Not to be left behind in the march of culture, we dug out bathing suit, snorkel, and mask in January and slogged through the snow to Michel Redolfi's "Sonic Waters" concert. It was held in the swimming pool.

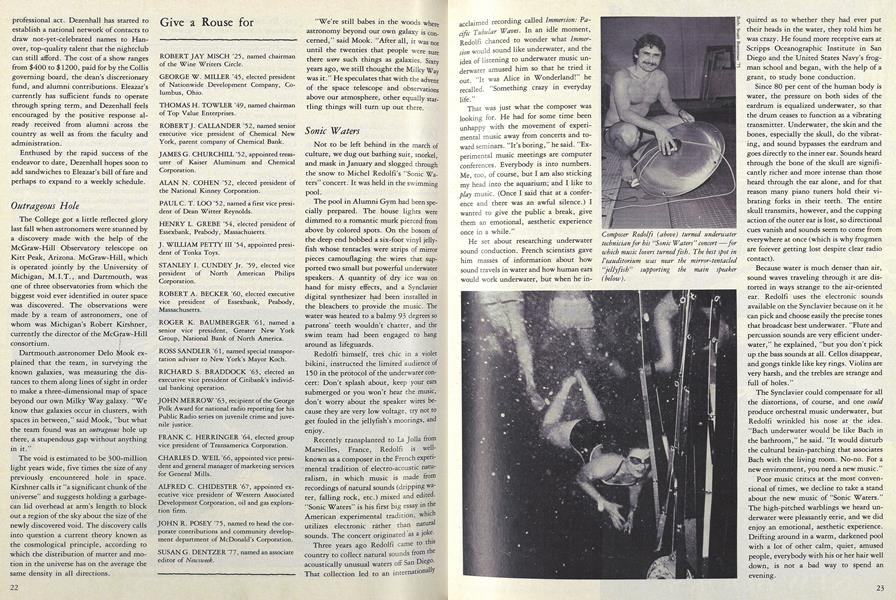

The pool in Alumni Gym had been specially prepared. The house lights were dimmed to a romantic murk pierced from above by colored spots. On the bosom of the deep end bobbed a six-foot vinyl jellyfish whose tentacles were strips of mirror pieces camouflaging the wires that supported two small but powerful underwater speakers. A quantity of dry ice was on hand for misty effects, and a Synclavier digital synthesizer had been installed in the bleachers to provide the music. The water was heated to a balmy 93 degrees so patrons' teeth wouldn't chatter, and the swim team had been engaged to hang around as lifeguards.

Redolfi himself, tres chic in a violet bikini, instructed the limited audience of 150 in the protocol of the underwater concert: Don't splash about, keep your ears submerged or you won't hear the music, don't worry about the speaker wires because they are very low voltage, try not to get fouled in the jellyfish's moorings, and enjoy.

Recently transplanted to La Jolla from Marseilles, France, Redolfi is wellknown as a composer in the French experimental tradition of electro-acoustic naturalism, in which music is made from recordings of natural sounds (dripping water, falling rock, etc.) mixed and edited. "Sonic Waters" is his first big essay in the American experimental tradition, which utilizes electronic rather than natural sounds. The concert originated as a joke.

Three years ago Redolfi came to this country to collect natural sounds from the acoustically unusual waters off San Diego. That collection led to an internationally acclaimed recording called Immersion: Pacific Tubular Waves. In an idle moment, Redolfi chanced to wonder what Immersion would sound like underwater, and the idea of listening to underwater music underwater amused him so that he tried it out. "It was Alice in Wonderland!" he recalled. "Something crazy in everyday life."

That was just what the composer was looking for. He had for some time been unhappy with the movement of experimental music away from concerts and toward seminars. "It's boring," he said. "Experimental

music meetings are computer conferences. Everybody is into numbers. Me, too, of course, but I am also sticking my head into the aquarium; and I like to play music. (Once I said that at a conference and there was an awful silence.) I wanted to give the public a break, give them an emotional, aesthetic experience once in a while."

He set about researching underwater sound conduction. French scientists gave him masses of information about how sound travels in water and how human ears would work underwater, but when he in-quired as to whether they had ever put their heads in the water, they told him he was crazy. He found more receptive ears at Scripps Oceanographic Institute in San Diego and the United States Navy's frogman school and began, with the help of a grant, to study bone conduction.

Since 80 per cent of the human body is water, the pressure on both sides of the eardrum is equalized underwater, so that the drum ceases to function as a vibrating transmitter. Underwater, the skin and the bones, especially the skull, do the vibrating, and sound bypasses the eardrum and goes directly to the inner ear. Sounds heard through the bone of the skull are significantly richer and more intense than those heard through the ear alone, and for that reason many piano tuners hold their vibrating forks in their teeth. The entire skull transmits, however, and the cupping action of the outer ear is lost, so directional cues vanish and sounds seem to come from everywhere at once (which is why frogmen are forever getting lost despite clear radio contact).

Because water is much denser than air, sound waves traveling through it are distorted in ways strange to the air-oriented ear. Redolfi uses the electronic sounds available on the Synclavier because on it he can pick and choose easily the precise tones that broadcast best underwater. "Flute and percussion sounds are very efficient underwater," he explained, "but you don't pick up the bass sounds at all. Cellos disappear, and gongs tinkle like key rings. Violins are very harsh, and the trebles are strange and full of holes."

The Synclavier could compensate for all the distortions, of course, and one could produce orchestral music underwater, but Redolfi wrinkled his nose at the idea. "Bach underwater would be like Bach in the bathroom," he said. "It would disturb the cultural brain-patching that associates Bach with the living room. No-no. For a new environment, you need a new music."

Poor music critics at the most conventional of times, we decline to take a stand about the new music of "Sonic Waters." The high-pitched warblings we heard underwater were pleasantly eerie, and we did enjoy an emotional, aesthetic experience. Drifting around in a warm, darkened pool with a lot of other calm, quiet, amused people, everybody with his or her hair well down, is not a bad way to spend an evening.

Composer Redolfi (above) turned underwatertechnician for his "Sonic Waters" concert —forwhich music lovers turned fish. The best spot in l'eauditorium was near the mirror-tentacled"jellyfish" supporting the main speaker(below).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

March 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

March 1982 By George Kennan -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

March 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

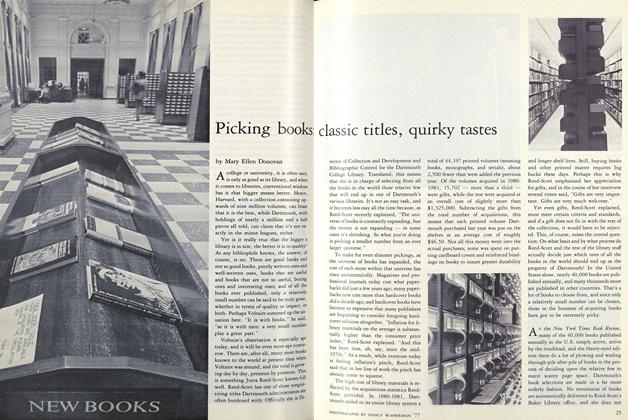

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

March 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Article

ArticleSomeone wrote them, but did anyone read them?

March 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

March 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Article

-

Article

ArticleATHLETIC CARNIVAL

March 1920 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

April 1940 -

Article

ArticleTop Construction Award for John Fondahl '47

March 1976 -

Article

ArticleIs this Dartmouth's Best Quarterback Ever?

October 1993 -

Article

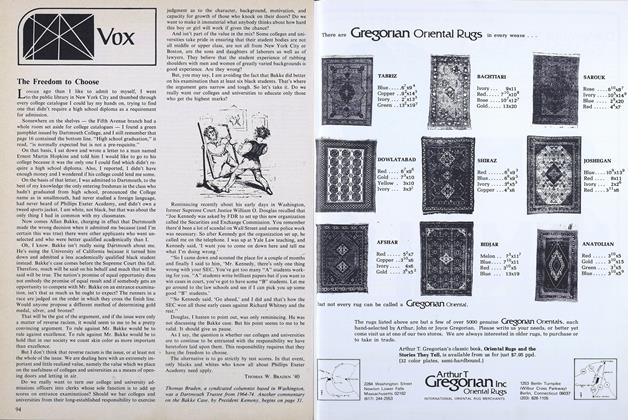

ArticleThe Freedom to Choose

OCT. 1977 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40 -

Article

ArticleTHE INTERCOLLEGIATE INTELLIGENCE BUREAU IN 1918

February 1918 By William McClellan