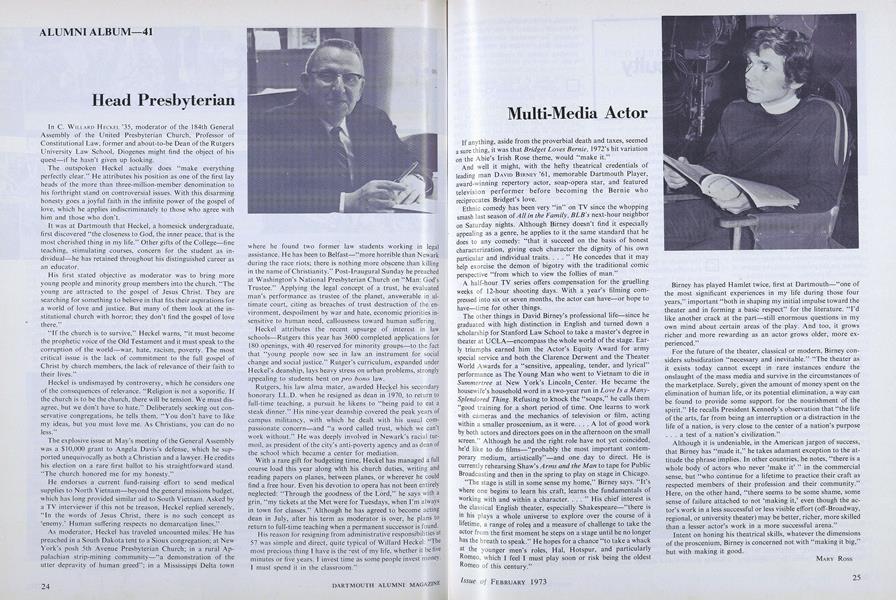

If anything, aside from the proverbial death and taxes, seemed a sure thing, it was that Bridget Loves Bernie, 1972's hit variation on the Abie's Irish Rose theme, would "make it."

And well it might, with the hefty theatrical credentials of leading man DAVID BIRNEY '61, memorable Dartmouth Player, award-winning repertory actor, soap-opera star, and featured television performer before becoming the Bernie who reciprocates Bridget's love.

Ethnic comedy has been very "in" on TV since the whopping smash last season of All in the Family, BLB's next-hour neighbor on Saturday nights. Although Birney doesn't find it especially appealing as a genre, he applies to it the same standard that he does to any comedy: "that it succeed on the basis of honest characterization, giving each character the dignity of his own particular and individual traits...." He concedes that it may help exorcise the demon of bigotry with the traditional comic perspective "from which to view the follies of man."

A half-hour TV series offers compensation for the gruelling weeks of 12-hour shooting days. With a year's filming compressed into six or seven months, the actor can have—or hope to have—time for other things.

The other things in David Birney's professional life—since he graduated with high distinction in English and turned down a scholarship for Stanford Law School to take a master's degree in theater at UCLA—encompass the whole world of the stage. Early special service and both the Clarence Derwent and the Theater World Awards for a "sensitive, appealing, tender, and lyrical" performance as The Young Man who went to Vietnam to die in Summertree at New York's Lincoln Center. He became the housewife's household word in a two-year run in Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. Refusing to knock the "soaps," he calls them "good training for a short period of time. One learns to work with cameras and the mechanics of television or film, acting within a smaller proscenium, as it were.... A lot of good work by both actors and directors goes on in the afternoon on the small screen." Although he and the right role have not yet coincided, he'd like to do films—"probably the most important contemporary medium, artistically"—and one day to direct. He is currently rehearsing Shaw's Arms and the Man to tape for Public Broadcasting and then in the spring to play on stage in Chicago.

"The stage is still in some sense my home," Birney says. "It's where one begins to learn his craft, learns the fundamentals of working with and within a character...." His chief interest is the classical English theater, especially Shakespeare—"there is in his plays a whole universe to explore over the course of a lifetime, a range of roles and a measure of challenge to take the actor from the first moment he steps on a stage until he no longer has the breath to speak." He hopes for a chance "to take a whack at the younger men's roles, Hal, Hotspur, and particularly Romeo, which I feel I must play soon or risk being the oldest Romeo of this century."

Birney has played Hamlet twice, first at Dartmouth—"one of the most significant experiences in my life during those four years," important "both in shaping my initial impulse toward the theater and in forming a basic respect" for the literature. "I'd like another crack at the part—still enormous questions in my own mind about certain areas of the play. And too, it grows richer and more rewarding as an actor grows older, more experienced."

For the future of the theater, classical or modern, Birney considers subsidization "necessary and inevitable." "The theater as it exists today cannot except in rare instances endure the onslaught of the mass media and survive in the circumstances of the marketplace. Surely, given the amount of money spent on the elimination of human life, or its potential elimination, a way can be found to provide some support for the nourishment of the spirit." He recalls President Kennedy's observation that "the life of the arts, far from being an interruption or abstraction in the life of a nation, is very close to the center of a nation's purpose ... a test of a nation's civilization."

Although it is undeniable, in the American jargon of success, that Birney has "made it," he takes adamant exception to the attitude the phrase implies. In other countries, he notes, "there is a whole body of actors who never 'make it' " in the commercial sense, but "who continue for a lifetime to practice their craft as respected members of their profession and their community." Here, on the other hand, "there seems to be some shame, some sense of failure attached to not 'making it,' even though the actor's work in a less successful or less visible effort (off-Broadway, regional, or university theater) may be better, richer, more skilled than a lesser actor's work in a more successful arena."

Intent on honing his theatrical skills, whatever the dimensions of the proscenium, Birney is concerned not with "making it big," but with making it good.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Gives Its Name to U.S.—Soviet Understanding

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1973 -

Feature

FeatureThe Making of a Mural

February 1973 By GOBIN STAIR '33 -

Feature

FeatureToujours jeunes pour les voyages

February 1973 By IRA BERMAN '42 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Alumni College

February 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

MARY ROSS

-

Feature

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

OCTOBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

APRIL 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleArts Catalyst

MARCH 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleBiathlete

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

Article"To the conquest of the unknown and the advancement of knowledge."

MARCH 1984 By Mary Ross