizes an understanding of diverse cultures and systems of government. Programs supported by the Endowment will expand our capacity to empathize with those who think and act differently, to communicate comfortably with persons from other cultures, to gain an understanding of the processes for addressing the great issues that divide nations, and to use constructively, as well as with sensitivity for traditional values and systems of beliefs, the opportunities inherent in new technological developments.

By promoting these goals the Endowment seeks to strengthen the traditional liberal arts education provided at Dartmouth, in an age when individuals can be liberally and professionally educated only if they have the capacity to weigh issues and problems in their global, as opposed to their national or parochial, context. The level of understanding we hope to achieve begins with a competence in another language but much more, it includes a commitment to appreciate the history and culture of other's, to accept diversity, and to promote a process, within traditional disciplines, of testing ideas.

The hallmark of the enterprise will be the variety and pervasiveness of activity throughout the College, rather than the visibility of a single program set off by itself The Endowment will support a number of activities some of which, while already ongoing, must be sustained with additional resources; others will be new initiatives in the College. Some examples:

o Faculty development and research in the study offoreign cultures and societies and international relationships, especially those relating to world conflict andcooperation.

o The expansion of the international content of undergraduate courses and the development in the Graduateand Professional -Schools of programs that focus on international issues such as technology transfers, including thesharing of traditional technologies; international flows ofresources, goods, and credit; and development and management of health systems.

o The consolidation and enrichment of languageinstruction and foreign study programs, including theirextension beyond the North American and Europeancenters in which they have heretofore operated. The newEnvironmental Studies program in Kenya and theChinese language program in Beijing are examples ofthis expansion.

o The organization of campus-wide programs centeredon foreign societies and cultures and on pressing international issues, in cooperation with major campus centerssuch as Hopkins, Hood, Rockefeller, Fairchild, and theTucker Foundation as well as with the Graduate andProfessional Schools. o Student-initiated activities and internship opportunities for undergraduates in the United Nations, ininternational organizations, and in positions abroad.

These activities can be directed at, and will make possible, numerous programs, ranging from the study of United States relations with countries in this hemisphere, to studies of the theories and processes of international cooperation, and to the study of the contributions of literature, music and art to nationalism and to internationalism.

The projected programs will change and evolve, but collectively they will expand the context of all education that takes place at Dartmouth. Our purpose cannot be contained in but a single structure or program, for just as no single course can provide a liberal arts education, no single strategy can achieve our goal of bringing all students to a sophisticated level of appreciation of the world community. We seek to create an attitude of mind sustained by many kinds of activity. Only a diversity of strategies, all directed toward a common goal, will shape perspectives and create that attitude.

Dudley W. Orr Attorney,Trustee of the College 1941-1971Doctor of Laws 1972

Joseph Losey Filmmaker, Winner of the Palme War1971 Cannes Film Festival,Doctor of Humane Letters 1973

Maurice Mandelbaum Professor Emeritus of Philosophy,The Johns Hopkins University,Doctor of Humane Letters 1979

F. William Andres Attorney,Trustee of the College 1963-1977Doctor of Laws 1979

Foreign Study Program, China

John Dickey: Classmate, President, Friend.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

December 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhere They Hang Their Hats

December 1982 By Steve Farnsworth and Jean Korelitz -

Feature

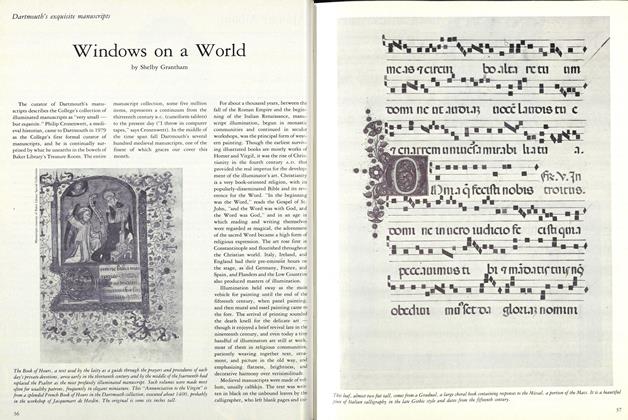

FeatureWindows on a World

December 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the World

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleRound the Girdled Earth...

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleOff to a Good Start.

December 1982 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47

Article

-

Article

ArticleGENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANY FELLOWSHIPS IN SCIENCE

April, 1923 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Totals Comparisons for 1943 and 1944

May 1945 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1960 -

Article

ArticleFace to Watch

Mar/Apr 2001 -

Article

ArticleSquash

JANUARY 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleCLASS OF 1901

June 1916 By Walter S. Young