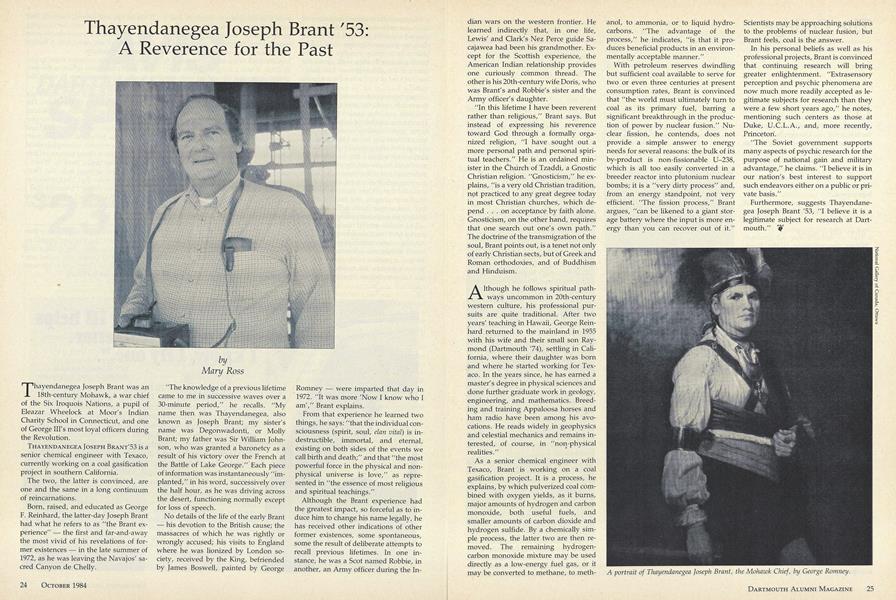

Thayendanegea Joseph Brant was an 18th-century Mohawk, a war chief of the Six Iroquois Nations, a pupil of Eleazar Wheelock at Moor's Indian Charity School in Connecticut, and one of George Ill's most loyal officers during the Revolution.

THAYENDANEGEA JOSEPH BRANT'53 is a senior chemical engineer with Texaco, currently working on a coal gasification project in southern California.

The two, the latter is convinced, are one and the same in a long continuum of reincarnations.

Born, raised, and educated as George F. Reinhard, the latter-day Joseph Brant had what he refers to as "the Brant experience" the first and far-and-away the most vivid of his revelations of former existences in the late summer of 1972, as he was leaving the Navajos' sacred Canyon de Chelly.

"The knowledge of a previous lifetime came to me in successive waves over a 30-minute period," he recalls. "My name then was Thayendanegea, also known as Joseph Brant; my sister's name was Degonwadonti, or Molly Brant; my father was Sir William Johnson, who was granted a baronetcy as a result of his victory over the French at the Battle of Lake George." Each piece of information was instantaneously "implanted," in his word, successively over the half hour, as he was driving across the desert, functioning normally except for loss of speech.

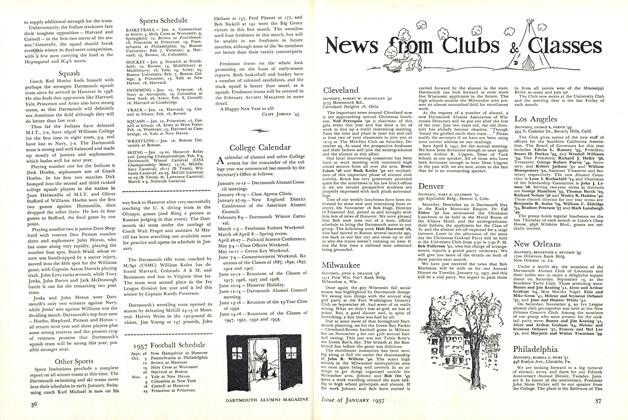

No details of the life of the early Brant his devotion to the British cause; the massacres of which he was rightly or wrongly accused; his visits to England where he was lionized by London society, received by the King, befriended by James Boswell, painted by George Romney were imparted that day in 1972. "It was more 'Now I know who I am'," Brant explains.

From that experience he learned two things, he says: "that the individual consciousness (spirit, soul, elan vital) is indestructible, immortal, and eternal, existing on both sides of the events we call birth and death;" and that "the most powerful force in the physical and nonphysical universe is love," as represented in "the essence of most religious and spiritual teachings."

Although the Brant experience had the greatest impact, so forceful as to induce him to change his name legally, he has received other indications of other former existences, some spontaneous, some the result of deliberate attempts to recall previous lifetimes. In one instance, he was a Scot named Robbie, in another, an Army officer during the Indian wars on the western frontier. He learned indirectly that, in one life, Lewis' and Clark's Nez Perce guide Sacajawea had been his grandmother. Except for the Scottish experience, the American Indian relationship provides one curiously common thread. The other is his 20th-century wife Doris, who was Brant's and Robbie's sister and the Army officer's daughter.

"In this lifetime I have been reverent rather than religious/' Brant says. But instead of expressing his reverence toward God through a formally organized religion, "I have sought out a more personal path and personal spiritual teachers." He is an ordained minister in the Church of Tzaddi, a Gnostic Christian religion. "Gnosticism," he explains, "is a very old Christian tradition, not practiced to any great degree today in most Christian churches, which depend ... on acceptance by faith alone. Gnosticism, on the other hand, requires that one search out one's own path." The doctrine of the transmigration of the soul, Brant points out, is a tenet not only of early Christian sects, but of Greek and Roman orthodoxies, and of Buddhism and Hinduism.

Although he follows spiritual pathways uncommon in 20th-century western culture, his professional pursuits are quite traditional. After two years' teaching in Hawaii, George Reinhard returned to the mainland in 1955 with his wife and their small son Raymond (Dartmouth '74), settling in California, where their daughter was born and where he started working for Texaco. In the years since, he has earned a master's degree in physical sciences and done further graduate work in geology, engineering, and mathematics. Breeding and training Appaloosa horses and ham radio have been among his avocations. He reads widely in geophysics and celestial mechanics and remains interested, of course, in "non-physical realities."

As a senior chemical engineer with Texaco, Brant is working on a coal gasification project. It is a process, he explains, by which pulverized coal combined with oxygen yields, as it burns, major amounts of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, both useful fuels, and smaller amounts of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide. By a chemically simple process, the latter two are then removed. The remaining hydrogencarbon monoxide mixture may be used directly as a low-energy fuel gas, or it may be converted to methane, to methanol, to ammonia, or to liquid hydrocarbons. "The advantage of the process," he indicates, "is that it produces beneficial products in an environmentally acceptable manner."

With petroleum reserves dwindling but sufficient coal available to serve for two or even three centuries at present consumption rates, Brant is convinced that "the world must ultimately turn to coal as its primary fuel, barring a significant breakthrough in the production of power by nuclear fusion." Nuclear fission, he contends, does not provide a simple answer to energy needs for several reasons: the bulk of its by-product is non-fissionable U-238, which is all too easily converted in a breeder reactor into plutonium nuclear bombs; it is a "very dirty process" and, from an energy standpoint, not very efficient. "The fission process," Brant argues, "can be likened to a giant storage battery where the input is more energy than you can recover out of it." Scientists may be approaching solutions to the problems of nuclear fusion, but Brant feels, coal is the answer.

In his personal beliefs as well as his professional projects, Brant is convinced that continuing research will bring greater enlightenment. "Extrasensory perception and psychic phenomena are now much more readily accepted as legitimate subjects for research than they were a few short years ago," he notes, mentioning such centers as those at Duke, U.C.L.A., and, more recently, Princeton.

"The Soviet government supports many aspects of psychic research for the purpose of national gain and military advantage," he claims. "I believe it is in our nation's best interest to support such endeavors either on a public or private basis."

Furthermore, suggests Thayendanegea Joseph Brant '53, "I believe it is a legitimate subject for research at Dartmouth."

A portrait of Thayendanegea Joseph Brant, the Mohawk Chief, by George Romney.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

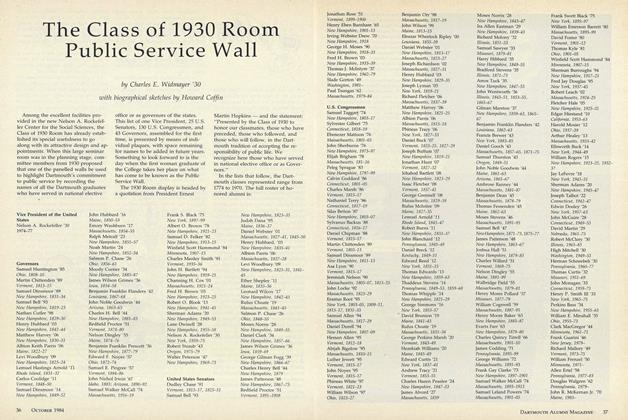

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

October 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGeared for Success

October 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

October 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

October 1984 By George O'Connell -

Article

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

October 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleGetting Better with Age

October 1984 By Gayle Gilman '85

Mary Ross

-

Article

ArticleTriple-Threat Academician

DECEMBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleTV Journalist

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

DECEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleArts Catalyst

MARCH 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

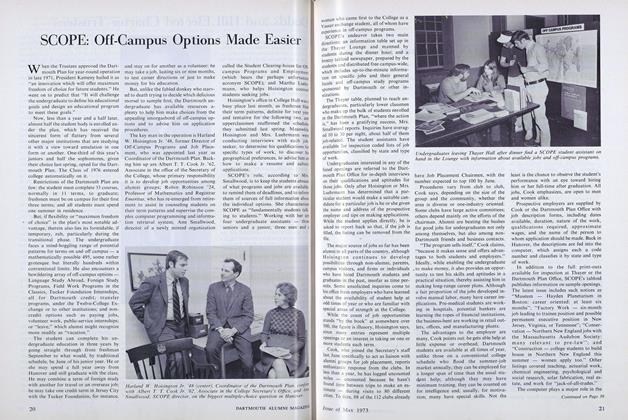

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

MAY 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

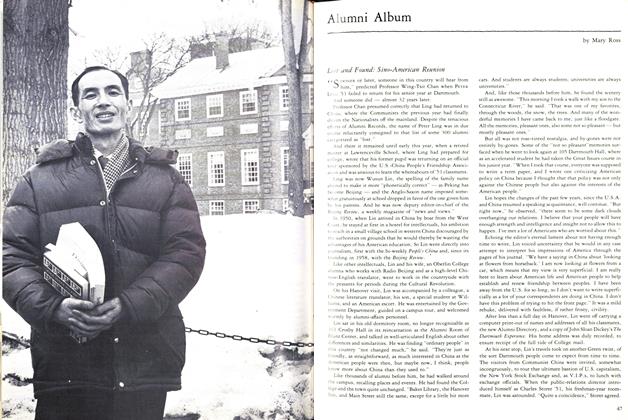

ArticleLost and Found: Sino-American Reunion

JUNE 1982 By Mary Ross