Most Americans take for granted the clean water that flows into their homes and offices. But recently, the devastating effects of modern technology upon once-pure water sources and the ever-increasing demand for that precious liquid have forced communities to expand the search for new wells if the flow is to continue unabated.

Even in some parts of New Hampshire a state not usually considered arid new water sources are sorely needed. And many communities desperate for dependable municipal water supplies are calling on the expertise of BCI Geonetics of Laconia, a company with innovative schemes both to locate water and to protect it.

BCI, in its 11th year, brings everything from a dowser's intuition to space satellite photos to bear in its search for water, according to Dennis S. Albaugh '76, a staff geologist. Central to BCI is the company's new approach to searching for water tapping the large pools found in vertical cracks of bedrock hundreds of feet into the earth.

"It gets complicated," Albaugh said as he explained how BCI selects its well sites. To find the precise spot to dig an act which might well be compared to threading a needle in the dark researchers study volumes of old geology reports, examine rocks unearthed in area construction projects, agonize over contour maps and satellite photos, and scour the area for clues in the dirt and vegetation.

"After all that studying, we put a stake in the ground. If that stake (the digging site) is off one foot this way or the other, we may miss the fissure," the geologist said.

The process sounds exhaustive, and it has to be. BCI is searching for wells many hundreds of feet deep that can consistently deliver as much as a million gallons of water a day. (The biggest to date, according to Albaugh, was a project in Salem, N.H., that located 1.7 million gallons per day.)

Tuck-educated Peter D. Hofman .'68 (M.B.A. '69), the company's executive vice president, described the flow of rainwater seeping through the earth in lay terms: "Many well-drillers tap capillaries," he said. "We are looking for the arteries and veins which those capillaries feed."

Since water cannot be seen beneath the earth's surface, well-drilling is something of a wager. There is always the chance that one could be looking for water where it isn't. To minimize this risk, traditional water-seeking methods concentrate on obtaining water near the surface: building massive gathering pools or relatively shallow ground-water wells. In comparison, the BCI approach involves considerably greater risk but also greater payoff because of a special marketing system.

BCI, quite simply, offers "no risk" prospecting to potential clients. Albaugh, Hofman, and the rest of the company discuss with the community (or industrial park or mall) how much water is needed, and then BCI fronts the money for finding it. If the necessary amount of water cannot be found, BCI pays; if it can, the company sells the water to the client at a pre-determined price per gallon, with minimum amounts and the contract period also set in advance.

"We buy the rights to develop the water resource and the landowner gets royalty payments like in the oil business," Hofman explained. "In turn, he has to agree not to degrade the land with septic systems and certain chemicals."

The BCI marketing system creates a threeway synergistic effect: The towns get the water they need, the landowners get royalties to ensure their long-term cooperation, and BCI makes a profit by managing and maintaining the water flow through the contract period.

The geologist and the businessman have come to BCI from quite different backgrounds. Hofman spent two years in Peru with the Peace Corps after graduating from business school ("seriously lowering the starting salary of my Tuck graduating class," he joked). Hofman then returned to New Hampshire and worked on natural resource projects and land use plans during much of the seventies. Albaugh, who received a master's degree in geophysics and geotectonics from Cornell, is the co-author of numerous papers on the structural geology of mountain ranges in the Northeast. A Hanover native, Albaugh has also been a guest lecturer in Dartmouth's earth sciences department.

At BCI their divergent backgrounds converge. Both enjoy the outdoors with their families; both have taken on the challenge of building their own homes in the New Hampshire woods (in fact Albaugh and family were still nailing up sheetrock at last report); and both are concerned about how their work can be transferred to some of the world's most water-starved regions. In fact, they said BCI intends to start its first international project next year in Africa.

"I think we are doing something important for people. We're not only finding a resource, we're protecting a resource," Hofman mused. "I believe we can also have a real impact on the well-being of people."

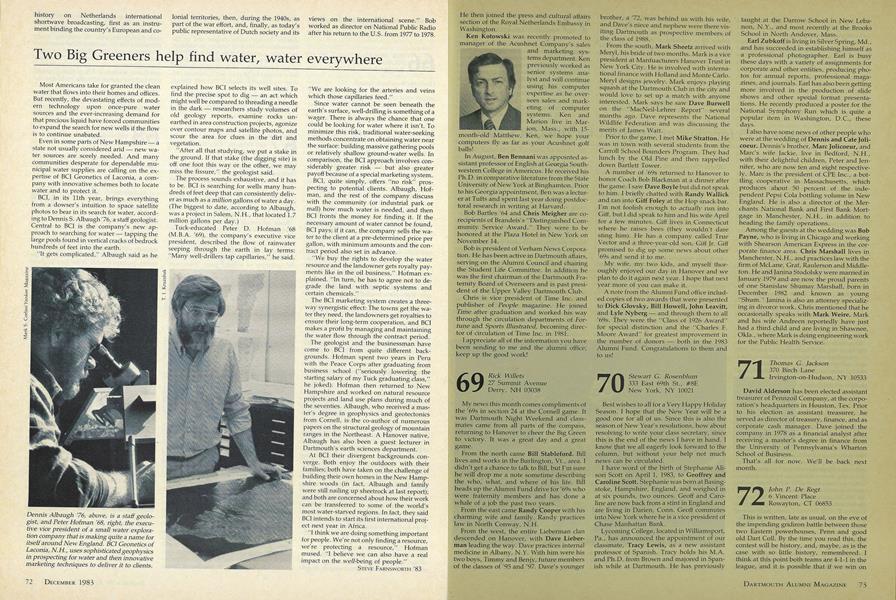

Dennis Albaugh '76, above, is a staff geologist,and Peter Hofman '68, right, the executivevice president of a small water exploration company that is making quite a name foritself around New England. BCI Geonetics ofLaconia, N.H., uses sophisticated geophysicsin prospecting for water and then innovativemarketing techniques to deliver it to clients.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePsycho-Social Dynamics and the Prospects for Mankind

December 1983 By Charles E. Osgood '39 -

Feature

FeatureMaris Bryant Pierce: A Seneca Chief at Dartmouth

December 1983 By Howard A. Vernon -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

December 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

December 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

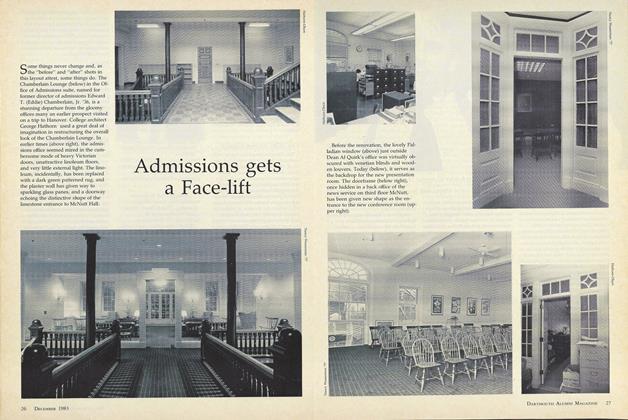

FeatureAdmissions gets a Face-lift

December 1983 By Nancy Wasserman -

Sports

SportsSports

December 1983 By Kathy Slattery

Steve Farnsworth '83

-

Article

ArticleA Neglected Admonition

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleThe Class of Nodding Acquaintances

November 1982 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleSenior hockey: through the golden years on silver blades

November 1982 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleSanford Gottlieb '46: "An American pacifist leader"

APRIL 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleUndergraduate Chair

JUNE 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleFormer "Wearer of the Green" now sports black and white

OCTOBER, 1908 By Steve Farnsworth '83