BLAMING TECHNOLOGY: The Irrational Search for Scapegoats by Samuel C. Florman '46 St. Martin's Press, 1981. 207 pp. $12.95

In Blaming Technology Samuel Florman aims "to bring common sense to bear upon some of the issues that, loosely connected, constitute the public debate about technology," to help counter the "irrationality" of the "antitechnological mood" he finds pervasive in much of America society. Although this is a decidedly ambitious endeavor, ultimately nothing less than the encouragement of a "more realistic appraisal of the human prospect," his book achieves a marked level of success.

The problem, as Florman sees it, arises from the easy propensity of certain intellectuals and popularizers to attribute the dangers and disasters of modern life to "technology" and "technologists." In his opening sections he quickly documents this scapegoating and counterattacks by arguing that the now-popular image of a "technocracy" and a "technological elite" is a "fantasy" and an expression of fear, like a fairy tale about ogres. " Blaming Technology demonstrates that technologists themselves are not centers of power, that technological innovation is a fragile and risky activity, and that when technologists and their systems succeed they do so in response to clearly expressed public needs.

The demonstration is somewhat choppily accomplished by a series of separate chapters on specific subjects. These provide information of a value both independent and supportive of the book's binding thesis. what became of the rotary engine and other touted technological break throughs? Who exactly directs the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers? How did we fail to solve the problem of nuclear waste and what can we do about it now? How do technical standards of quality and quantity come to be set? This book tells us, and

such knowledge leads not to discouragement but to an appreciation of the richness and depth of our social organization. It is an affirmative knowledge, knowledge of how things work. It helped me personally to see why people whose orientation is primarily technological (engineers, for example) tend to be more explicitly cheerful about our political and social systems than those who see themselves as somehow separated from them. Engineers like Florman tend to be optimistic not because they are the sinister or the co-opted "louts" of antitechnologist fantasy, but because they are in the business of making things that work.

But then I never thought they were louts, and this brings me to my one serious criticism of Florman's writing. He likes labels and he seems willing to use them in ways that undercut his own aims. He repeatedly refers with condescension to "academe," described as a place "where jovial professors carry theories under their tweeds like stilettos." He is surprised to find "academic handwringing" treated as "important news" in the public press. He imagines that interdisciplinary studies are "traditionally scorned in departmentalized academe." "Intellectuals" and especially "humanists" come in for more specific derogation. He claims, but does not demonstrate, that the antitechnological fantasy is largely the offspring of "disgruntled humanists." His idea of a representative humanist seems to be Joseph Wood Krutch (surely an anachronism now) or even Theodore Roszak (no thanks). Florman tells us that "because scientists are taught to eliminate personal bias from their frame of reference, the humanist assumes that such people have no access to important 'truths.' " I don't know any humanists who think that. I am a humanist, and I was taught to pay strict attention to the effect of personal bias on my frame of reference. And "feminists" receive a less continuous but regrettably similar treatment in a chapter with the flashy but misleading title, "The Feminist Face of Antitechnology." Such gestures are not merely rhetorical. They undermine the common ground of "communication between people of differing intellectual dispositions" that Florman himself is doing so much to establish.

But the final chapters shake loose from bias and present an admirable, even ennobling view of the proper role of technology in our society. Here Florman combines technological insight and humanistic value to achieve a vision of social responsibility that bridges the cultural gaps. And the high aspirations and standards he sets for his own profession may serve very well as a model for others.

A Victorian specialist, Professor of EnglishThomas Vargish has written and lectured at theDartmouth Institute on the subject of humanismand technology.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHotsy Totsy

April 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Green

April 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

April 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

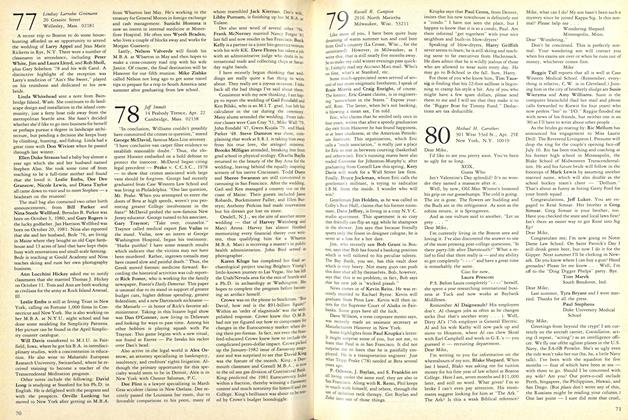

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

April 1982 By Peter Heller -

Article

ArticleCONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1982 -

Article

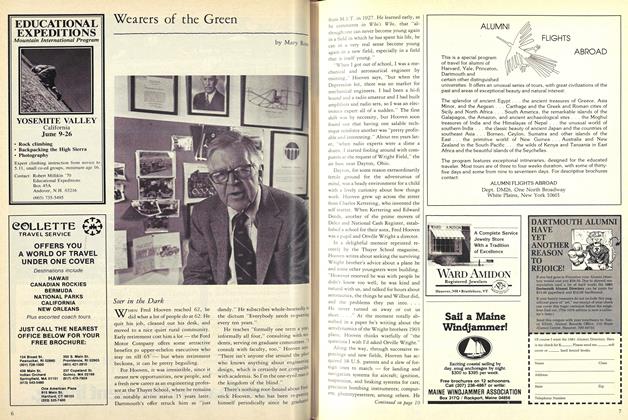

ArticleSeer in the Dark

April 1982 By Mary Ross

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

March 1934 -

Books

BooksDown on the Farm

Jan/Feb 1981 By David M. Shribman'76 -

Books

BooksBRITISH POLICY AND THE TURKISH REFORM MOVEMENT

May 1943 By E. B. Watson '02 -

Books

BooksTHE PHENOMENOLOGY OF MORAL EXPERIENCE.

July 1955 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45 -

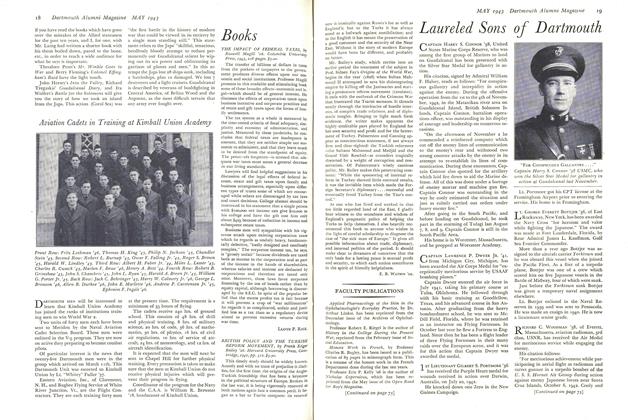

Books

BooksDANIEL WEBSTER

January, 1931 By Leon B. Richardson -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

January, 1925 By Thomas G. Brown