Personal answers from some Dartmouth persons whose definitions of success have in varying ways been influenced by the College

When I was growing up in Rochester, N.Y., three of my best friends were Eddie, Lawrence, and Jimmy. Although our families knew varying degrees of wealth, all four of us were what you would call privileged. In many ways, our locomotion towards college and professional careers was as predictable as rush-hour traffic. None of us could have told you exactly where he was heading in 1966, but each of us suspected that his destination would be familiar territory. Who would have thought that the tidal wave of the late 60's would wash away all landmarks and signs to point the way?

In the early 70's, we four went our separate ways, each one following a course which bore little resemblance to the clear path that once lay before us. Eddie, whose life had been shattered at. an early age by the murder of his father, ended up in Attica State Prison, busted for dealing dope. Lawrence succumbed to the call of the wild and followed his log-cabin dream to Alaska as a Vista volunteer.'Jimmy, once famed for his low handicap and knack for making money, embraced the counter culture with a passion he once reserved for his nine iron. And I, I took the road less traveled by and ended up in Japan, courtesy of the United States Navy.

This bit of ancient history may sound strange to present-day students. After all, today the old markers have long since been replaced and, once again, the path ahead is now clear. Obstacles introduced by the Vietnam war have long since been swept away along with a bias towards big business. For the enterprising traveler today, "Success" is a destination as easily reached as White River Junction. Or is it?

Certainly the trail which Eddie, Lawrence, and Jimmy followed was bumpy at best. At last report, Eddie emerged as a social worker, although rumor has it that he still expresses interest in an import business. Lawrence, with his second wife and ready-made family, has settled down to a small town law practice. And Jimmy, the darling turned disappointment of the country club set, continues to defy categorization by running a natural foods distributorship. The only solace he provides his parents' friends is that he continues to make money in spite of himself.

Have we four travelers achieved success? After all, none of us is rich and famous, although Eddie achieved a bit of infamy for ending up in Attica. Jimmy is a mover and shaker in the co-op business, but is still generally regarded by the older crowd as never having quite "come around." When people talk about Jimmy, their voices often trail off in a wistful sigh. At best, he is lamented. As for Lawrence, he certainly seems to have found his niche, although he has long since traded in his denims for three-piece suits. I suspect that many of his tools now gather dust on a shelf along with his ambition to forge a cabin out of the wilderness.

How about myself? Have I achieved success? Certainly, if I took a true-false test for success, I would score pretty well. I have a job I enjoy, a family I love and am loved by in return, a super dog, a house with a beautiful view and a manageable mortgage, a new station wagon, and;a respected position in my community. Aim I a success? I honestly don't know. If I subscribe to Tom Landry's definition of a happy life something to hope for, something to do, someone to love I'm in relatively good shape. But success is an elusive concept. It's a lot like chasing a piece of paper across the green on a windy day. Every time success is within your grasp, it seems to slip away. You can hold on to it for a time, but beware of the next gust of wind.

Given the constant battle to strive for success, I think that it is well worth heeding Helen Hayes' advice. She draws a distinction between achievement and success. By her definition, "Achievement is the knowledge that you have studied and worked hard and done the best that is in you. Success is being praised by others and that's nice, too, but not as important or satisfying. Always aim for achievement and forget about success."

While I continue to chase my piece of paper across the green, let me turn to a discussion of what constitutes success for today's Dartmouth graduate.

When I returned to Dartmouth as a career counselor in 1978, my attention was drawn to an editorial entitled "Lawyers and Ditches" which appeared in The D that fall. The author, a member of the class of 1974, shared his concern about class snobbery which he felt placed a higher value on status than substance. He wrote:

"And what of the person who could have been a lawyer but chose to be a ditch digger? Enter the type of snob who sees a person and evaluates him on the basis of how much his job 'contributes' to mankind. But there is a universal scale for measuring good works and one's occupation alone can never be a yardstick of the amount mankind benefits from his life. It is possible that a person with an infectious zest for life, who has strong and lasting friendships, who does whatever he does enthusiastically and well, or who does a good job of raising a family, does mankind better service in the long run than one who is personally responsible for adding 200 pages to the code of federal regulations."

He went on to say: "For a student who views odiously the prospect of digging ditches, a liberal education can have two effects: He can learn enough so that he never has to dig ditches, or he can learn enough to know that there's really nothing wrong with digging ditches."

Needless to say, I was quite impressed by this editorial and immediately began to delve deeper into the Dartmouth definition of success. I didn't have to look hard for evidence of albatrosses all around me. Student after student whom I counseled came in weighted down by a burden of expectations which was frightening to behold. In our counseling sessions, we would talk for awhile about the student's interests or skills, but always there remained an unspoken presence in the room. I sensed that many students regarded my probes into their pleasure centers as satisfying diversions but, in the end, irrelevant. "Don't you see, don't you see?" they all but cried out. "How can we discuss my interest in woodworking or photography? What does that have to do with making a living? I'm a Dartmouth student, don't you see?"

Even if I didn't fully acknowledge what I was seeing or hearing at the time, I soon discovered other signs of distress which I couldn't ignore. During a visit to Philadelphia, I went out for a couple of drinks with an old friend from Dartmouth. The conversation eventually turned to our upcoming 10th reunion, which I naturally assumed my friend would attend. After all, hadn't he been the one to constantly send me reminders to make contributions and stay involved. You can imagine how flabbergasted I was to find out that he didn't plan to attend, not because he was otherwise occupied but because, by his own definition, he hadn't made it yet. How could I even imagine that he would feel comfortable clinking cups with our classmates when he was still struggling to make ends meet as a gypsy scholar, riding the commuting trains to teaching stints at colleges in the Philadelphia area?

Seeing is not believing. To fully appreciate what one student referred to as "the natural progression of things," I had to recall my own days as a Dartmouth undergraduate. I can still remember walking across campus, experiencing the intense pressure of upcoming exams, wondering why life could not be simpler. I often cast envious glances at buildings-and-grounds workers who took great satisfaction in improving the appearance of the Dartmouth campus. Why couldn't I experience that pleasure? Why did I have to pursue a different destiny?

Upon reflection, it occurred to me then and now that Dartmouth students have always labored under an intense burden of expectations. Somehow, the word has been passed from generation to generation that only certain careers are acceptable for recipients of a Dartmouth degree. I find this revelation mystifying because the pantheon of Dartmouth heroes and heroines is packed with people who have made their mark in a variety of pursuits. Ask any student to engage in the all-time favorite collegiate game of oneupsmanship and you will receive a torrent of "did you know's?" Did you know that Dr. Seuss went to Dartmouth? Not to mention Mr. Rogers. Did you know that Grant Tinker is a Dartmouth alum or Senator Paul Tsongas? How about actor David Birney or football stars Nick Lowery and Reggie Williams.' Etc. etc. Hearing the names singled out for adulation, I can't help wondering why we glorify entertainment figures or politicians and, at the same time, act as if they were deviants from the norm. We choose to celebrate the achievements of iconoclasts and yet ignore their examples when charting our own career paths.

I don't envy today's undergraduates. Pressures from home and peers are magnified tenfold by headlines which question the market value of a liberal arts education. Parents pass on their fears that a 512,000 investment shouldn't be wasted on frivolous pursuits; thus, courses which once would have been eagerly embraced are shunned. In the face of this assault, it's no wonder that students feel encumbered, constricted by their upbringing to certain courses of action.

One senior recently drove this point home when he recounted a recent discussion he had with his parents about his future. His parents, naturally concerned about the job market, urged him to accept a high-paying offer from IBM where he had worked for the past six months. The senior, on the other hand, expressed interest in obtaining hands-on experience as a carpenter in preparation for an eventual career in the construction field. Should he reject his parents' counsel and pursue his dream? Or should he be practical and take a position which others would consider a plum, tangible evidence that he wears the Dartmouth green and that's enough.

His conflict reminded me of a cartoon which hangs in our office. It portrays a father leading his son by the hand past a row of professionals holding placards advertising their salaries. Careers at the lower end of the pay scale teacher, fireman, nurse, policeman are passed by quickly as the father urges his son to "move on to the important people." In this sketch, the important people are sports stars, rock stars, and movie stars, with price tags ranging up to $1.5 million.

This tendency to equate excellence with financial reward and prestige is all too common in our society. It leads many Dartmouth students to cast themselves, into careers that are entirely out of whack with their personalities. As I wrote in an editorial which was reprinted in The D this fall, "excellence is not a province inhabited exclusively by practitioners of select professions." As John Gardner, former Cabinet secretary and founder of Common Cause, points out:

In the intellectual field alone there are many kinds of excellence. There is the kind of intellectual activity that leads to a new theory. And the kind that leads to a new machine. There is the mind that finds its most effective expression in teaching and the mind that is most at home in research. There is the mind that works best in quantitative terms and the mind that luxuriates in poetic imagery. And, there is excellence in art, in music, in craftsmanship, in human relations, in technical work, in leadership, in parental responsibilities."

Perhaps the steelworker in Studs Terkel's classic book Working summed up the feelings of all laborers when he declared:

"If a carpenter built a cabin for poets, I think the least the poets owe the carpenter is just three or four one-liners on the wall. A little plaque: 'Though we labor with our minds, this place we can relax in was built by someone who can work with his hands. And his work is as noble as ours.' I think the poet owes something to the guy who builds the cabin for him."

Success, as I have said, is an elusive concept. It is a trendy word, to borrow a description from David Frost. Advice columnists, entertainers, and best-selling authors, not to mention career counselors and coaches, all offer formulas for achieving success. "Never continue in a job you don't enjoy. If you're happy in what you're doing, you'll like yourself, you'll have inner peace. And if you have that, along with physical health, you will have had more success than you could possibly have imagined," advises Johnny Carson.

In the final analysis, there is no universal definition of what constitutes success. It's a very personal experience. No one else can show the way because each of us has to discover his or her own path to success. Most of the people whom I consider to be successful take great pride in their work, but recognize that work cannot be all-consuming. The inner peace which Johnny Carson notes is attained by doing the best one can and taking satisfaction in the results.

I would urge Dartmouth students today to seek success wherever their talents and aspirations lead them. As Ibsen says, "Seek to build castles in the air to find true happiness." Look to the 800 corporate heads who graduated from Dartmouth as role models, but also look to the homemakers and hotel operators, teachers, and social workers. Success surrounds us, if we just open our eyes.

One of my favorite role models is a man who could never open his eyes, Robert Russell, the author of To Catch an Angel. Blinded at an early age by a freak accident, Russell devoted his life to overcoming his handicap. At the end of the book, he emerges as a professor at a liberal arts college, having trained for the task at Hamilton, Yale, and Oxford. Although his accomplishments are certainly impressive, what particularly inspires me about his life is that he constantly challenges himself to rise above complacency and to reject security in favor of stimulation. He refers to the inhabitants of H. G. Wells' The Country of the Blind who think that "the air is alive with singing angels. Because they can always hear, but never see the birds, and because they can never catch one to examine it, they build legends about these phantoms that exist outside their perceivable universe."

We could do worse than to follow Robert Russell's example and try to catch an angel. The pursuit of excellence may be the best barometer of all by which to measure success.

The following views were expressed at a paneldiscussion of success, entitled "We Wear theDartmouth Green. Is That Enough?"

Roderick W. Gilkey

Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry Adjunct Assistant Professor, Tuck School

What is a life of success? I recall an observation made by Soren Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher, who said, "The problem with life is that we understand it backwards, but we have to live it forwards. "Fairly tricky! Here we are at Dartmouth, hopefully getting knowledge. The real question is whether we are also getting wisdom, the kind of wisdom that enables one to live a life one feels good about, while it's happening and when one looks back upon it. As a practicing clinical psychologist, my own sense is that the wisdom we are talking about has to come from within ultimately. Some of my work is devoted to trying to help graduate-degree candidates in business administration. We want to give them a process and vehicle for self-assessment, so they can become aware of their own needs and aspirations. That sounds fairly simple and prosaic, but it really isn't. When we get through, we find a lot of students, for instance, who thought they wanted to go into investment banking when they began at Tuck and then realized, after going through an assessment project, that they had made that choice for everybody but themselves. Or someone might come to the realization that a particular area of consulting he thought he wanted to go into wasn't what he wanted at all, because it didn't afford the possibility of any kind of family life.

So the importance of knowing one's self, however much a cliche that might be, is still very true. We all make compromises in that area, we all kid ourselves, and we all adopt other people's definition of success to some extent. We are all Willy Loman to some degree. You remember in Death of a Salesman how Willy, who proudly proclaimed he could sell everywhere, ended up committing suicide. At the time of the funeral his son Biff said his father never knew who he was. A tragic life, a failed life, for that very reason, I suspect. But we do learn who we are, and the work I am involved in is to get people who are looking to the future to define success in more comprehensive and personal terms than is usually done.

Part of what I am doing in my research and clinical work involves dealing with executives who have succeeded by conventional standards and yet have experienced failure in their personal lives and to some extent in their professional lives also. I have to speak as a kind of mental health professional in my own attempt to define what has made life successful for the patients who have done well or for the colleagues and friends whom I see as being successful. The first thing, I think, is a kind of balance. Freud was once asked,

"What is a healthy, successful person?" And he said, "It is somebody who can love and who can work." In a lot of ways, Freud said it all in that particular context. Often, however, we think of work as the only part of life that involves succeeding, and within that concept we define work very, very narrowly. We set a particular career trajectory and think we have to make a certain position by a certain age or we're not successful. That's a fallacy. To be involved in relationships that are generative and giving, and productive of growth in other people, would in fact lead to our own growth, development, and success.

When questioned in my research, senior executives talk about what they see as success and about their greatest regrets, and almost without fail the men who are in their mid- to late 40's talk about what they have or haven't been able to do with their families; and a lot of their sense of personal success involves the quality of those relationships. If they somehow slugged it out and made it to the top, as a kind of lonely victor, very few of them actually end up feeling successful. What is needed, I think, is the balance I mentioned - balance between achievement and affiliation. Undergraduates who have taken psychology here have heard of David McClellan's work, and of his ideas of power motivation, achievement motivation, and affiliation. Are you out for power (i.e. a sense of efficacy), for personal accomplishment, or for good relationships? And the point is that you need all three.

Let me briefly summarize a couple of other points. Perspective is another quality possessed by people I see as successful, and as part of that there is a sort of balance between altruism and self-interest. Helen Deutsch, a very fine woman analyst, once said that "a healthy life is one that is based on a capacity to be altruistic and to be narcissistic, to take care of others and to take care of yourself, and to balance the two off."

Finally, I would mention the quality of being open, of being willing to change. Erik Erikson, a psychoanalyst and my first mentor in the field, talks about the capacity to remain tentative, a quality he sees as the cornerstone of a healthy personality. A colleague of mine on the double occasion of his 50th birthday and his election to the presidency of the American Psychological Association announced, "I am 50 years old today and I do not yet know what I am going to be when I grow up." He is one of the most open and vital and successful persons I know. Paul Tillich, the theologian, talks about wholeness and sees it as the quality of a person who has flexible boundaries, who takes in new experiences, and who is willing to try new options in life.

A final thought worth stating is simply that the people I see as successful do not take themselves too seriously. They have balance and overall perspective and a sense of humor. Oscar Wilde said it all quite well when he observed, "Life is much too important to be taken seriously."

Robert C. Watson Jr. '59

Owner and Manager, Lou's Restaurant, Hanover, N.H.; formerly with IBM

I have gone through two phases of "success." The first was going the traditional route via the large corporation. I achieved in large measure the goals I had set for myself. But something was missing. I wasn't getting what I expected from "suc- cess." So I went through a six-year period redefining my goals. This led to my leaving the mother womb of a large corporation, shedding its golden handcuffs, and going out on my own.

I believe "success" is as much a process as a goal to be reached. Change is the only constant. You have to be able to move with the changing times. I constantly alter my concept of a successful life to keep it in focus with an ever-changing reality. I measure my success by the ratio of inner peace versus stress or anxiety over a given period of time.

Do I consider myself successful now? Well, I feel successful. I was free to settle anywhere in the world and I am living where I want to be right now. It didn't matter that we didn't know what we were going to do to earn a living once we got to Hanover. I have my own brand-new business. It's a game. It requires a lot of close attention, but it has integrity and it is paying the bills. People love to talk about food.

My wife, Ann, and my two sons are selfsufficient, somewhat emancipated, learnmg good skills, paying their own way, feeling good about themselves and about the family as a unit. This represents a major change from the single earner supportmg a family of four while dependent on a corporation for our well-being. Self-sufficiency or greater independence is an important goal in achieving my new success. I now have many fewer dependencies and there is measurable progress toward gaining more control over my life. By all these yard marks, I am a lot more successful than I was two years ago, or 10 or 15 years ago. I hope to be more successful next year.

I remember an article that appeared in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE ten years ago or so about Dimitri Gerakaris, a Dartmouth grad who chose to become a blacksmith. And there I was commuting two hours a day in my three-piece suit and wingtipped shoes and very "successful." I remember thinking "Dimitri is the real success." The article kindled in me the belief that I could do anything I really wanted to do.

The trappings of success as we knew them in the early 60's are not so important today. We now realize there are many different ways of measuring success. I believe that Dartmouth allows that independent spark to glow much more now than it did in previous years. I also read with admiration about the progress of Dartmouth grads (in Give a Rouse) who achieve the more traditional successes. You know they are doing their jobs well and you hope the other parts of their lives are as successful.

Gregory Hemberger '70

Architect, with Banwell, White, Arnold & Hemberger, Hanover, N.H.

For a definition of success I turned, as I often do, to Webster's dictionary. Of the two definitions given, the first is the one I identify with more closely. It says: "A favorable or prosperous termination of attempts or endeavors," which has an element of happiness and growth in it. The second definition, "Attainment of wealth, position, honors or the like," is more stereotypical. For me, success has to do with goal definition and achievement; and in that respect I guess I would consider myself successful. But I am also at a point where I am reevaluating how I got where I am and where I am going.

My interest in architecture developed when at age 15 I took a part-time job with an architectural firm in New Haven, and at that time I really began my commitment to becoming an architect. So I came to Dartmouth with that very linear and narrowly focused goal, but also with the intent of broadening my experience and exposure in other areas. Looking back, I am not sure that I took full advantage of those opportunities. However, I went on to graduate school after Dartmouth, and then came back to Hanover to practice in a small firm, primarily because I think this is a good place to live. I consider myself fortunate to be doing what I like to do, and to be living in a place where I like to live.

In terms of attainment of goals, I can claim success. Recently I have received some recognition for work I've done, and this has had a curious effect on me. It has increased the expectations of others as to what I am able to do; and if success breeds success, it also breeds lack of time, a certain amount of stress, and a reassessment of goals. Do I really want to spend all my time being a successful architect or, as it turns out, do I want to do some of the other things that have emerged as desirable in respect to lifestyle, family, children, and play? Equally important, if not more important, is one's overall feeling of well-being, which is part of success. Coming back to that first definition in Webster's, I read into it a sense of well-being that is not necessarily attained by striving for or reaching positions of power or status or wealth.

The idea that success is related to a sense of well-being, derived from one's achievements and from making a contribution, is nurtured at Dartmouth. That's how I remember it. The liberal-arts exposure to varied disciplines and different ways of thinking provides a good basis for having a successful life. I went to Dartmouth at a time when we were in the middle of the Vietnam war and there was a tremendous amount of questioning of values, both personal and obviously on the national and international levels. At that time, success in the traditional sense was somewhat scorned, at least the business version of it was. Dartmouth then was asking some healthy questions. I remember that when I applied to Dartmouth, I was asked what I considered my greatest personal strength, what I considered my greatest personal weakness, and whom I most admired and why. Those are questions that continue to come up throughout a Dartmouth education and experience. They lead one to appreciate the importance of the self-evaluation that Rick Gilkey spoke about. The reassessment of one's goals, of where one is in terms of personal well-being, is a very large factor in whether or not one feels himself or herself to be leading a successful life.

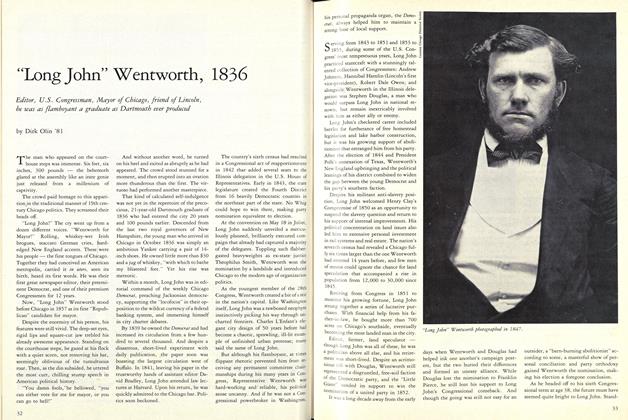

E. R. "Skip" Sturman '70, director of career and employment services, in his College Hall office,discussing career questions with a student.

Bob Watson '59, formerly with IBM in California, now equates success with owning andmanaging the popular Lou's Restaurant in Hanover.

£• R- "Skip" Sturman spends much of his time coun-seling Dartmouth students in his job as Director ofCareer and Employment Services. His article is de-rived from a talk he gave in the fall at a CommunityReflections discussion sponsored by the Tucker Foun-dation. fhe other reflections upon success were heardat a follow-up panel discussion sponsored by theDartmouth Society of Business and Finance andmoderated by Sturman.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

March 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

March 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

March 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Article

ArticleSetting the Record Straight: A Senior-Year Perspective

March 1983 By Libby Schmeltzer '83 -

Sports

SportsSports

March 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticlePhilosopher Coach

March 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN AT LUGING

Sept/Oct 2001 By CAMERON MYLER '92 -

FEATURES

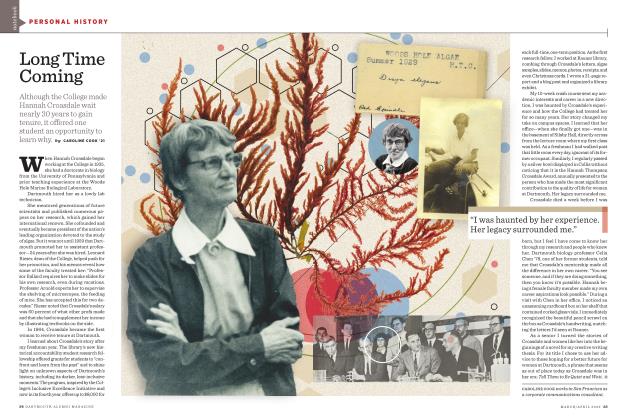

FEATURESLong Time Coming

MARCH/APRIL 2023 By CAROLINE COOK ’21 -

Feature

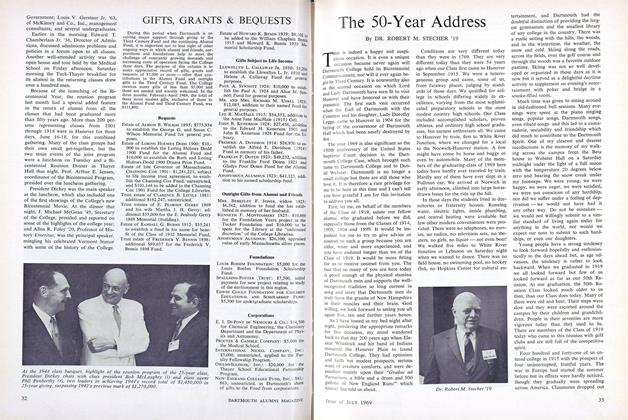

FeatureThe 50-Year Address

JULY 1969 By DR. ROBERT M. STECHER '19 -

Feature

FeatureFishing The River For A Monument

September 1992 By John Scotford '38 -

Cover Story

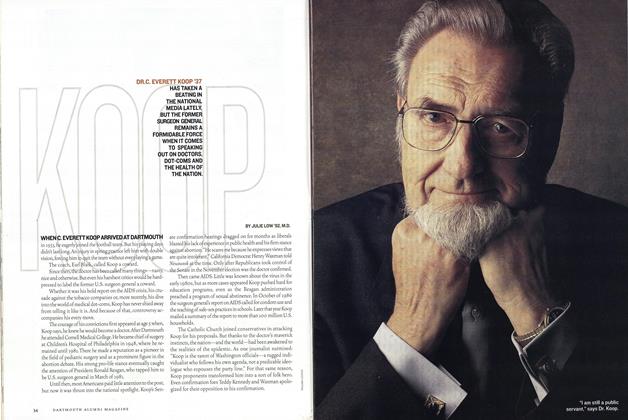

Cover StoryKoop

Jan/Feb 2001 By JULIE LOW ’92, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureCan Education Kill the Movies?

JANUARY 1968 By Maurice Rapf '35