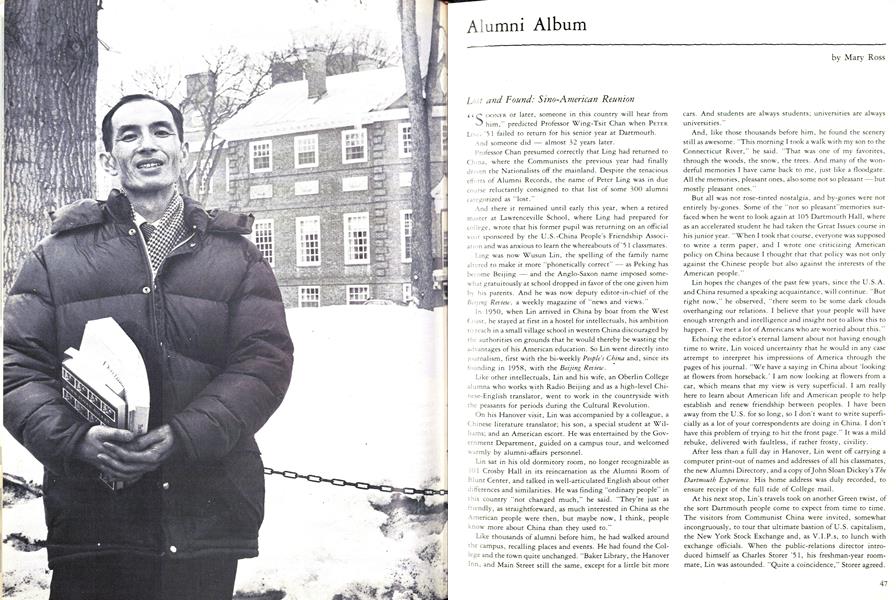

"Sooner or later, someone in this country will hear from him," predicted Professor Wing-Tsit Chan when Peter

Ling '51 failed to return for his senior year at Dartmouth.

And someone did almost 32 years later. Professor Chan presumed correctly that Ling had returned to China, where the Communists the previous year had finally driven the Nationalists off the mainland. Despite the tenacious efforts of Alumni Records, the name of Peter Ling was in due course reluctantly consigned to that list of some 300 alumni categorized as "lost."

And there it remained until early this year, when a retired master at Lawrenceville School, where Ling had prepared for college, wrote that his former pupil was returning on an official visit sponsored by the U.S.-China People's Friendship Association and was anxious to learn the whereabouts of's 1 classmates.

Ling was now Wusun Lin, the spelling of the family name altered to make it more "phonetically correct" as Peking has become Beijing and the Anglo-Saxon name imposed somewhat gratuitously at school dropped in favor of the one given him bY his parents. And he was now deputy editor-in-chief of the Beijing Review, a weekly magazine of "news and views."

In 1950, when Lin arrived in China by boat from the West Coast, he stayed at first in a hostel for intellectuals, his ambition to teach in a small village school in western China discouraged by the authorities on grounds that he would thereby be wasting the advantages of his American education. So Lin went directly into journalism, first with the bi-weekly People's China and, since its founding in 1958, with the Beijing Review.

Like other intellectuals, Lin and his wife, an Oberlin College alumna who works with Radio Beijing and as a high-level Chinese-English translator, went to work in the countryside with the peasants for periods during the Cultural Revolution.

On his Hanover visit, Lin was accompanied by a colleague, a Chinese literature translator; his son, a special student at Williams; and an American escort. He was entertained by the Government Department, guided on a campus tour, and welcomed warmly by alumni-affairs personnel.

Lin sat in his old dormitory room, no longer recognizable as 101 Crosby Hall in its reincarnation as the Alumni Room of Blunt Center, and talked in well-articulated English about other differences and similarities. He was finding "ordinary people" in this country "not changed much," he said. "They're just as friendly, as straightforward, as much interested in China as the American people were then, but maybe now, I think, people know more about China than they used to."

Like thousands of alumni before him, he had walked around the campus, recalling places and events. He had found the College and the town quite unchanged. "Baker Library, the Hanover Inn, and Main Street still the same, except for a little bit more cars. And students are always students; universities are always universities."

And, like those thousands before him, he found the scenery still as awesome. "This morning I took a walk with my son to the Connecticut River," he said. "That was one of my favorites, through the woods, the snow, the trees. And many of the wonderful memories I have came back to me, just like a floodgate. All the memories, pleasant ones, also some not so pleasant but mostly pleasant ones."

But all was not rose-tinted nostalgia, and by-gones were not entirely by-gones. Some of the "not so pleasant"memories surfaced when he went to look again at 105 Dartmouth Hall, where as an accelerated student he had taken the Great Issues course in his junior year. "When I took that course, everyone was supposed to write a term paper, and I wrote one criticizing American policy on China because 1 thought that that policy was not only against the Chinese people but also against the interests of the American people."

Lin hopes the changes of the past few years, since the U.S.A. and China resumed a speaking acquaintance, will continue. "But right now," he observed, "there seem to be some dark clouds overhanging our relations. I believe that your people will have enough strength and intelligence and insight not to allow this to happen. I've met a lot of Americans who are worried about this."

Echoing the editor's eternal lament about not having enough time to write, Lin voiced uncertainty that he would in any case attempt to interpret his impressions of America through the pages of his journal. "We have a saying in China about 'looking at flowers from horseback.' I am now looking at flowers from a car, which means that my view is very superficial. I am really here to learn about American life and American people to help establish and renew friendship between peoples. I have been away from the U.S. for so long, so I don't want to write superficially as a lot of your correspondents are doing in China. I don't have this problem of trying to hit the front page." It was a mild rebuke, delivered with faultless, if rather frosty, civility.

After less than a full day in Hanover, Lin went off carrying a computer print-out of names and addresses of all his classmates, the new Alumni Directory, and a copy of John Sloan Dickey's TheDartmouth Experience. His home address was duly recorded, to ensure receipt of the full tide of College mail.

At his next stop, Lin's travels took on another Green twist, of the sort Dartmouth people come to expect from time to time. The visitors from Communist China were invited, somewhat incongruously, to tour that ultimate bastion of U.S. capitalism, the New York Stock Exchange and, as V.I.P.s, to lunch with exchange officials. When the public-relations director introduced himself as Charles Storer '5l, his freshman-year roommate, Lin was astounded. "Quite a coincidence," Storer agreed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lovinses and the Soft-Energy Path

June 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureMAIN STREET

June 1982 By Nancy Wasserman -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWarming up for 50 years: The yeast of elderly innocence

June 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

June 1982 By Adrian A. Walser -

Sports

SportsBig Enough

June 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

June 1982 By Francis R. Drury Jr.

Mary Ross

-

Feature

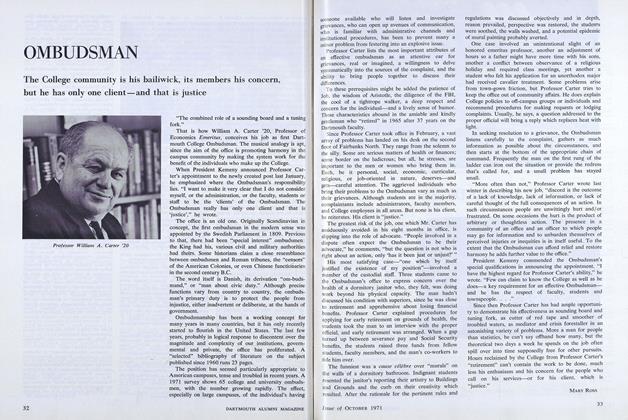

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

OCTOBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

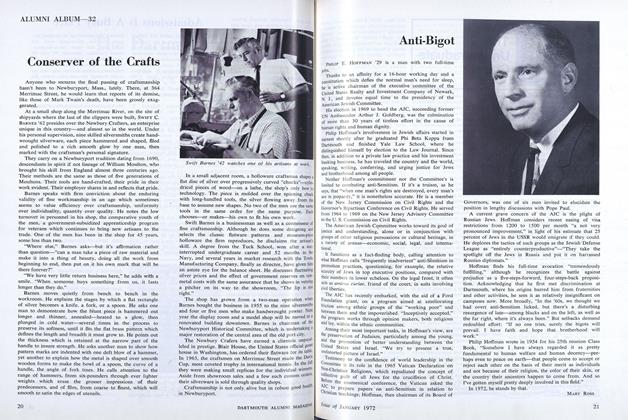

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

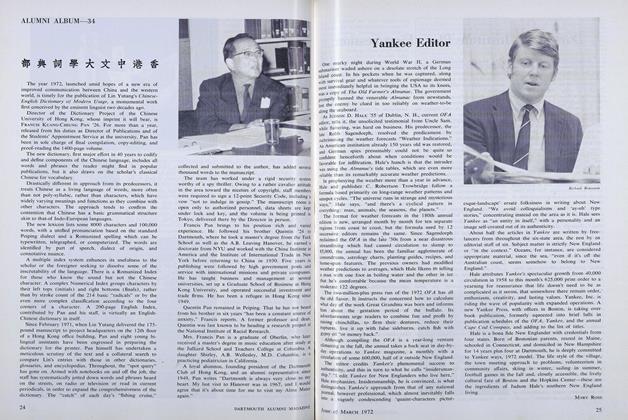

ArticleYankee Editor

MARCH 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

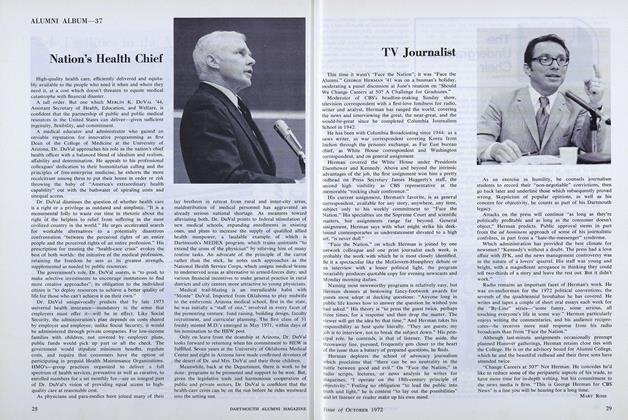

ArticleTV Journalist

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

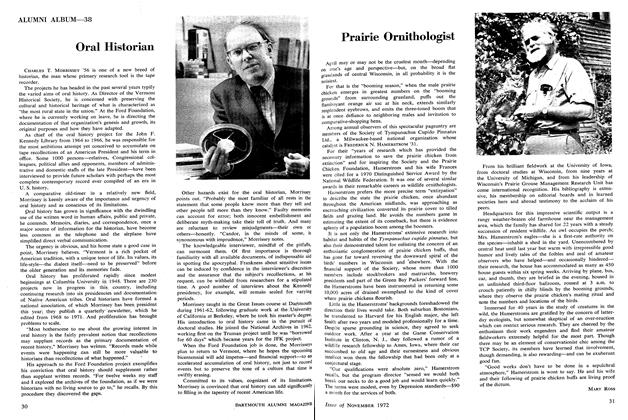

ArticlePrairie Ornithologist

NOVEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

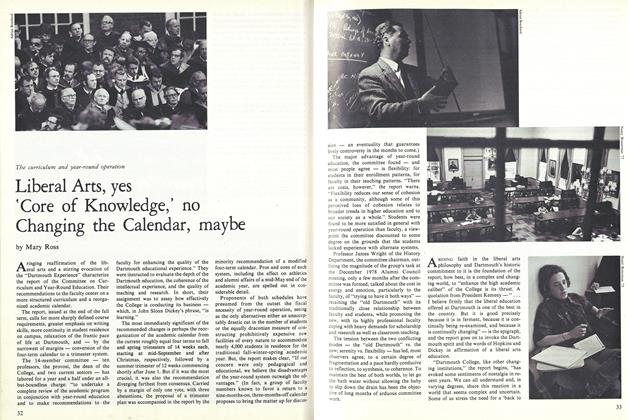

FeatureLiberal Arts, yes 'Core of Knowledge,' no Changing the Calendar, maybe

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Mary Ross

Article

-

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleSOMETHING ABOUT BUSINESS

June, 1926 -

Article

ArticleNew Faculty Leaves

February 1943 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

January 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleThayer School

December 1945 By John H. Minchich '29. -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1876 FIFTY YEARS AFTER

June, 1926 By Samuel Merrill '76