"They hate Henry Adams," confided Mary Kelley. She had given a rousing lecture on the autobiography of Henry Adams before 58 of this country's corporate elect (plus one from Newfoundland), and many of her audience had found Adams irritating. The question period was a sizzler.

"This is a book by a loser about a loser," insisted one executive. "Adams was a man who needed a job" Kelley, a member of Dartmouth's history faculty, pointed out that though Adams was privileged, he was also an historian, for whom observing and speculating was work, hard work.

"I'm troubled," said her next questioner, "by Adams's calling the twelfth century unified and the twentieth century chaotic. What is complexity to a participant is chaos to a dilettante!" It can be useful, offered Kelley, for someone to suggest occasionally that there may be forces we cannot control.

It was an ordinary session at the Dartmouth Institute the month-long program of continuing education mounted every summer by the College. The Institute, founded in 1972 as one of the first acts of his presidency, was the brainchild of John Kemeny.1 The new president felt strongly that

the College's commitment to continuing education should be extended beyond the confines of its own alumni body:2 "It is highly desirable for those in business and the professions, especially those concerned with matters of policy, to return occasionally to a college or university campus for periods of intellectual refreshment and mindstretching."3 It was Kemeny's feeling that the worlds of business and academe had a lot to say to each other4 and that Dartmouth was a good place for it to get said.

The program-a crash course in liberal arts for corporate middle management5 has a reputation as "an intellectual and emotional experience of rare intensity and richness."6 Some of the country's largest corporations among them AT&T, IBM, Texaco, Ford, GE, I. Magnin, and the IRS -send their most promising executives to Hanover for a four-week sabbatical during which they live in dormitories, read and discuss an impressive set of books, listen to highpowered lectures presenting the very latest in the liberal arts, keep daily journals about their intellectual experiences, and interact socially with one another and six members of Dartmouth's tenured faculty.

In 1984, the companies paid $6,300 per participant. If they heeded the urgings of the Institute, they also sent spouses, who come as full and equal participants but cost less- $3,300 each. The educational background of participants ranges from high school diploma to one or more graduate degrees, and the age range to date has been 29 to 63.7 Every year at least one new company turns up. Gilbert Tanis '3B directed the Institute for its first 12 years, until 1983, when he retired and turned the class of 1984 over to a new director, Thea Froling.

Case-study professional institutes such as the one offered by the Harvard School of Business abound in this country, but there are only a few liberal arts programs like the Dartmouth Institute. Taking time away from the ledger to refurbish the intellect is not yet regarded as something American business people normally do. One such program is offered by Wabash College in Indiana, another by Stanford University in California, and a third by Washington and Lee in Virginia. The five-week "American Studies for Executives" course at Williams College in Massachusetts is the oldest of the nation's five college-sponsored liberal arts programs for executives, and Dartmouth's is the largest8 and the only one that invites spouses as full participants. "The granddaddy of them all," explains Tanis, "isn't run by any college. It's the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies, a two-week course at Aspen Meadows in the Rockies offered by Robert Anderson of Atlantic Richfield."

Not all of the 103 companies that have participated in the Dartmouth Institute are American. Sweden, Germany, Canada, Italy, Spain, and Panama have all sent executives to Hanover according to Froling, who says she would "like to increase foreign participation the Institute is a wonderful introduction to America for multinational executives." Froling's comment reflects the fact that "America," one of the three courses that make up the Institute's academic program, is a detailed examination of this country's history and culture.

The other two courses taught at the Dartmouth Institute are "Culture and Perspective," which ranges the globe geographically and historically, and "Science," which grapples head-on with such puzzlers as creation, evolution, nuclear physics, relativity, and quantum mechanics. The reading list is hefty and firmly insisted upon. "Without that demand, the whole intellectual milieu would be destroyed," explains Institute professor Louis Renza of Dartmouth's English department. "Tennis is not what the Dartmouth Institute is about."

Among the works this year's participants read were a history of West Africa from A.D. 1000 to 1800; part of Das Kapital; novels by Vonnegut, Fitzgerald, Conrad, Pynchon, and Zola; Geological Survey Professional Paper 669-A; three of Emerson's essays; a scientific biography of Einstein; Women's America; Robert Jastrow's RedGiants and White Dzvarfs; and Zen andthe Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Films seen by the participants included a Berthold Brecht production, a Third Reich propaganda film, one about Hiroshima, a documentary about a women's bank strike, and Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now. And there was discussion about medieval France and Baghdad, about evolution and the second law of thermodynamics, about Corot and Monet and tachyons, the Women's Movement, the Big Bang theory, nuclear disarmament, conservationism, Hollywood, and how atom bombs are made.

It is a stimulating agenda, and what Froling refers to as "the tremendously exciting chemistry between the academic and corporate worlds at their best" sometimes gets explosive. "We address those areas traditional management programs don't," explains Froling, "such as creativity in leadership, breadth of vision, enhanced judgment." "Liberating" those qualities in highly successful corporation executives who have put in years of overtime focused on the bottom line often necessitates the busting up of some complacencies and habits of short sight. The faculty approach their task with a mixture of gusto and fear and trembling.

As Institute professor Charles Drake of Dartmouth's earth sciences department explains, "I begin by pointing out that two billion years ago in Gabon, Africa, nature had a natural reactor that went critical and delivered 15,000 megawatt hours of energy. That equals the output of a large nuclear power plant operating for five years. Nature did that. We're not so damned smart. And Los Alamos, I tell them, sits on the flank of the Valles Caldera — one of the three largest explosive volcanoes in the United States." The faculty take care, Drake says, not to be controversial for the sheer sake of controversy, but in only one month, there is not a lot of time for pussyfooting. "My stuff geology is not very controversial. It doesn't really run contrary to the models already in their heads. That's true with De Mook's physics, too; but Lou Renza, Mary Kelley, Steve Nichols the humanists heap on models that the participants are not used to. And they have to lay a lot on them in a short time a hundred years of women's history, for instance, in one and a half hours. That gets hard to accept sometimes."

We're teaching a kind of plurality" is the way Renza sees the faculty's task. "It is not necessary for us to contradict their world just to point out that it is only one part of the American world." It's difficult, says Drake, to let go of something lived as intensely as most of the participants live their careers but stepping back from business, if not letting go of it, is what the Institute is all about.

The return the corporations expect for their investment, according to Renza, is revitalization. Drake recalls a discussion he once had with Institute proponent Ralph Lazarus '35, former Dartmouth Trustee and corporate director of Federated Department Stores. Lazarus talked to Drake about the frequency with which he encounters executives who, because they are good, have become so immersed in their businesses that they have lost perspective. They don't see the rest of the world, Lazarus told Drake, and we need broad vision at the top.

Some participants seek the opportunity to come, says Drake, and others are sent kicking and screaming. Most but not all are won over by the end of the four weeks. Early in the program, there is a lot of perplexity and irritation expressed at coffee breaks. "I didn't get anything out of it today" you will hear, and "It solved nothing!" One of the most frequent complaints concerns the unwillingness of the faculty to explain to the participants how to link what they are learning at the Institute with their businesses. "We can't give them a bottom line, tell them how to apply what we teach them to business or to life," explains Institute professor Stephen Nichols, who chairs Dartmouth's French and Italian department. "Look at the theory, I keep saying. There is more theory in what you are doing than you think. Just seeing that can lead to doing away with short-term imperatives in business decisions that can take you right down the tubes."

Sometimes, however, there is real pain in the process. "I had a sense of order at the beginning," cried one executive. "Now I am in disarray. Am I supposed to let art turn this disorder into order? Or to cultivate disorder itself?" This cri de coeur was addressed to Institute professor Delo Mook of the College's physics and astronomy department, who had just demonstrated the impossibility of predicting with any certainty at all where any given particle in the universe will be at any given time. Mook's reply was compassionate but firm: "Things are not as orderly as we thought they were. I'm sorry. That's the way the world is."

The unsettling emotions that accompany mind-stretching afflict the faculty as well as the participants. The six professors two from the humanities, two from the social sciences, and two from the sciences commit themselves to a joint venture when they agree to teach in the Dartmouth Institute. Paired along divisional lines in a "buddy" system, they start preparing for the next Institute a month after the previous session ends. In the fall, there is an overnight planning retreat, after which the pairs continue to meet, refining and meshing reading lists and lectures. At a longer retreat in the spring, all six go through a dry run of the entire course. "It's exhausting," explains Renza. "We actually deliver 15-minute synopses of each lecture so we can establish relationships among them all. We create a provisional calendar, screen films, tear down things that don't work, and rebuild until it all fits."

Because this Institute is uniquely dedicated to the development of a close-knit intellectual community, its faculty do not as they do in other such programs come in to lecture and then disappear until their own next lectures. All faculty attend all sessions of the Dartmouth Institute, including meals and social events. As Drake explains, "We are as much students as the participants. I listen to Steve, Lou, Mary and I'm no more expert at what they're talking about than any of the participants. That's the strength of the program. It's a genuine searching together."

The 1984 session was Renza's first year teaching at the Institute, and he was surprised, he says, at just how cooperative the faculty were. He found the experience professionally challenging: "You have to strain to get over to the other disciplines. Their methodological approaches are so different from yours that you have to leap to understand them, and that stretches you." The effect of all this professional humility is beneficially shocking to the participants, says Nichols: "It blows their minds that we're at everyone else's lectures and taking notes."

Another sort of stretching comes from the way the mystique of the professor gets broken down during the course of the Institute. For many of the faculty, the confronting of an adult student body has its come uppances. "Undergraduates have to listen to you," says Renza, "and you have an automatic authority in their eyes. You can intimidate the Institute participants a little on the strength of your discipline, but in terms of their confidence in themselves and in their senses of right and wrong, you are going to find that their ideas are as powerful as your own, if not more so. And the fact of socializing with them means you are among them. They don't come up to you sycophantically, but as if you are one of them. I had to go through that demystification."

Institute professor Hoyt Alverson of the College's Department of Anthropology attributes much of the success of the Institute to just this departure from the academic tradition that puts students at the feet of masters with answers. "The ideal of a liberal education, we normally argue, is to be had only by students," he explains. "The faculty teach their separate disciplines and the students put everything together. At the Institute, we faculty do that. Synthesis and rapprochement are begun among the faculty as we reach out from our various disciplines to make contact with one another's, and the participants are then invited to bring their experience to the task. They watch us grapple, and then they get in there and grapple too." Ideally, says Alverson, all this trotting back and forth across professional borders generates a recombinant mixture of ideas that can lead to new ways of thinking about problems old and new.

So everybody stretches together and on both sides of the lectern there is often a sense of having become "a different person" because of it.

One of the early participants, Robert F. Murphy, then president for the overseas operations of General Motors Acceptance Corporation, discovered a new side of himself at Dartmouth. "I never thought I'd find myself getting up two hours before breakfast to read Conant and Whitehead, or Dostoyevsky and Freud, but that's what I've been doing and liking it," he told an interviewer.9 The Institute brochure quotes a similarly enthusiastic Thomas Malone, deputy director of the National Institutes of Health, who attended in 1974: "The Dartmouth Institute has for me, through an extraordinarily effective program of instruction, brought unification of the liberal arts with the physical and life sciences. Every problem I face and every decision I make is now seen through the window of this more global perspective."

William Grabe, president of IBM's national accounts division, is said to have described his Institute experience as "the most meaningful thing I've done in my adult life." Grabe was particularly enthusiastic about his wife's participation: "It was the first time we had had a chance to get away, to talk about things other than the house and children and what we would do on the weekend. Instead, we were sharing an intellectually stimulating experience, looking at great philosophers and the problems of mankind, ideas we would never normally discuss. We are better people, and we have a better marriage for having done this."10

That last sentiment is one the Dartmouth Institute staff hear often. "I met my wife for the first time at Dartmouth. It was a side of her I had never seen before,"11 is the way one participant put it, and Froling recalls being told by another, "It was the most important intellectual experience of my adult life and the most wonderful four weeks with my wife since our honeymoon."

Astronomer Mook, who served the Institute for eight years as academic director, also speaks movingly about how much it has meant to him to teach at the Institute. He has learned, he explains, a tremendous amount about American business, and the experience has had a profound effect on his regular teaching. Looking up suddenly, he adds with a seraphic smile, "We do change people, you know."

1. Eleanor Berman, "Corporate Colleagians," American Way (February 1984),P. 136. 2. Mary Ross, "Dartmouth Inatitute Plans First Session," Dartmouth Alumni Magazine (March 1972), P.26 3. John Kemeny, quoted in robert Graham, "Verdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK," Dartmouth Alumni Magazine (October 1972), P. 22. 4. Thea Froling, director, Dartmouth Institute, quoted in Berman, quoted in Berman, P. 136.

5. Berman, p. 134. 6. Graham, p. 21. 7. 1985 Dartmouth Institute brochure. 8. Berman, p. 134.

9. Graham, p. 22. 10. Berman, p. 136. 11. Ibid.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StorySenator Paul Tsongas '62 Heading Home from Washington

January | February 1985 By Douglas Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeaturePutting the Treasure at Risk

January | February 1985 By John S. Dickey, Jr. '63 -

Feature

FeatureThe "Greening" of the NFL

January | February 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Sports

SportsSports

January | February 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

Article"No Such Thing as Can't"

January | February 1985 By Frank Cicero '85 -

Article

ArticleJohannes von Trapp '63: A Man of the World in the Hills of Vermont

January | February 1985 By Doug Greenwood '66

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

MARCH 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

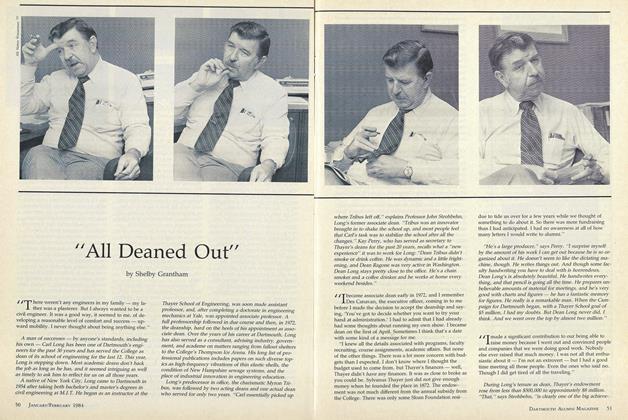

Feature"All Deaned Out"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

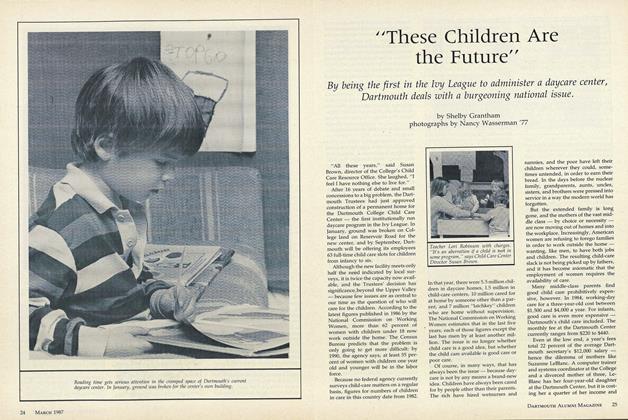

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

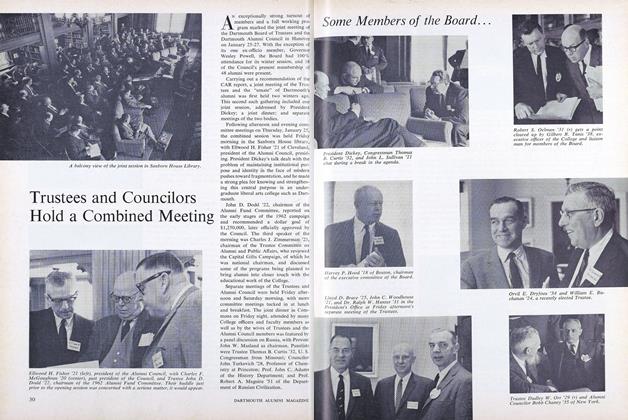

FeatureSome Members of the Board...

March 1962 -

Feature

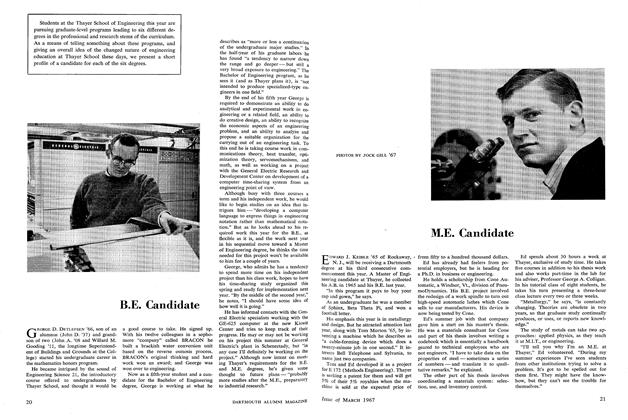

FeatureME Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs "The College" a College?

December 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureThe New Breed of Engineer

MARCH 1967 By MYRON TRIBUS -

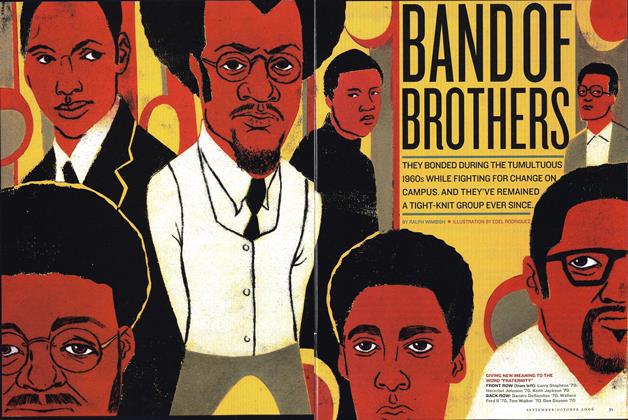

Feature

FeatureBand of Brothers

Sept/Oct 2006 By RALPH WIMBISH -

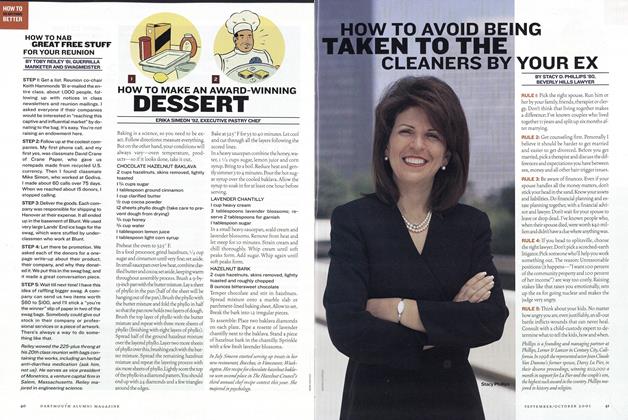

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO NAB GREAT FREE STUFF FOR YOUR REUNION

Sept/Oct 2001 By TOBY REILEY '81