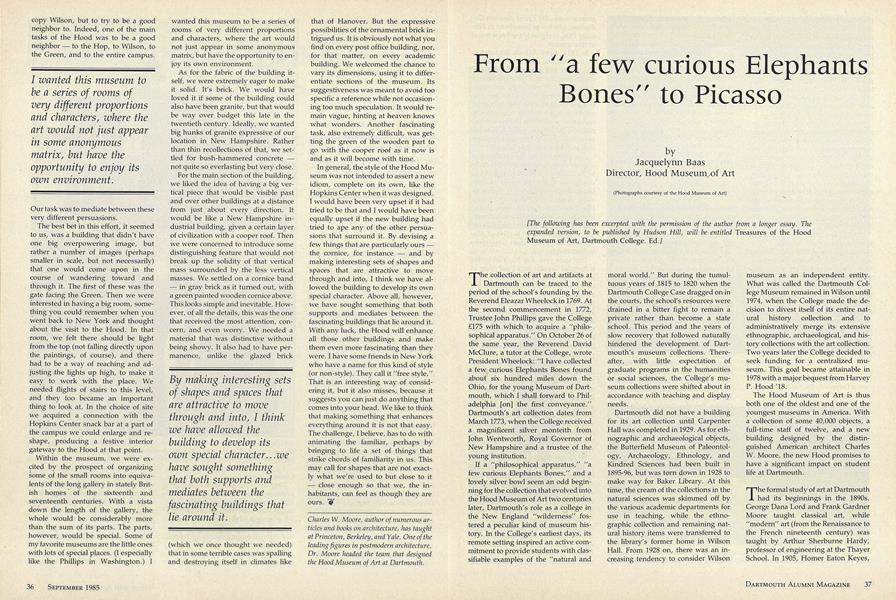

[The following has been excerpted with the permission of the author from a longer essay. Theexpanded version, to be published by Hudson Hill, will be entitled Treasures of the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College. Ed.]

Director, Hood Museum of Art

The collection of art and artifacts at Dartmouth can be traced to the period of the school's founding by the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock in 1769. At the second commencement in 1772, Trustee John Phillips gave the College £175 with which to acquire a "philoophical apparatus." On October 26 of the same year, the Reverend David McClure, a tutor at the College, wrote President Wheelock: "I have collected a few curious Elephants Bones found about six hundred miles down the Ohio, for the young Museum of Dartmouth, which I shall forward to Philadelphia [on] the first conveyance." Dartmouth's art collection dates from March 1773, when the College received a magnificent silver monteith from John Wentworth, Royal Governor of New Hampshire and a trustee of the young institution.

moral world." But during the tumultuous years of 1815 to 1820 when the Dartmouth College Case dragged on in the courts, the school's resources were drained in a bitter fight to remain a private rather than become a state school. This period and the years of slow recovery that followed naturally hindered the development of Dartmouth's museum collections. Thereafter, with little expectation of graduate programs in the humanities or social sciences, the College's museum collections were shifted about in accordance with teaching and display needs. If a "philosophical apparatus," "a few curious Elephants Bones," and a lovely silver bowl seem an odd beginning for the collection that evolved into the Hood Museum of Art two centuries later, Dartmouth's role as a college in the New England "wilderness" fostered a peculiar kind of museum history. In the College's earliest days, its remote setting inspired an active commitment to provide students with classifiable examples of the "natural and

Dartmouth did not have a building for its art collection until Carpenter Hall was completed in 1929. As for ethnographic and archaeological objects, the Butterfield Museum of Paleontology, Archaeology, Ethnology, and Kindred Sciences had been built in 1895-96, but was torn down in 1928 to make way for Baker Library. At this time, the cream of the collections in the natural sciences was skimmed off by the various academic departments for use in teaching, while the ethnographic collection and remaining natural history items were transferred to the library's former home in Wilson Hall. From 1928 on, there was an increasing tendency to consider Wilson museum as an independent entity. What was called the Dartmouth College Museum remained in Wilson until 1974, when the College made the decision to divest itself of its entire natural history collection and to administratively merge its extensive ethnographic, archaeological, and history collections with the art collection. Two years later the College decided to seek funding for a centralized museum. This goal became attainable in 1978 with a major bequest from Harvey P. Hood '18.

The Hood Museum of Art is thus both one of the oldest and one of the youngest museums in America. With a collection of some 40,000 objects, a full-time staff of twelve, and a new building designed by the distinguished American architect Charles W. Moore, the new Hood promises to have a significant impact on student life at Dartmouth.

The formal study of art at Dartmouth had its beginnings in the 1890s. George Dana Lord and Frank Gardner Moore taught classical art, while "modern" art (from the Renaissance to the French nineteenth century) was taught by Arthur Sherburne Hardy, professor of engineering at the Thayer School. In 1905, Homer Eaton Keyes, the second editor of the DartmouthAlumni Magazine, was appointed assistant professor of modern art. Under his leadership, a centralized art department was set up on the top floor of the new, brick Dartmouth Hall (its wooden predecessor had burned to the ground in 1904). Keyes, incidentally, left Dartmouth in 1921 to found and edit the highly successful art magazine, Antiques, which he headed until his death in 1938.

Keyes was succeeded in the art department by George Breed Zug, who added to the curriculum the study of American painting, photography, the graphic arts, the art of the book, and city planning a radically modern curriculum for the time. Under Zug, the department also organized special exhibitions, such as the first exhibition of work by members of the art colony at Cornish, New Hampshire, shown in the Little Theater of Robinson Hall in January 1916.

In 1921, the art department moved to somewhat larger quarters in Culver Hall, in space that had been recently vacated by the chemistry department. Here, the collection of prints and photographs could expand, along with the art library. In December 1927, Frank P. Carpenter of Manchester, New Hampshire, gave President Ernest Martin Hopkins funds to erect a building specifically for the art department. Carpenter Hall opened officially on June 14-18, 1929. The Guide to the Buildingand Special Exhibits published on that occasion noted:

Carpenter Hall provides a home for all the interests pertaining to the visual arts at Dartmouth. The building not only constitutes a complete teaching unit for the courses in Art and Archaeology, it also houses under one roof ... a wellequipped Art Library, a central collection of photographs and lantern slides, a considerable collection of prints and colored reproductions, galleries for rotating exhibits of special and general interest, an up-to-date public lecture hall, well-lighted studios for the convenience of those who like to draw, paint, or model, and rooms for group discussions . . . Only those familiar with the inadequacy and scattered nature of such facilities as have been hitherto available can appreciate the importance of this splendid addition to the equipment of the College.

To make it possible for the exhibition rooms to have skylights, the galleries were placed on the third floor of the building. In retrospect, it may have been this decision that prevented eventual expansion of the Carpenter galleries into a full-fledged art museum. Well out of the way of normal student traffic, not to mention that of faculty, alumni, and the general public, these elegant galleries never completely fulfilled their potential. But the art department had further plans for bringing art into the lives of the students. The Guide concluded with the following note:

Although no regular courses of instruction in the practice of drawing and painting are offered at present, facilites are provided for students who wish to pursue these interests as an extra-curricular activity. From time to time advice and criticism may be received from visiting professionals.

This modest statement was a harbinger of Dartmouth's renowned Artist-in-Residence tradition.

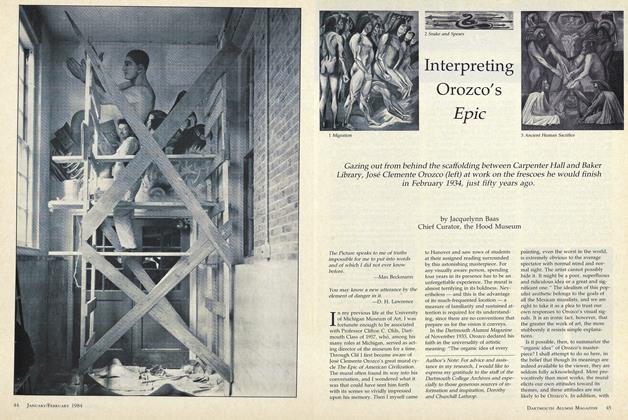

Carpenter Hall was completed during the depths of the Great Depression. However, it was not long before the chairman of the department, Artemas Packard, along with Churchill P. Lathrop, who had joined the department in the fall of 1928, were plotting to obtain the services of one of the great Mexican muralists to decorate their new building and provide students with a vivid example of work done in the Renaissance technique of fresco painting. Packard and Lathrop smoothed the way for their idea by installing Dartmouth's first Artist-in-Residence in the art studios on the top floor of Carpenter: Carlos Sanchez '23. They also used the Carpenter Art Galleries to hold several exhibitions of drawings and prints by Jose Clemente Orozco, the muralist they favored for Dartmouth.

Through the generosity of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and the enthusiasm of his wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (whose son Nelson was a member of the Dartmouth Class of 1930), Orozco was brought to Dartmouth in the spring of 1932. To the credit of Packard and Lathrop, and that of the College librarian, Nathaniel L. Goodrich, Orozco was encouraged to paint where he wished: not in Carpenter, but on the great expanse of plaster wall in the Reserve Corridor of Baker Library, directly adjacent to Carpenter. Orozco was given a faculty appointment by the Trustees, and for almost two years, Students were able to witness a great artist at work. The Epic of American Civilization, which was completed in February 1934, is arguably the finest mural in this country.

In 1935, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, an indefatigable patron of contemporary artists and a founder of the Museum of Modern Art, gave the College more than 100 paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures. The gift constituted Dartmouth's first important collection of modern art. In addition to numerous works from the modern period, the Rockefeller gift also included examples of nineteenth-century paintings and sculpture, and folk art.

This proved to be the beginning of a series of major gifts of works of art to the College, a phenomenon that was chiefly due to the efforts of one man: Churchill Pierce Lathrop. Appropriately, the Modern gallery in the new Hood Museum of Art has been named in his honor. Without "Jerry" Lathrop, many of the important works that led to the construction of the Hood Museum of Art would never have come to Dartmouth.

That same year, Ray Nash set up his influential Graphic Arts Print Shop in the basement of Baker Library. Associated with both the English and the art departments, Nash educated almost two generations of Dartmouth students in the history and art of graphic design and printing. Becauseof of his influence and the energetic collecting activities of Professor Lathrop, Dartmouth now boasts an extensive print collection.

Within three decades after the opening of Carpenter Hall, the Carpenter Art Galleries could no longer accommodate the College's expanding collection. A need had simultaneously arisen for a performing arts facility. The result was the Hopkins Center, where President Dickey envisioned that all the creative arts would be brought together under one roof for the purpose of mutual enrichment.

When the Hopkins Center opened in the fall of 1962, it contained new facilities not only for theater and music, but for the visual arts as well. Designed by Wallace K. Harrison, (who also designed New York's Metropolitan Opera House), the Hopkins Center housed the studio art program and provided additional gallery, storage, and preparation areas for an increasingly active program of special exhibitions. This time, however, the galleries were purposely placed in the mainstream of student life indeed students had to pass them to get to their mailboxes and to the Center's snack bar.

The improved visibility of art in the Hopkins Center galleries had dramatic consequences for the growth of the art collection and for the visual arts at Dartmouth in general. However, the migration of the gallery operation from Carpenter Hall had other effects as well. While the administration of the art galleries was incorporated into the activities of a lively performing arts center, the art history faculty and the art library remained in Carpenter. Inevitably, this administrative change resulted in a shift of emphasis away from the curricular concerns of scholars in the humanities and social sciences. And while Hopkins Center provided new storage space for the College's growing art collection, exhibition space for the permanent collection remained across campus in Carpenter Hall. (The Jaffe-Friede Gallery in Hopkins Center was used primarily for special exhibitions.) As a result, fragile works of art had to be transported back and forth across campus in all kinds of weather. The creation of the Hopkins Center Art Galleries also had unforeseen consequences for the rest of Dartmouth's museum collections. Works of ethnographic interest, which during an earlier era would have been incorporated into the anthropology collection in Wilson Hall, now tended to be given as art objects to the Hopkins Center Art Galleries. At the same time, curricular interest in the College Museum's natural history collection had virtually disappeared.

When an economic recession threatened College resources during the early 1970s, the administration initiated an evaluation of museum and gallery operations at Dartmouth. In late 1974, it was decided that the College should divest itself of its natural history collection. Early the following year, an agreement was reached with Dr. Robert Chaffee, director of the College Museum, allowing him to take the College's natural history collection and found a regional museum in the Hanover area: the now-thriving Montshire Museum of Science. Even so, the remaining operations of the College's museum and galleries remained widely scattered. Five exhibition and three storage areas were in three sep- arate buildings. And the museum offices and work space were divided between Wilson Hall and Hopkins Center. Obviously, the College needed a new facility.

In 1976 the College initiated a major Campaign for the Arts at Dartmouth as part of the Campaign for Dartmouth. At that time, Peter Smith, then the director of the Hopkins Center, effectively stated the challenge that faced the College:

Dartmouth lacks the one thing that would give to the study and display of the fine arts what the Hopkins Center has so conspicuously given to the performing arts and the Visual Studies program space commensurate with achievement and need, and a focus for increased attention. Until a new center is built devoted to the exhibition and contemplation of works of art, Dartmouth will not be able adequately to teach its students the kind of connoisseurship and visual discrimination which can make the crucial difference for artist and art historian alike, as well as for the future patron, collector, critic, trustee or curator. . . In addition to the effect on visual education at Dartmouth, a new museum would immediately become, as the Hopkins Center has, a great regional resource, affecting the much broader community beyond the College. And such museums consistently attract generous new gifts of art.

The funding to meet this goal was assured in 1978, when the College received a bequest for a "major educational facility" from Harvey P. Hood '18, a Trustee from 1941 to 1967. Harvey Hood had been an adviser to two Dartmouth presidents: Ernest Martin Hopkins '01, for whom the Hopkins Center is named, and his successor, John Sloan Dickey '29, who was largely responsible for the concept of the Hopkins Center as a meeting place for all the arts. This major bequest was augmented by additional gifts from members of the Hood family and from other generous supporters of the arts at Dartmouth.

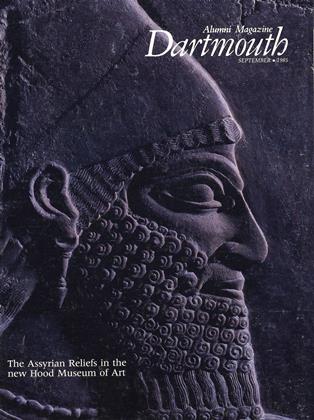

On September 27, 1985, the new Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College will be dedicated.

The galleries in Carpenter Hall have been transformed into classrooms for the departments of art history and anthropology. (There is a decorous symmetry in the fact that the anthropologists have joined the art historians there, just as the former anthropology collection has joined the art collection in the new Hood.)

The Hood Museum will be an independent entity, free to develop the resources necessary to serve its diverse audience of students, scholars, and the general public. Yet the Hood also retains important physical links to the Hopkins Center, where its former exhibition galleries acquire new uses in the service of students and faculty in Dartmouth's visual studies department.

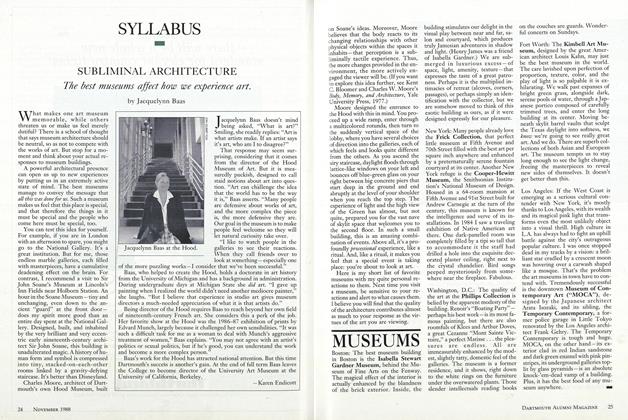

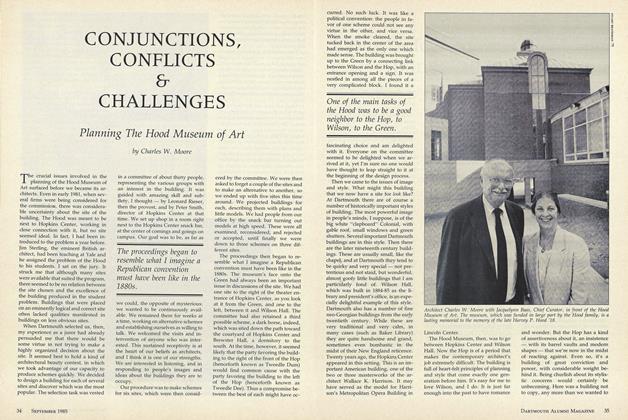

Architect Charles Moore's familiarity with the academic environment, combined with his responsiveness to traditional forms, made him the perfect choice for Dartmouth's new museum. In the essay that precedes (pp. 30-32), Moore recalls the active involvement of the College community in the building's planning and the crucial decisions behind its design. Above all, the Hood Museum of Art was intended to serve as a "good neighbor" within Dartmouth's varied architectural setting. This is especially fitting for a collection whose history is so richly interwoven with that of the College itself.

The Berlin Painter, Greek. Panathenaic Amphora, c. 500-475 B.C. Terra-cotta.Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ray Winfield Smith,Class of 1918.

Attributed to Thomas V. Brooks,American. Baseball Player (ShopSign), c. 1870-75. Polychromed wood.Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

Attributed to Lavinia Fontanel, Italian. Portrait of a Lady as Astronomy, c. 1585. Oilon canvas. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. M. R. Schweitzer.

Edward Ruscha, American. Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, 1963. Oil on canvasGift of James J. Meeker in memory of Lee English, Class of 1958.

Mark Rothko, American. Orange and Lilac over Ivory, 1953. Oil on canvas. Gift ofWilliam S. Rubin.

Paul Revere II,American. Water Pitcher, 1804.Silver. Gift ofLouise C. andFrank L. Harrington, Class of1924.

William Merritt Chase, American. The Lone Fisherman, 1890s. Oil on panel.Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Preston Harrison.

Regis François Gignoux, French. New Hampshire (White Mountain Landscape), c. 1864. Oil on canvas. Purchase made possible by a gift from Olivia H.and John O. Parker, Class of 1958, and the Whittier Fund.

New Mexico, Acoma Pueblo. Water Jar, c. 1900. Terra-cotta with pigment.Bequest of Frank C. and Clara G.Churchill.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, American. Maud in Bed, 1884-86. Watercolor,gouache, and pencil on cardboard. Gift ofMr. and Mrs. Arthur E. Allen, Jr., Classof 1932.

Minnesota, Ojibway. Bandolier, c.1900. Glass trade beads, cotton clothfoundation and lining, silk trim. Bequestof Frank C. and Clara G. Churchill.

Luca Giordano, Italian. The Martydom of St. Lawrence, c. 1696. Oil on canvas. Gift ofJulia and Richard H. Rush, Class of 1937.

Master of the Bambino Vispo (probably Gherardo Stamina,Italian.) Death of the Virgin, c. 1405-10. Tempera onpanel. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ray Winfield Smith, Class of1918.

John Singleton Copley, American. Portrait of Governor John Wentworth, 1769. Pastel onpaper mounted on canvas. Gift of Esther LowellAbbott, in memory of her husband, GordonAbbott.

Pablo Picasso, Spanish. Guitar on a Table, 1912. Oil,sand, and charcoal on canvas. Gift of Nelson A.Rockefeller, Class of 1930.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, English. The Sculpture Garden, 1874Oil on canvas. Gift of Arthur M. Loew, Class of 1921A.

The Hood Museum of Art Dedication Week Sept. 23 11 am Convocation, with an address by Frank Stella (ThompsonArena) Sept. 26 4pm Lecture by Paul Goldberger, architecture critic, NewYork Times Spaulding Auditorium, tickets required) Sept. 27 1:30 pm Museum dedication 8:00 pm Lecture by Charles W. Moore, architect (Spaulding Auditorium, tickets required) Sept. 28 9-5 pm Tours for the general public 8:30 pm Film, "Dartmouth in Hollywood," celebrating alumni contributions to the art and commerce of film (Loew Auditorium, tickets required). Sept. 29 9-5 pm Tours for general public

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCONJUNCTIONS, CONFLICTS & CHALLENGES

September 1985 By Charles W. Moore -

Feature

FeatureJourney's End: The Assyrian Reliefs at Dartmouth

September 1985 By Judith Lerner -

Feature

FeatureDingwall of Dartmouth

September 1985 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

September 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsMany Sighs and Many Tears

September 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

ArticleThe Life of the Mind

September 1985 By Dorothy Foley '86

Jacquelynn Baas

Features

-

Feature

Feature1940 Improvement Over 1939

April 1941 -

Feature

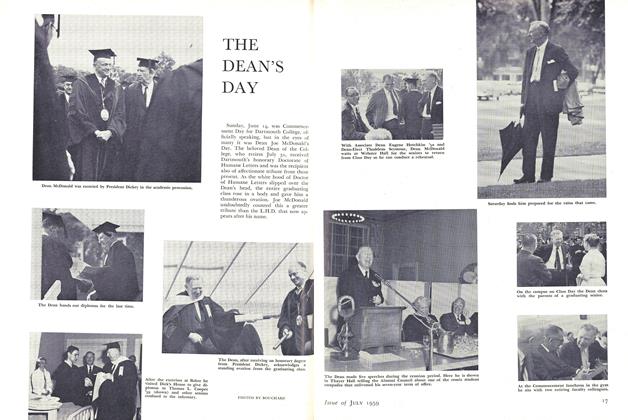

FeatureTHE DEAN'S DAY

JULY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureO Pioneers

June 1974 -

Feature

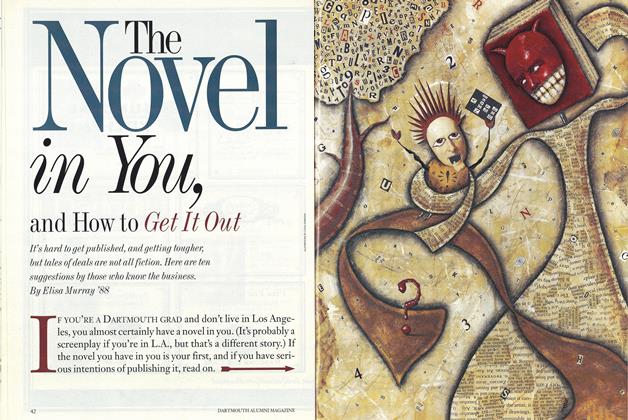

FeatureThe Novel in You, and How to Get It Out

DECEMBER 1996 By Elisa Murray '88 -

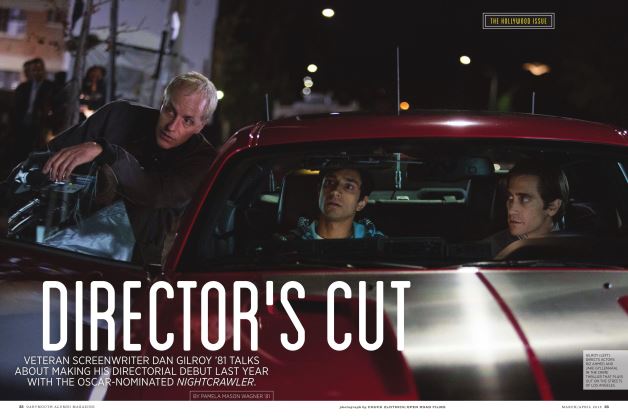

FEATURE

FEATUREDirector’s Cut

MARCH | APRIL By PAMELA MASON WAGNER ’81 -

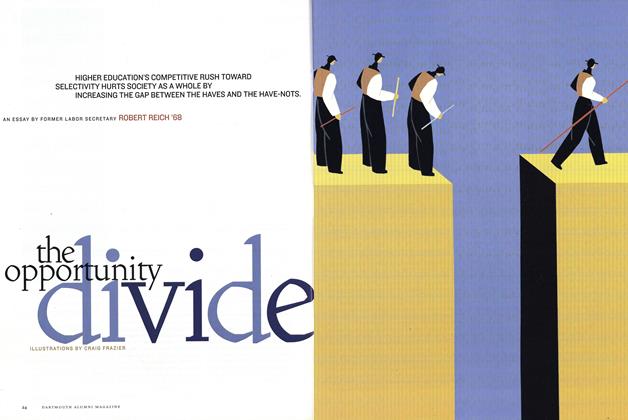

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Opportunity Divide

Mar/Apr 2001 By ROBERT REICH ’68