"I'd like to think now that he heard in my question, however naive, a glimmer of response to his teaching."

Reprinted with permission from The Christian Science Monitor. © 1986 fromThe Christian Science Publishing Society.All rights reserved.

In the fall of 1944, in an Air Corps barracks in Georgia, I opened a birthday present from New Hampshire: a book of poems called "Come In," inscribed to me "from his friend/Robert Frost/1944/ Remembering last year in the Library." I was entirely surprised. And doubly pleased when I heard from my father that he'd arranged to take a copy of "Come In" to Mr. Frost to ask him to sign it, but that Mr. Frost, inquiring who I was, and where, had insisted on stomping across Main Street to the Dartmouth Bookstore and buying the copy he inscribed.

Opening the book on my Cochran Field bunk, I remembered Mr. Frost clearly and could feel again how it felt to sit literally at his feet with 10 or 12 other Dartmouth students on the thick rug of the Rare Book Room of the library while he tried to slump in an uncomfortably high-backed chair. We were a motley bunch: three still-civilian freshmen, myself still in civvies on Inactive Reserve as I waited to be called into Aviation Cadet training after I turned 18; four or five sailors from the V-12 unit, and two more impressively uniformed officer candidates who'd been sent by the Marine Corps.

How or why Mr. Frost selected us for his informal eight-week seminar I have no idea. A notice inviting applicants appeared in the college paper; those of us who responded were interviewed by Mr. Frost and were told where and when we would meet. Perhaps we were the sum total of interested students in that second full fall of the war.

Most of us were, unquestionably, more interested in Mr. Frost than in poetry as such. He was one of the few living authors we'd read in high school; he was demonstrably alive, and seemed, in Hanover, to be famous. We were more or less 18 or 19, he was already a white-haired 68.

I'm 60 myself now, suddenly aware that I'm as far beyond Mr. Frost's seminar as he was then beyond the turn of the century that's now coming to a close. I've sat in some seminar chairs myself by now, teaching poetry to students as strangely curious as we were in 1943. I used to think I knew what I taught; now I know all too well that what I think I've taught is not what a student is likely, years later, to write or tell me that she or he remembers. Remembering Robert Frost reminds me to wonder again what he remembered when he inscribed his book to me "Remembering last year in the Library."

What I remember is simple: that I'd read "Stopping by Woods ..." and "Brown's Descent" in school, and that I loved how simply Robert Frost could, unlike Shelley and Company, tell the simple truth. I recognized in his "After Apple-Picking" my own experience in a Vermont orchard: "My instep arch not only [kept] the ache, It [kept] the pressure of a ladder-round." A poet like that was worth listening to.

And listen we did. Mr. Frost invited questions but was mostly monologuist and reader. He'd given each of us a copy of "The Pocket Book of Story Poems" the first evening, and he later read aloud some of the poems he assigned: Browning's "Incident of the French Camp," Burns's "Bannockburn," the anonymous "Get Up and Bar the Door" and "Frankie and Johnny," and his own double-narrative "The Code."

"How much of a poem is a poem?" he asked. And "When's there too much of a muchness?" He talked that way, rhetorically, starting a theme, playing variations on it, coming back and back to "saying" the poem. And dictating to us, finally, a new poem of his to write in our new Pocket Books, the sonnet beginning "Not only sands and gravels ..." which he said might be called "In the Big Rain" or "I Felt My Standpoint Shaken," or what came to be very close to being the final title, "With One Step Backward Taken."

He signed our handwritten poems for us on the last evening of the seminar, and we went out into November toward the war.

What I remembered a year later in the barracks was the man, the voice, the tone of his talk. And there in hand was the fact of the book he'd sent me. Not having yet learned what I later knew well, Mr. Frost's pleasure in what he called "the pleasure of ulteriorly," I didn't then question, as I do now, what "Remembering last year in the Library" may have meant to him. Now, with my own sense of ulteriority, thinking back, I seem to remember a boy with my name who asked just one question of Mr. Frost.

Embarrassed as I half am in retrospect, I can't have been embarrassed then; like the girl in "Wild Grapes," it was "my not knowing anything" that made me have to ask from what little I knew. I know my question well: "You write story poems about New Hampshire, and Walter Hard writes them about Vermont, and a man named Coffin writes them about Maine. Which one of you's the best poet, and how do you tell?" Save that his tone was kindly as well as amused, I have no idea as to how he answered that improbable question.

Fifty years separated me from Mr. Frost then, 50 years still did when, after the war, Mr. Frost gave me friendship for the rest of his life. Whether because of that question, or in spite of it, I never then thought (or perhaps never wanted) to ask. But I'd like to think now that he heard in my question, however naive, some glimmer of response to his teaching, sompotential toward that ' original res ponse" he makes much of in "The Most of It." I like to think that he might, when he signed "Come In, have remembered my asking not how do-you-know but what, in fact, I did ask: ". . .how do you tell?"

That seemingly small distinction was implicit in Mr. Frost's talk about how poems told stories, and it's what I now believe I began that fall to learn. Perhaps I wouldn't have known what I think he was wanting to teach if I hadn't now come to write my rememberings. For a poet, practically nothing is foreknown. In this small memorial essay, as in a poem, the only way I know is how I tell; how I tell becomes, in the process of writing, how I know.

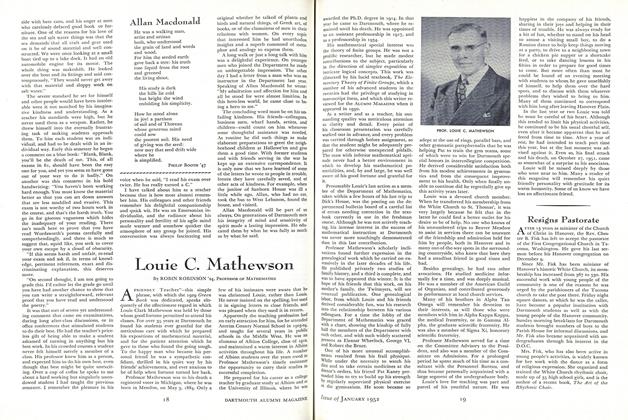

Author Booth strikes a literary pose. with the "story poet of New Hampshire

Philip Booth '47 lives in Castine, Maine.His latest book of poems, his seventh, is"Relations: Selected Poems 1950-1985."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

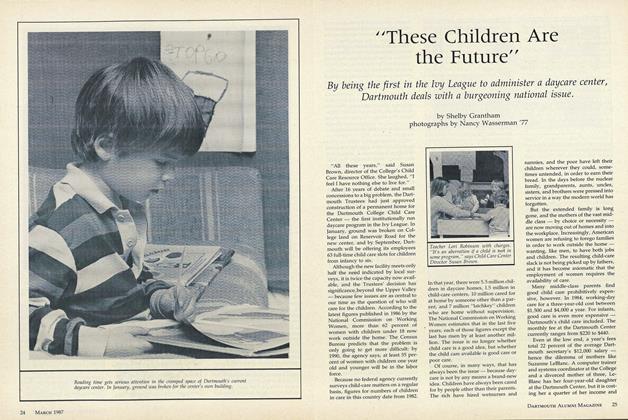

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

March 1987 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

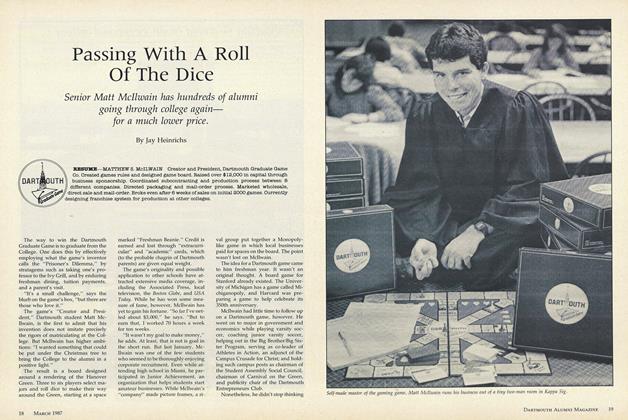

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

March 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe Magic Bullet

March 1987 By B.J. Schulz arid Mary McFadden -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

March 1987 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

March 1987 By Ken Johnson -

Article

ArticleSenior Epiphany

March 1987 By Lesley Barnes '87

Philip Booth '47

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

March 1957 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1976 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorMind and Matters

NOVEMBER 1999 -

Article

ArticleAllan Macdonald

January 1952 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Article

ArticlePreoccupation: Poetry

MARCH 1959 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Article

ArticleThe Islanders

MARCH 1963 By PHILIP BOOTH '47

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureCapitol Steps

May/June 2006 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

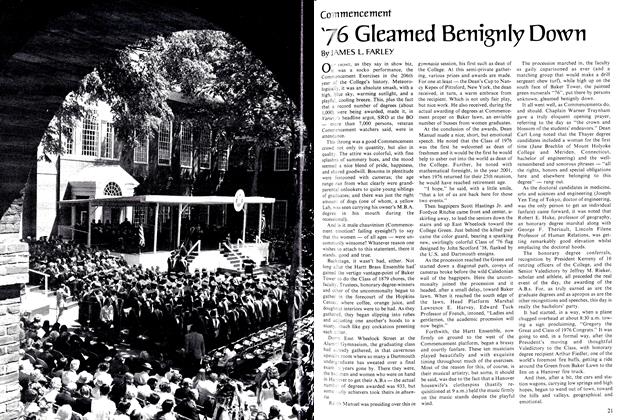

FeatureCommencement

June 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

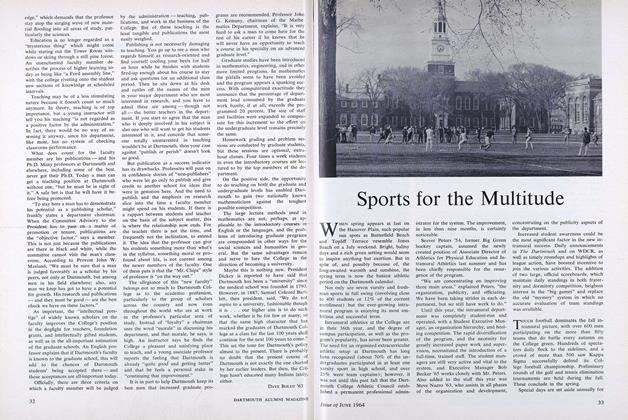

FeatureSports for the Multitude

JUNE 1964 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Feature

Feature"They Game from America and They Were Four"

December 1954 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

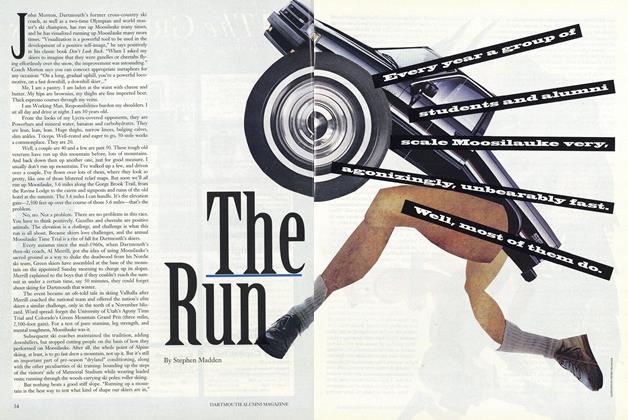

FeatureThe Run

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Stephen Madden