Three for Tea

THIS is being written at the mid-point of my stay in London, and I realize that if I have anywhere near as many interesting experiences in the second half of my visit as I had in the first I will have enjoyed one of the richest experiences of my life. As I look back over the first ten weeks, I know that one of the early pleasures suggesting that I was in for a good time was a couple of hours spent with three young members of the Dartmouth community, all of them studying here. Their whole demeanor told me that this great city has not lost its magic for the young visitor, and that realization helped me resolve not to waste my opportunity to enjoy it to the full, as they were doing, regardless of generation gaps.

I had asked the three - two women, recent graduates, and one man, a current student on a foreign study program at the London School of Economics - if they would come to my flat for tea and biscuits one Sunday afternoon and talk to me about their impressions of life here.

The two women are involved in very different kinds of work: One of them is at the beginning of a Ph.D. program in the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London; the other is in the second of four years she will spend at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (known around the world as LAMDA) as a preliminary, if all goes well, to a life in the professional theater. I'm pretty sure that they led quite different kinds of lives at Dartmouth, but with uncommon style they both took on the problems of being a woman at Dartmouth and made major contributions to the life of the place. Neither is likely to forget her alma mater, especially (an old story) the friendships formed there, but how interested they will be in what kinds of alumni contact is anybody's guess. The current student I know because he was one of the most impressive of the freshman advisees I've had over the years - one of those people who doesn't have any trouble linking the word student with the word study. The possessor of a lively mind and a lively interest in the world around him, he was spending a term at L.S.E. with that benevolent old shepherd, Professor Charles McLane '41.

All of them, I found, had become very conscious of their American-ness, and had had it strongly borne in upon them that they are from a country seen as dominating the world in which Britain is somehow having to find its difficult way. They had become much more aware than they had been back home that America (which basically means the Reagan Administration) cannot make a move politically or economically that is not likely to have major repercussions for these millions of people thousands of miles away from Washington, people who feel even more helpless than the average American to influence policies deeply affecting them. One of my guests had been told quite explicitly, "Everyone whose life is shaped by the President's actions ought to be able to vote in the American elections." (As an old-timer, I suggested that if that had been possible over the years there would almost certainly have been President Adlai Stevenson in our history books.) I believe I sense some of the unease that the conquerors have always felt when visiting the colonies; it used to be called, so self-righteously, the white man's burden.

All of them had been made to feel the weight of stereotypical views of America. One was becoming exasperated by the frequency with which she found, in exercises for learning a new language, sentences like "The American doctor is rich. The Amenrican writer is rich." (!) Another had been involved in a heated argument that came to a climax with a British student's shout of "You Americans just don't know what poverty is." And all had faced the amusement of British friends over the title of the film Ordinary People, with their ordinary mansion and their ordinary Mercedes.

We talked about the differences between the typical American university student and the British counterpart, and particularly the obvious "breadth versus depth" issue. Nobody was complacent about it, but none of them had any doubt about their preference for the American approach, having been surprised by finding very bright students of, for example, political science who had not read - let alone studied - a novel in years, and weren't at all concerned about the fact. But there was obvious respect for the basic "keep your eye on the ball" attitude of the British student while on the job, not wasting time with questions asked before any thought had been given to them, not trying to impress ("peacocking" I was interested to discover is what it's called back in Hanover) by simply talking when they had nothing to say. They were all very well aware of what a tiny fraction of the British adolescent population ever gets to go to college or university; and they were all impressed by how the British students do not waste the opportunity once they get it, accepting the responsibility for getting information for themselves (so that the hours with members of the faculty may go to the consideration of the facts rather than to the dissemination of them) and for defining for themselves what they're going to make of their time at university in the broad sense.

We talked about a lot of things, and we kept on talking as we enjoyed a walk together on Hampstead Heath as dusk came on and the lights of the City of London and the West End began to glow in the distance in the - they were very conscious of it - smoggy air. Having some grass underfoot again seems to mean a lot to Dartmouth people.

I asked each of them to tell me what had impressed most or brought most pleasure. For Beth Baron '80, it was the international crucible she found herself in at the School of Oriental and African Studies, an incredibly, perhaps uniquely, rich mix. For Michael Bush '83, the design of the taxicabs I can't afford to take, the pulse of this city s life, and "realizing you're American." For Josefina Bosch '79, the great pleasure to be derived from the infinitude of small details of London's places and people. For all of them, the pervasive sense of safety in this great metropolis meant a great deal, was indeed one of the distinctive features of their experience. An experience they were obviously enjoying deeph, these not-at-all-ordinary people.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

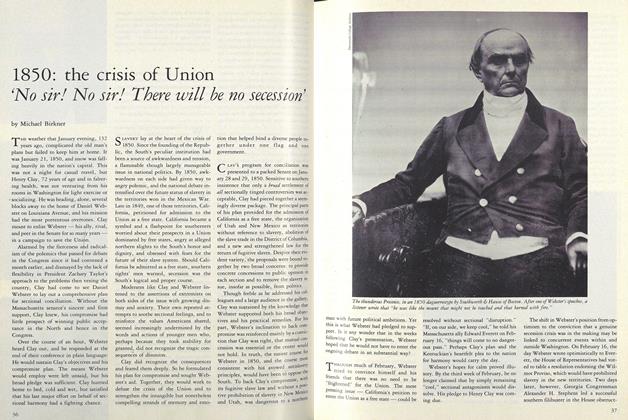

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

March 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

March 1982 By George Kennan -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

March 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

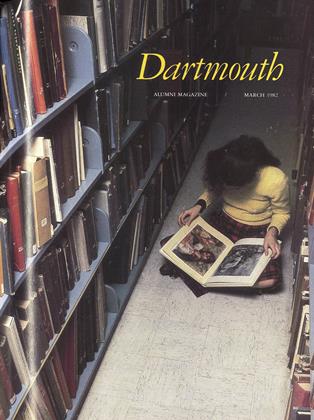

Cover Story

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

March 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Article

ArticleSomeone wrote them, but did anyone read them?

March 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

March 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Peter Smith

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

October 1980 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

APRIL • 1987 -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

MAY 1982 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksAll Biology Is Indebted . . .

November 1983 By Peter Smith -

Books

Books"One Man in His Time..."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksSo Much More

NOVEMBER 1984 By Peter Smith