The poet Richard Eberhart recently turned 80, though you'd never know it by talking to him. As one of America's most respected poets, author of more than 20 books, and winner of nearly every major literary prize (including the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award), he might well sit back and rest on his laurels. Instead, he's as excited about poetry as ever. His new book, The Long Reach, has been published, to coincide with his eightieth birthday: and it contains 240 pages of new poetry! "I didn't want to bring out another slim volume," says Eberhart. "I wanted, this one time, topresent everything I've written in recent years. It was time that a book showed the range and variety of my work." If the advance review in Publisher's Weekly is any indication of the critical reception Eberhart's book will get, his ambitions have paid off. "The Long Reach is a major work and a key to his thought," says the reviewer. "This urgent yet serene volume of his twilight years is the crown of the poet's career."

I first met Eberhart nine years ago when I came to Dartmouth College as his understudy, a sort of "junior poet-in-residence." Since first reading Eberhart's classic poem, "The Groundhog," in a ninth grade English class, I had loved his work. It struck me then, as it does twenty years later, that Eberhart succeeds in the way all great poets succeed by communicating deep and serious concerns in the simplest, most evocative language. "The Groundhog" begins:

In June, amid the golden fields, I saw a groundhog lying dead. Dead lay he; my senses shook, And mind outshot our naked frailty.

The reader feels the weight of centuries of English verse behind those four-beat lines. The ending, which lives permanently in my head and resurfaces at odd moments each year, still strikes me as one of the glories of contemporary poetry:

I stood there in the whirling summer, My hand capped a withered heart, And thought of China and of Greece, Of Alexander in his tent; Of Montaigne in his tower, Of Saint Theresa in her wild lament.

Those lines thrill me now as much as when I first read them. They have a tautness about them and wonderful texture.

Arriving at Dartmouth, I naturally looked forward to meeting Mr. Eberhart. He was 72 then, I was 26. It occurred to me that he, like many famous writers, might not like having a younger writer on the scene generational struggles are as common to literature as to national politics. I had, in fact, worked myself into a mild frenzy over meeting him, when, several weeks into the first term, a knock came to my office door in Sanborn House. "Hi!" called a stout man with a cherubic face. "I'm Dick Eberhart. You must be...."

He sat himself down immediately, lit up his ever-present pipe, and began chattering about poets and poetry like nothing I'd heard before or have heard since. I wondered if it were really possible that the strong, contemplative, philosophic poetry of Richard Eberhart had come out of this unlikely man. The high, crackly voice startled me. Eberhart was a small cyclone of talk, and I was whirled about for two straight hours before he asked me if I'd like to have dinner with him at home. I said I would, whenever it was convenient. "It's always convenient," he said. "Let's go home now. Betty will love it."

That remark proved characteristic of the man and his approach to life and art. He is unfailingly generous, open to every kind of new idea or experience. His energy is unfathomable: Eberhart is himself a force of nature. He maintains in old age the wide-eyed enthusiasm for newness one sees in a college freshman, talking about Plato, say, as though he'd just met the old boy while crossing the Green. It seems unlikely that Dick Eberhart was ever any different, but he says he was: "I was nurtured in the Academy, first at Dartmouth, then Cambridge and Harvard all bastions of tradition and traditionalism. I began my career writing for intellectuals critics and professors people who shared a certain elite view of the world. I identified with the establishment. It's only in the past fifteen years or so that I've had a shift of emphasis toward a more democratic principle."

A good observer would have seen this shift to the wider public coming. Richard Eberhart was the first of the so-called "established" poets ("No poet ever considered himself established," he says.) to welcome the Beat Generation into the fold. As early as 1956, when he wrote a piece on "West Coast Rhythms" for the New York Times, he seemed to be embracing democratic poetic principles. He singled out an unknown group of San Francisco writers: "They are finely alive, they believe something new can be done with the art of poetry, they are hostile to gloomy critics, and the reader is invited to look into and enjoy their work as it appears. They have exuberance and a young will to kick down the doors of older consciousness and established practice in favor of what they think is vital and new." Eberhart singled out a 29-year-old poet named Allen Ginsberg as one especially worth reading. He said of "Howl," Ginsberg's classic "Beat" poem: "It is a howl against everything in our mechanistic civilization which kills the spirit.... It lays bare the nerves of suffering and spiritual struggle. Its positive force and energy come from a redemptive quality of love." For a conservative Ivy Leaguer in the mid-fifties, this was revolutionary talk.

Today, Eberhart has lost none of his fervor. "I insist that poetry be understood," he says. "Take Shakespeare as an example. His poetry moves into the highest and subtlest regions of thought and feeling, yet he never shuts out the common reader." This hypothetical "common reader" is never shut out of Eberhart's work either. In "Passage," for instance, a poem in his latest collection, he writes with passionate understanding of time, a subject of peculiar force to a man at 80:

Time! It rushed over us when we were striplings, Over us in mid-life, over us in age.

Time the smacker without a grudge. It is in the air surrounding my fingers,

It is in my mind in my skull, It is in my legs walking and my voice talking.

"Poetry should be simple and passionate and deal with the truths of everyday life," says Eberhart; as "Passage" shows, he has been uncannily successful in putting theory and practice together. "For 40 years now Dick Eberhart has been one of the solid figures in American poetry," says his publisher, James Laughlin. "The present American poetry scene is a morass of mediocrity, where second- and third-raters are touted for acclaim and awards which they do not deserve. With time, Eberhart will bury all these poetasters." Strong words! But many of Eberhart's peers echo these sentiments. "I think he's just one of the best poets we have," says Robert Penn Warren. "He's written a dozen of the best poems produced by any American in the past three or four decades."

As far as prizes, publications, and acclaim go, Richard Eberhart sits somewhere near the top of the heap. But this has not always been the case. "I lived in real obscurity for years," the poet says. "I never had an academic position till I was nearly 50, when Theodore Roethke asked me to replace him for a term at the University of Washington." Until then, Eberhart was more or less on his own. A native of Austin, Minnesota, Eberhart had a classic small town upbringing. He came east to Dartmouth, graduating in 1926, then circled the world on a tramp steamer. He spent a time at Cambridge University in England, where he was befriended by most of that country's leading poets William Empson, W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender, and others. Getting his M.A. from Cambridge, he set off to Harvard for doctoral studies. But his father's

business went bankrupt with the Depression, and Eberhart's dreams fizzled. He searched desperately for a job, at one point tutoring the son of the King of Siam, then living in this country. A break came when St.

Mark's, a prep school near Boston, offered him a job as English master. He spent eight years there, at one time teaching Robert Lowell, who called Eberhart "my first important mentor and model." With the coming of the war, St. Mark's fell upon hard times. The headmaster wrote Eberhart that they were cutting their budget and could not ask him back. Thus, at 36, Eberhart was out in the cold, jobless and still quite unknown as a poet.

He finally got an offer from another prep school near Boston, but two events changed his life suddenly: he met a woman, Betty Butcher, herself an elementary school teacher in Cambridge and the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Eberhart married Betty (one of the wisest, kindest women I know), and he signed up with the Navy as a gunnery instructor for aviators. I think Dick was lucky in both instances. The marriage proved not good but wonderful. Betty's quick wit and natural openness match Dick's own temperament beautifully. Whenever he gets a little too abstract or ponderous, Betty is quick to deploy her deflationary wit. If Dick gets depressed or upset, Betty rapidly puts things in perspective. I recall a time recently when Dick was excluded from a major anthology of American poetry. He felt devastated for weeks, and no one could talk to him. I happened to be at their house in Hanover when Betty took him, literally, by the collar: "For , heaven's sake, Dick! You're the one who always says that anthologies are stupid they cater to fashion, and misrepresent everything. If your poetry is any good, it will last. If it's not, what happens to your work doesn't matter." Dick listened and sat down to write the poems now included in The Long Reach.

The war brought Eberhart into contact with issues of real weight, with life and death, and served as catalyst to many of his finest poems, including "The Fury of Aerial Bombardment," which begins: You would think the fury of aerial bombardment Would rouse God to relent; the infinite spaces Are still silent. He looks on shockpried faces. History, even, does not know what is meant.

As an aviation gunnery instructor, he prepared young fliers for bombing missions. In the poem, he asks: "Was man made stupid to see his own stupidity?" He ends on a stark personal note another superb moment in contemporary poetry: Of Van Wettering I speak, and Averill, Names on a list, whose faces I do not recall But they are gone to early death, who late in school Distinguished the belt feed lever from the belt holding pawl.

After the war, Eberhart's fortunes changed. He became, for a while, vice president of his wife's floor wax company a poet-businessman, like his friend Wallace Stevens. Then came the invitation from Roethke to teach in Washington; this offer led to others from Princeton and Dartmouth, where in 1956 Eberhart became Poet-in-Resi-dence, a position he still holds. "It was in my early fifties that I won my first real recognition as a poet, too," he says. His first Selected Poems always an important sign of a poet's arrival appeared in 1951. Book followed book, including the Pulitzerwinning Selected Poems 1930-1965 and the National Book Award-winning Collected Poems 1930-1976, which gathers in one volume all the well-known poems and many of lesser fame. "Dick has always been uneven," says his wife, Betty. "He needs a good editor." But the poet disagrees. "Let posterity, pick and choose. I can't tell what will last and what won't. That's why I've finally decided it was time to bring everything together in this new book, The Long Reach. I believe in every poem there."

Readers will have to pick and choose, as ever in Richard Eberhart's poetry, but this new book contains many poems equal in power and intensity to his very best work. "Harvard Stadium," for example, shows no falling off of poetic energies. It pictures a poet "who was beyond this age" as he watches young men playing football and feels superior to them below, "Struggling back and forth on the turf." They are "captive in their presences," and "Held in bondage by youth's inferiority." With a delightful self-ironic stance, he writes: No matter, now, who won or lost, His musings unnoticed by the spectators. He was a quiet victor at the spectacle, The reddest judge of the rueful scene. So God himself might sit apart, and stare At the antics of the animal man, Seen from above millennia of wars and non-war, Indifferent to the players below.

The severity, whim, and control of this poem is the result of more than half a century's attendance to his craft. Says Allen Ginsberg: "Richard Eberhart has been able to uphold the visionary and platonic world-view in his poetry by his own humble, direct, and openminded presence."

Now the Eberharts divide their time between New Hampshire and the Maine coast, where Dick pilots his cruiser, The Reve, from island to island. He swims every day and writes poems while sitting in a deep Adirondack chair on his pebbly beach. His routine in Hanover except for the swimming, which turns to biking in cooler weather is much the same. He writes, exercises, reads, and leads an enormously prodigious social life. Poets and would-be poets flock from all over the country to his home on Webster Terrace overlooking the Connecticut River. They are treated with a stiff dose of Eberhartiana books, anecdotes, wit, and wisdom. One is likely to be asked to wield a sword given to Dick by an African tribesman or asked to admire a miniature ivory polar bear bestowed on Dick by a worshipful Eskimo in Alaska. Dick's enthusiasm always carries the day, and no one departs from the Eberharts unhappy. "Dick is the most giving of all poets," says James Dickey, poet and old friend. "The wonderful thing about his work and about him is this spontaneous unasked and unasking bestowal of himself to whoever wishes it." At 80, the world looks as fresh and inviting to Richard Eberhart as it did at 20. He will spend the summer in Maine, of course. He plans to write poetry. And he regards life as "an opportunity, a great test, a place for beginnings." Along with his many other admirers, I look forward to reading Richard Eberhart at 90.

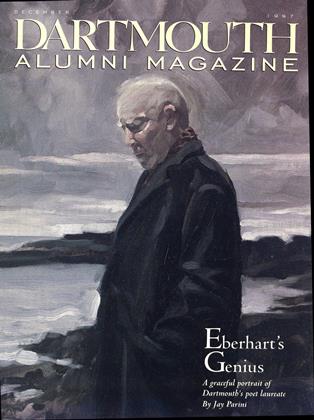

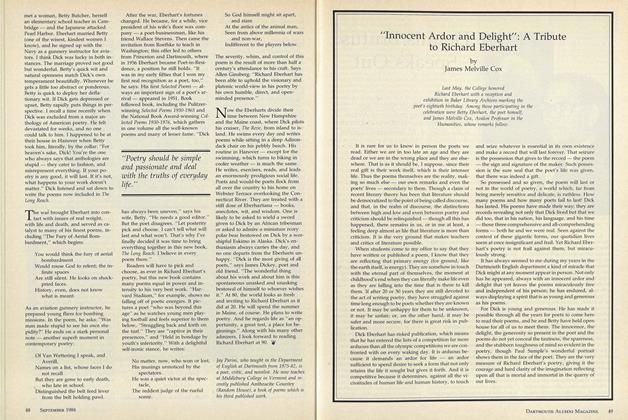

Richard Eberhart sat for this oil portrait of him by another son of Dartmouth, the late Paul Sample '20, former Artist-in-Residence at the College. The painting, presented by Eberhart's 1926 classmates, was completed in 1957 and currently hangs in Sanborn House.

Eberhart succeeds in the way all great poets succeed by communicating deep and serious concerns in the simplest, most evocative language.

He asked me if I'd like to have dinner with him at home. I said I would, whenever it was convenient. "It's always convenient," he said. "Let's go home now. Betty will love it."

"Poetry should be simple and passionate and deal with the truths of everyday life."

Jay Parini, who taught in the Department of English at Dartmouth from 1975-82, is a poet, critic, and novelist. He now teaches at Middlebury College in Vermont and recently published Anthracite Country (Random House), a book of poems which is his third published work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDennis Brutus Speaks Out

September 1984 By Kendal Price '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Montgomery Endowment Finds a Home

September 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature"Three ... Forty-two ... Hut"

September 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature"Innocent Ardor and Delight": A Tribute to Richard Eberhart

September 1984 By James Melville Cox -

Article

ArticleRumblings On Fraternity Row

September 1984 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

September 1984 By Mary Ross

Jay Parini

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLESLIE BUTLER

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Features

FeaturesThe Playmaker

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By DERON SNYDER -

Cover Story

Cover StoryANDREW WEIBRECHT '09

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

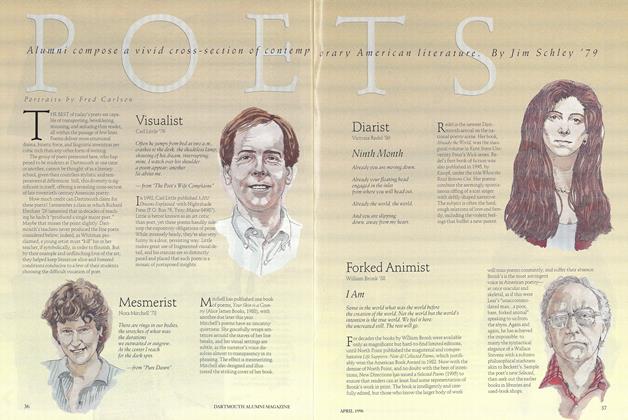

FeaturePOETS

APRIL 1996 By Jim Schley '79 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Invented Dog Running

June 1989 By John F. Anderson '34 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYThe Graduate

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By Ty Burr ’80