PHILOSOPHY IN MEDICINE: CONCEPTUAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES IN MEDICINE AND PSYCHIATRY by Charles M. Culver and Bernard Gert Oxford University Press, 1982 . 201 pp.$18.95

A few decades ago, medical ethics and philosophy were given no formal place in the curricula of most United States medical schools. They were "enrichment" subjects at best part of the cultural extracurricular activity of the medical school or teaching hospital. They were good topics for honorary society agendas, sponsored symposia, commencement addresses, and inter-faith seminars. Today, ethical issues in medicine are a high priority subject for formal curricular attention. In our medical schools, sections, divisions, and even departments have grown steadily wherein faculties are being organized to investigate, teach, and consult on ethical problems that beset modern medical practice.

The humanistic problems of health care become ever more complicated and compelling as the power of medical science and technology becomes more awesome and as health care delivery becomes more specialized and fragmented. Uncertainty, and even mistrust, undermine public confidence in a system of health care wherein it is difficult to fix responsibility for the protection of patients' rights and autonomy. Judicial and even legislative bodies rush to fill perceived or real voids in such areas. Medical journals print numerous articles that address ethical and philosophical issues, articles that in the past rarely commanded prime space in these periodicals. And now, useful and practical handbooks, monographs, and texts are becoming available for ready reference in medical case discussions.

One of the newest and best of such handbooks combines the scholarship, experience, and research of a Dartmouth psychiatrist and a Dartmouth philosopher, who have found collaboration within the institution natural and rewarding. Their brief but incisive text deals with several of the most important and cogent ethical issues of current medical practice. Their approach is to clarify and sharpen our understanding of words and concepts used frequently in medical discussions of ethical issues. They tackle such complex topics as rationality and irrationality, informed ("valid") consent and mental competence, mental and physical maladies (not simply diseases or disabilities), paternalism and patient autonomy, involuntary hospitalization, and, finally, the definition (criterion) of death.

Culver and Gert employ the method of academic philosophy dispassionate and painstakingly logical dissection of the rational basis for ethical decisions. They seek the relative goods and evils inherent in the moral decisions that physicians are required to make in medical practice. "We believe that what is best for patients has the best chance of emerging when both sides to this (ethical) dispute argue their cases in the clearest possible fashion." And, indeed, their presentation and commentary provide a lucid (and dispassionate) picture of the rational aspects of the issues.

In fact, so rationally are cases illustrated that it is sometimes difficult to recognize them as the kind of living and breathing problems thiat make medical decisions so knotty for physicians. I think that is because ethical issues at the bedside are so steeped in passion. Moral decisions require courage and consume energy. The ordering of moral priorities involves value judgements that are hardly ever the same for two individuals. Commitment to certain values makes their ordering far from dispassionate. Emotional and aesthetic preferences color the issues and make some decisions noble and lovable in the eyes of some and hateful and ugly in the eyes of others (consider abortion or euthenasia, for example).

The virtue of such philosophical analysis is to defuse and to clarify these hotly debated issues, and Culver and Gert do just that. They are very logical and patient in attempting to help us arrive at "morally correct" answers to ethical dilemmas. One has to be satisfied with light rather than warmth in following their quest for a purely rational basis for moral medical decisions, but the reader's efforts are well recompensed. Philosophy has indeed arrived as a discipline of medical practice, education, and research, and this book provides us with a useful text with which to prime ourselves with knowledge and understanding in order to face the morass of moral dilemmas that we confront in modern medical practice.

Gene Stollerman is professor of medicine at theBoston University School of Medicine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

December 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhere They Hang Their Hats

December 1982 By Steve Farnsworth and Jean Korelitz -

Feature

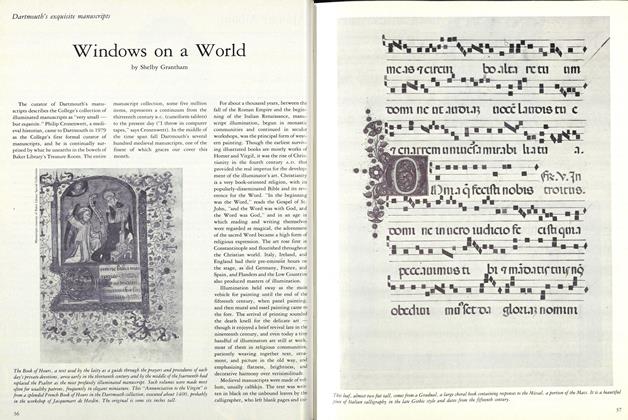

FeatureWindows on a World

December 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the World

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleRound the Girdled Earth...

December 1982 -

Article

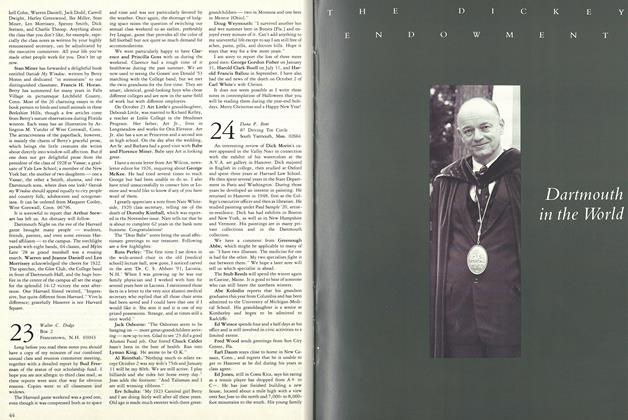

ArticleTHE DICKEY ENDOWMENT

December 1982

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

OCTOBER 1969 -

Books

BooksIT WAS FUN WHILE IT LASTED.

July 1960 By C.E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Books

BooksCELEBRITIES AT OUR HEARTHSIDE.

June 1960 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksLINE OF DEPARTURE,

February 1948 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Books

BooksSOME FACES IN THE CROWD.

June 1953 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksWORKSHOPS FOR THE WORLD.

February 1955 By JOHN G. GAZLEY