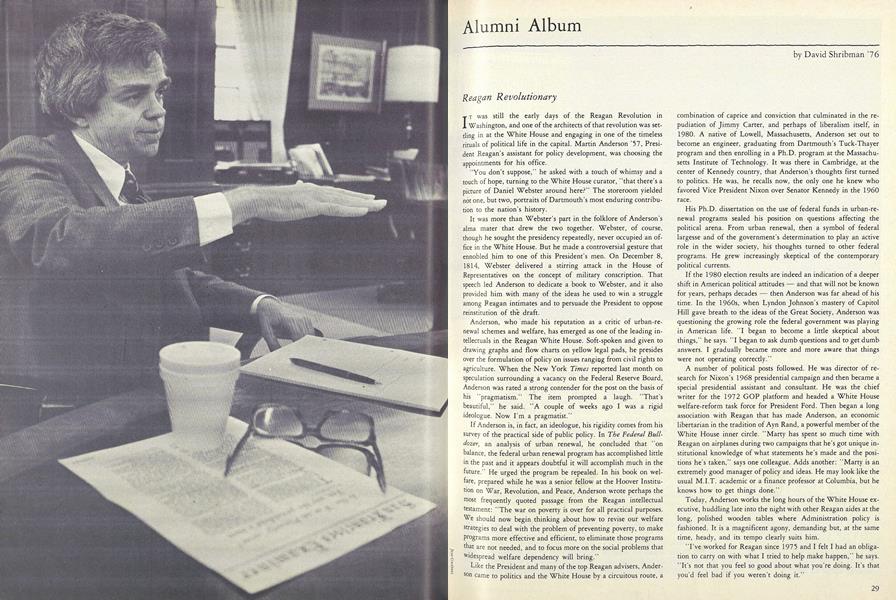

I T was still the early days of the Reagan Revolution in Washington, and one of the architects of that revolution was settling in at the White House and engaging in one of the timeless rituals of political life in the capital. Martin Anderson '57, President Reagan's assistant for policy development, was choosing the appointments for his office.

"You don't suppose," he asked with a touch of whimsy and a touch of hope, turning to the White House curator, "that there's a picture of Daniel Webster around here?" The storeroom yielded not one, but two, portraits of Dartmouth's most enduring contribution to the nation's history.

It was more than Webster's part in the folklore of Anderson's alma mater that drew the two together. Webster, of course, though he sought the presidency repeatedly, never occupied an office in the White House. But he made a controversial gesture that ennobled him to one of this President's men. On December 8, 1814, Webster delivered a stirring attack in the House of Representatives on the concept of military conscription. That speech led Anderson to dedicate a book to Webster, and it also provided him with many of the ideas he used to win a struggle among Reagan intimates and to persuade the President to oppose reinstitution of the draft.

Anderson, who made his reputation as a critic of urban-renewal schemes and welfare, has emerged as one of the leading intellectuals in the Reagan White House. Soft-spoken and given to drawing graphs and flow charts on yellow legal pads, he presides over the formulation of policy on issues rangiqg from civil rights to agriculture. When the New York Times reported last month on speculation surrounding a vacancy on the Federal Reserve Board, Anderson was rated a strong contender for the post on the basis of his "pragmatism." The item prompted a laugh. "That's beautiful," he said. "A couple of weeks ago I was a rigid ideologue. Now I'm a pragmatist."

If Anderson is, in fact, an ideologue, his rigidity comes from his survey of the practical side of public policy. In The Federal Bulldozer, an analysis of urban renewal, he concluded that "on balance, the federal urban renewal program has accomplished little in the past and it appears doubtful it will accomplish much in the future." He urged the program be repealed. In his book on welfare, prepared while he was a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, Anderson wrote perhaps the most frequently quoted passage from the Reagan intellectual testament: "The war on poverty is over for all practical purposes. We should now begin thinking about how to revise our welfare strategies to deal with the problem of preventing poverty, to make programs more effective and efficient, to eliminate those programs that are not needed, and to focus more on the social problems that widespread welfare dependency will bring."

Like the President and many of the top Reagan advisers, Anderson came to politics and the White House by a circuitous route, a combination of caprice and conviction that culminated in the repudiation of Jimmy Carter, and perhaps of liberalism itself, in 1980. A native of Lowell, Massachusetts, Anderson set out to become an engineer, graduating from Dartmouth's Tuck-Thayer program and then enrolling in a Ph.D. program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It was there in Cambridge, at the center of Kennedy country, that Anderson's thoughts first turned to politics. He was, he recalls now, the only one he knew who favored Vice President Nixon over Senator Kennedy in the 1960 race.

His Ph.D. dissertation on the use of federal funds in urban-renewal programs sealed his position on questions affecting the political arena. From urban renewal, then a symbol of federal largesse and of the government's determination to play an active role in the wider society, his thoughts turned to other federal programs. He grew increasingly skeptical of the contemporary political currents.

If the 1980 election results are indeed an indication of a deeper shift in American political attitudes and that will not be known for years, perhaps decades then Anderson was far ahead of his time. In the 19605, when Lyndon Johnson's mastery of Capitol Hill gave breath to the ideas of the Great Society, Anderson was questioning the growing role the federal government was playing in American life. "I began to become a little skeptical about things," he says. "I began to ask dumb questions and to get dumb answers. I gradually became more and more aware that things were not operating correctly."

A number of political posts followed. He was director of research for Nixon's 1968 presidential campaign and then became a special presidential assistant and consultant. He was the chief writer for the 1972 GOP platform and headed a White House welfare-reform task force for President Ford. Then began a long association with Reagan that has made Anderson, an economic libertarian in the tradition of Ayn Rand, a powerful member of the White House inner circle. "Marty has spent so much time with Reagan on airplanes during two campaigns that he's got unique institutional knowledge of what statements he's made and the positions he's taken," says one colleague. Adds another: "Marty is an extremely good manager of policy and ideas. He may look like the usual M.I.T. academic or a finance professor at Columbia, but he knows how to get things done."

Today, Anderson works the long hours of the White House executive, huddling late into the night with other Reagan aides at the long, polished wooden tables where Administration policy is fashioned. It is a magnificent agony, demanding but, at the same time, heady, and its tempo clearly suits him.

"I've worked for Reagan since 1975 and I felt I had an obligation to carry on with what I tried to help make happen," he says. "It's not that you feel so good about what you're doing. It's that you'd feel bad if you weren't doing it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

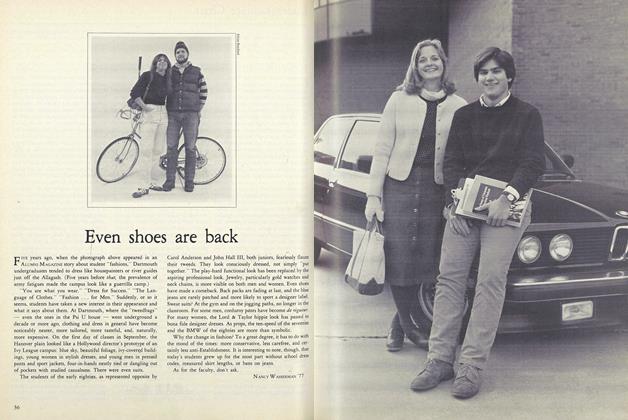

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65

David Shribman '76

-

Article

ArticleFrench Verbs and Javelin Throws

April 1974 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleInn Greeters With a Window on the Green

December 1975 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleGod-fearing Surgeon General

APRIL 1982 By David Shribman '76 -

Books

BooksAdding to the Mosaic

SEPTEMBER 1982 By David Shribman '76 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Album

MARCH 1983 By David Shribman '76 -

Features

Features“His Life Was a Gift”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2023 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76