April may or may not be the cruelest month—depending on one's age and perspective—but, on the broad flat grasslands of central Wisconsin, in all probability it is the noisiest.

For that is the "booming season," when the male prairie chicken emerges in greatest numbers on the "booming grounds" from surrounding grassland, puffs out the flamboyant orange air sac at his neck, extends similarly resplendent eyebrows, and emits the three-toned boom that is at once defiance to neighboring males and invitation to comparative-shopping hens.

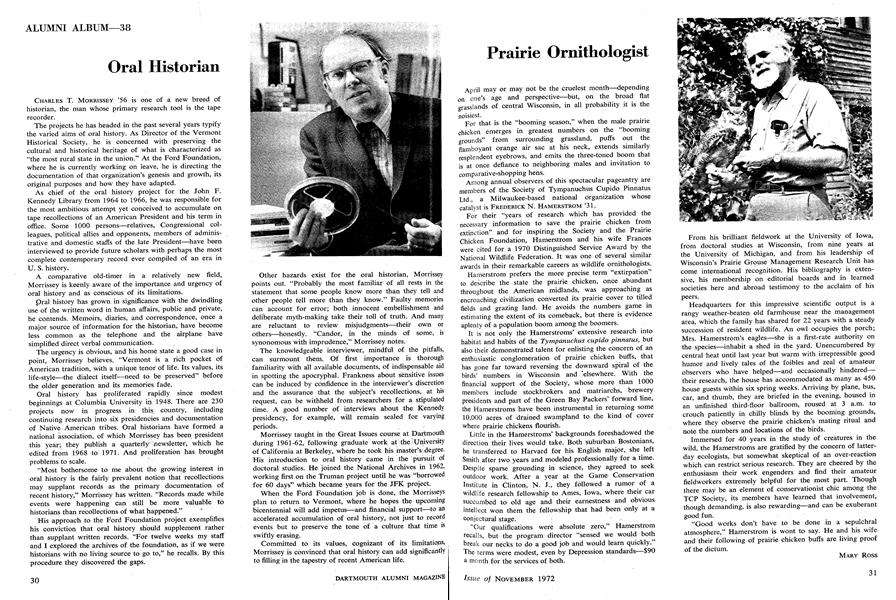

Among annual observers of this spectacular pageantry are members of the Society of Tympanuchus Cupido Pinnatus Ltd., a Milwaukee-based national organization whose catalyst is FREDERICK N. HAMERSTROM '31.

For their "years of research which has provided the necessary information to save the prairie chicken from extinction" and for inspiring the Society and the Prairie Chicken Foundation, Hamerstrom and his wife Frances were cited for a 1970 Distinguished Service Award by the National Wildlife Federation. It was one of several similar awards in their remarkable careers as wildlife ornithologists.

Hamerstrom prefers the more precise term "extirpation" to describe the state the prairie chicken, once abundant throughout the American midlands, was approaching as encroaching civilization converted its prairie cover to tilled fields and grazing land. He avoids the numbers game in estimating the extent of its comeback, but there is evidence aplenty of a population boom among the boomers.

It is not only the Hamerstroms' extensive research into habitat and habits of the Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus, but also their demonstrated talent for enlisting the concern of an enthusiastic conglomeration of prairie chicken buffs, that has gone far toward reversing the downward spiral of the birds' numbers in Wisconsin and elsewhere. With the financial support of the Society, whose more than 1000 members include stockbrokers and matriarchs, brewery presidents and part of the Green Bay Packers forward line, the Hamerstroms have been instrumental in returning some 10,000 acres of drained swampland to the kind of cover where prairie chickens flourish.

Little in the Hamerstroms' backgrounds foreshadowed the direction their lives would take. Both suburban Bostonians, he transferred to Harvard for his English major, she left Smith after two years and modeled professionally for a time. Despite sparse grounding in science, they agreed to seek outdoor work. After a year at the Game Conservation Institute in Clinton, N. J., they followed a rumor of a wildlife research fellowship to Ames, lowa, where their car succumbed to old age and their earnestness and obvious intellect won them the fellowship that had been only at a conjectural stage.

"Our qualifications were absolute zero," Hamerstrom recalls, but the program director "sensed we would both break our necks to do a good job and would learn quickly. The terms were modest, even by Depression standards-$90 a month for the services of both.

From his brilliant fieldwork at the University of lowa, from doctoral studies at Wisconsin, from nine years at the University of Michigan, and from his leadership of Wisconsin's Prairie Grouse Management Research Unit has come international recognition. His bibliography is extensive, his membership on editorial boards and in learned societies here and abroad testimony to the acclaim of his peers.

Headquarters for this impressive scientific output is a rangy weather-beaten old farmhouse near the management area, which the family has shared for 22 years with a steady succession of resident wildlife. An owl occupies the porch, Mrs. Hamerstrom's eagles—she is a first-rate authority on the species—inhabit a shed in the yard. Unencumbered by central heat until last year but warm with irrepressible good humor and lively tales of the foibles and zeal of amateur observers who have helped—and occasionally hindered- their research, the house has accommodated as many as 450 house guests within six spring weeks. Arriving by plane, bus, car, and thumb, they are briefed in the evening, housed in an unfinished third-floor ballroom, roused at 3 a.m. to crouch patiently in chilly blinds by the booming grounds, where they observe the prairie chicken's mating ritual and note the numbers and locations of the birds.

Immersed for 40 years in the study of creatures in the wild, the Hamerstroms are gratified by the concern of latterday ecologists, but somewhat skeptical of an over-reaction which can restrict serious research. They are cheered by the enthusiasm their work engenders and find their amateur fieldworkers extremely helpful for the most part. Though there may be an element of conservationist chic among the TCP Society, its members have learned that involvement, though demanding, is also rewarding—and can be exuberant good fun.

"Good works don't have to be done in a sepulchral atmosphere," Hamerstrom is wont to say. He and his wife and their following of prairie chicken buffs are living proof of the dictum.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFour Views of Educational Opportunity at Convocation Opening the 203rd Year

November 1972 -

Feature

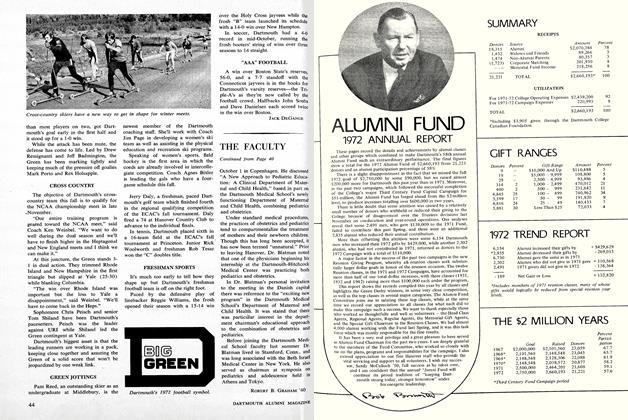

Feature1972 ANNUAL REPORT

November 1972 -

Feature

FeatureElection '72: A Historian's View

November 1972 By JAMES E. WRIGHT -

Feature

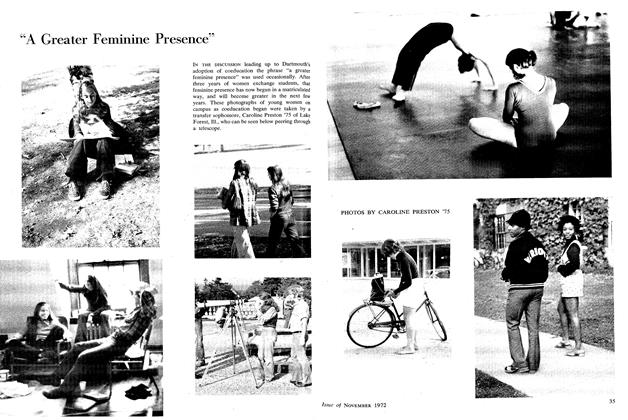

Feature"A Greater Feminine Presence"

November 1972 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1972 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

November 1972

MARY ROSS

-

Feature

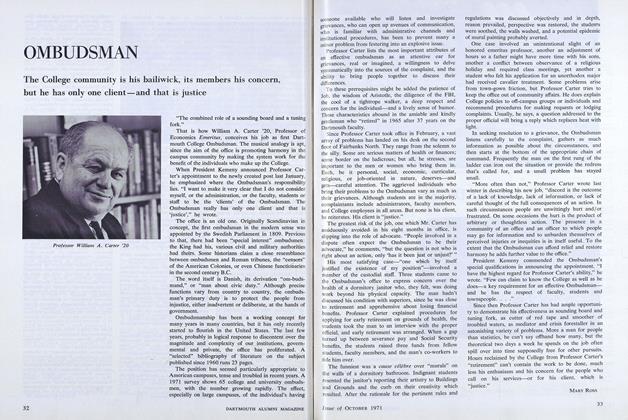

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

OCTOBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleTriple-Threat Academician

DECEMBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

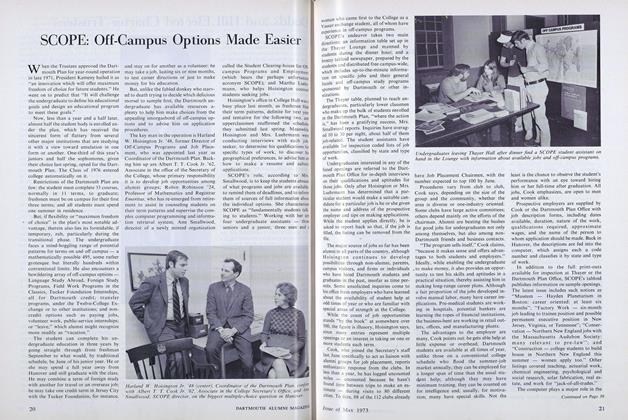

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

MAY 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

Article"To the conquest of the unknown and the advancement of knowledge."

MARCH 1984 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Mary Ross