I've been told that, in every liberal arts education, there will be one course, one professor, or just one academic experience that will affect a student so deeply as to bring his or her whole body of learning into perspective. The experience connects an education's worth of disparate liberal arts subjects and it is also (I hope) the most fond memory recalled when the student becomes an alum.

Ironically, in my case this crucial, perspective-setting instrument was a course intended to "introduce" students to the institution they already know best: the American school. "Educational Issues in Contemporary Society," which I took in the fall of my senior year, challenged almost every aspect of education (including my own) as I knew it. This made me rather uncomfortable at first. But familiarity wasn't the aim of Ed 20.

I had tended previously to define liberal arts in terms of special courses or professors the biology prof, for example, who prepared a personalized final exam for me and for each of the 70 other students in his class. Though my memory of plant reproduction may fade a bit over the years, I will never forget that professor.

Ed 20 taught me something else: one professor an education does not make. The course introduced me to a new approach, a new and important way of thinking, that caused a sort of geological event in my education. My previous courses and professors shifted slightly and were realigned along a different line of perspective. Because of Ed 20, I will use them differently, and my previous experience is all the richer.

In a typical Ed 20 class, Professor Andrew Garrod (who insists, like all the other professors in the Education Department, on being called by his first name), dressed smartly in corduroy pants, V-necked sweater and tweed blazer, walks around in front of the classroom as if he is conducting an orchestra of 60 or so. In a clipped English accent, he cites a study done by a respected scholar that purports to prove that males dominate classroom discussions. "It is obvious, really," he says with obvious intent to provoke. "Males speak up more often, and teachers tend to call on them more often than on females."

"The study doesn't prove anything," challenges a male student in a loud and emotional tone. His dissenting voice heard frequently in class is a fresh point of view for me.

"Well, at my school. . begins the guy at the end of my row. Everyone laughs. He is active in class discussions. I know so much about his experiences by now that I feel as if I went to school with him. But Professor Garrod sorry, Andrew encourages these personal accounts. He interjects, as he does often, "How do you feel about this?" Most of his questions, though, are aimed at the "why's" behind our stories.

The debate goes on for ten minutes or so until a student who has never spoken in class before raises her hand. Andrew calls her by name even though she has never met him in or out of class. The woman says she has been keeping track of the participants in the discussion that day and has found it to have been dominated by women.

"Okay/' offers Andrew, "why do you think that is?" And the forum is underway again.

Outside the classroom, the course gets more unusual. There are no deadlines or due dates; students are free to work, or put off work, at their own pace. Course requirements consist of four writing exercises designed to teach students how to write a "concise, well-crafted argument," and four oral reading checks to encourage students to read, understand, and relate to each other and to personal experience articles about education today. The point of these exercises is self-examination and independent activity; the course allows for maximum creativity and the incorporation of personal experiences and beliefs.

Everything in Ed 20 even the structure and requirements of the course itself was open to criticism and was, inevitably, challenged by members of the class. We grappled with definitions and meanings illiteracy, moral education, teacher excellence and tried to determine what the discrepancies in our different interpretations meant to society. In short, nothing was ever laid down as law in Ed 20. This is rare at Dartmouth, at least among the courses I have taken, and I wasn't completely prepared for it.

I guess politics had something to do with my surprise. Ed 20 is guided by a liberal bias, at times subtle and at other times quite blatant. This seemed to turn some students off, but for me it was a breath of fresh air. I have been in private school since age 12, and I consider myself a conservative student in many ways. I had never before been encouraged to question socialization or any other force that shapes the learner in school. So, while Ed 20's aspirations were considered rhetorical and idealistic by some students, for me they were new and inspiring.

Ed 20 did not change my political views, but it certainly did have some important personal .'effects. Now I am more likely to challenge beliefs, including my own. I find "truth" a much more ephemeral goal; and now the search for it is, strangely, that much more enjoyable. I feel the-need to dig deeper in and out of my studies, and to begin questioning things I have always taken for granted. The new perspective I have gained is a direct result of Ed 20, a course one could find only at a liberal arts school.

Of course, I am not the first to enjoy this senior-year epiphany. In June 1930, a Dartmouth student wrote in this magazine about an experience that similarly changed his outlook. In his case, it was his Senior Fellowship, which awoke in him a passion for the arts. "I have discovered the key to the door which opens out into a field totally unrelated to the material side of life," he reported. "And now it is up to me to unlock this door and explore the ground lying beyond."

The student went on to a career in public life, but his interest in the arts intensified over the years and led him to become one of the world's leading collectors. For this student, a young man named Nelson Rockefeller, the liberal arts at Dartmouth clearly did its work.

Lesley Barnes is an English major and an internwith this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

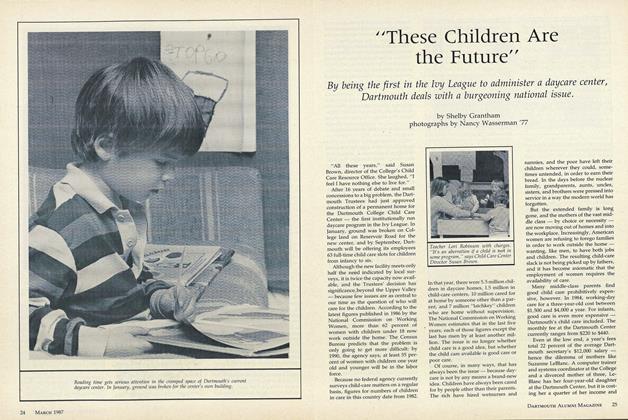

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

March 1987 By Shelby Grantham -

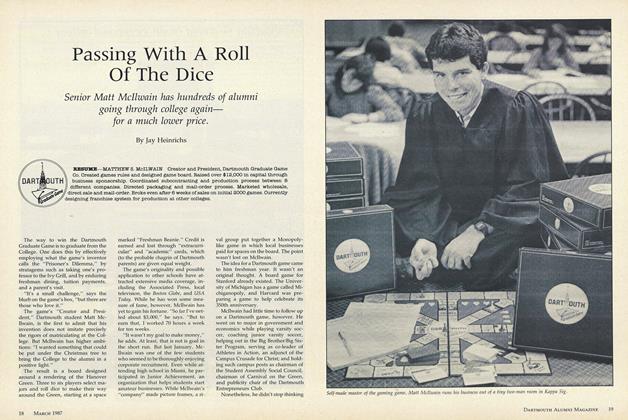

Cover Story

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

March 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

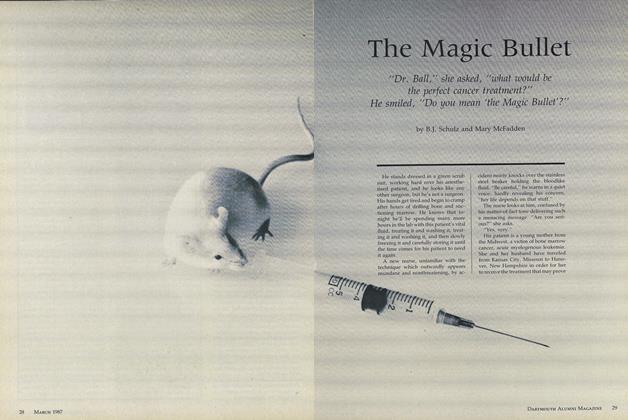

FeatureThe Magic Bullet

March 1987 By B.J. Schulz arid Mary McFadden -

Feature

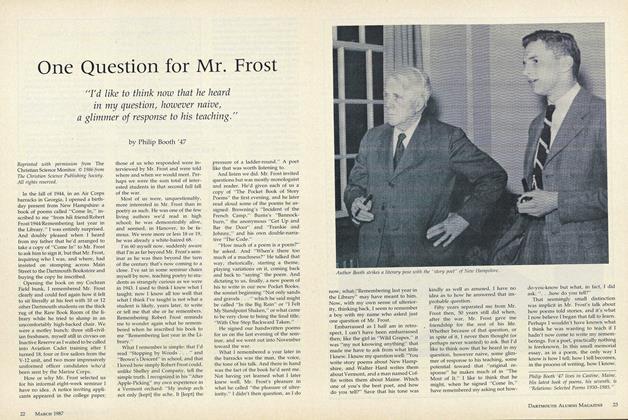

FeatureOne Question for Mr. Frost

March 1987 By Philip Booth '47 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

March 1987 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

March 1987 By Ken Johnson

Lesley Barnes '87

Article

-

Article

ArticleINSTRUCTION IN WRESTLING AND BOXING

January 1917 -

Article

ArticleWar Bonds

May 1942 -

Article

ArticleWith the Facuty

November 1949 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Publications

July 1951 -

Article

ArticleInn Greeters With a Window on the Green

December 1975 By DAVID SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleSarasota

FEBRUARY 1968 By GILBERT H. ROBINSON '26