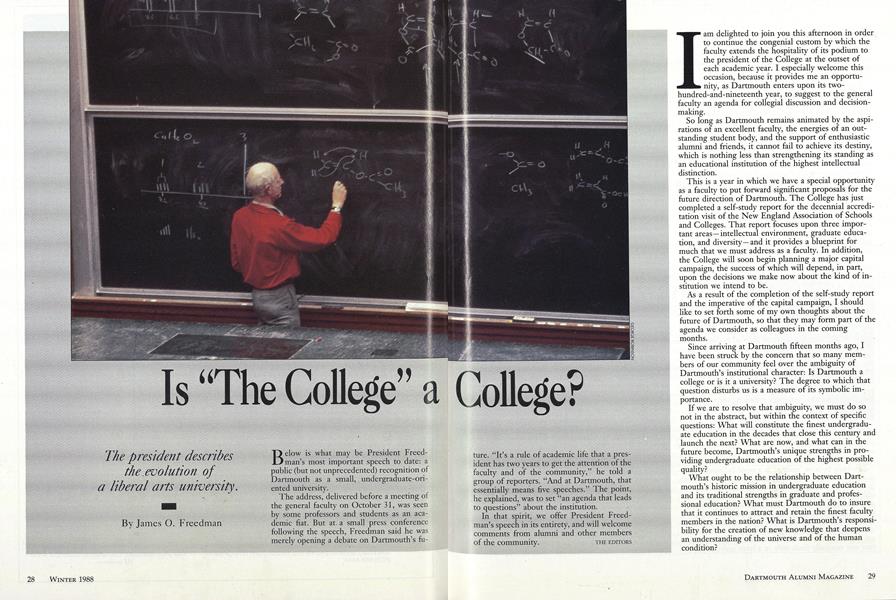

The president describes the evolution of a liberal arts university.

Below is what may be President Freedman's most important speech to date: a public (but not unprecedented) recognition of Dartmouth as a small, undergraduate-oriented university.

The address, delivered before a meeting of the general faculty on October 31, was seen by some professors and students as an academic fiat. But at. a small press conference following the speech, Freedman said he was merely opening a debate on Dartmouth's future "It's a rule of academic life that a president has two years to get the attention of the faculty and of the community," he told a group of reporters. "And at Dartmouth, that essentially means five speeches." The point, he explained, was to set "an agenda that leads to questions" about the institution.

In that spirit, we offer President Freedman's speech in its entirety, and will welcome comments from alumni and other members of the community.

THE EDITORS

I am delighted to join you this afternoon in order to continue the congenial custom by which the faculty extends the hospitality of its podium to the president of the College at the outset of each academic year. I especially welcome this occasion, because it provides me an opportunity, as Dartmouth enters upon its two-hundred-and-nineteenth year, to suggest to the general faculty an agenda for collegial discussion and decisionmaking.

So long as Dartmouth remains animated by the aspirations of an excellent faculty, the energies of an outstanding student body, and the support of enthusiastic alumni and friends, it cannot fail to achieve its destiny, which is nothing less than strengthening its standing as an educational institution of the highest intellectual distinction.

This is a year in which we have a special opportunity as a faculty to put forward significant proposals for the future direction of Dartmouth. The College has just completed a self-study report for the decennial accreditation visit of the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. That report focuses upon three important areas—intellectual environment, graduate education, and diversity—and it provides a blueprint for much that we must address as a faculty. In addition, the College will soon begin planning a major capital campaign, the success of which will depend, in part, upon the decisions we make now about the kind of institution we intend to be.

As a result of the completion of the self-study report and the imperative of the capital campaign, I should like to set forth some of my own thoughts about the future of Dartmouth, so that they may form part of the agenda we consider as colleagues in the coming months.

Since arriving at Dartmouth fifteen months ago, I have been struck by the concern that so many members of our community feel over the ambiguity of Dartmouth's institutional character: Is Dartmouth a college or is it a university? The degree to which that question disturbs us is a measure of its symbolic importance.

If we are to resolve that ambiguity, we must do so not in the abstract, but within the context of specific questions: What will constitute the finest undergraduate education in the decades that close this century and launch the next? What are now, and what can in the future become, Dartmouth's unique strengths in providing undergraduate education of the highest possible quality?

What ought to be the relationship between Dartmouth's historic mission in undergraduate education and its traditional strengths in graduate and professional education? What must Dartmouth do to insure that it continues to attract and retain the finest faculty members in the nation? What is Dartmouth's responsibility for the creation of new knowledge that deepens an understanding of the universe and of the human condition?

An outside observer who came to Hanover to examine Dartmouth would quickly conclude that it is no longer the small liberal arts college that it was a century ago. It has long since become a liberal arts university. Indeed, the evidence is all around us and impressively so.

First, Dartmouth offers its students a curriculum in the arts and sciences of a breadth and quality characteristic of a university. Second, Dartmouth maintains three outstanding professional schools: the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration, the Thayer School of Engineering, and the Dartmouth Medical School. Each has a venerable tradition. Each, in President John Sloan Dickey's words, "maintains an extraordinarily close, mutually rewarding relationship to the total life and work of Dartmouth." Third, Dartmouth offers 11 doctoral programs in the natural and social sciences, a master of arts in liberal studies, and a newly established master's program in the humanities. Fourth, Dartmouth has steadily built an outstanding research library, now numbering 1,750,000 volumes one that has earned an enviable reputation as a national center for scholarship. Fifth, Dartmouth has appointed a faculty of devoted scholars, nationally and internationally prominent, who are dedicated to research and to exploration of the frontiers of knowledge.

Although external support is only one measure of scholarship, the level of sponsored research at Dartmouth has doubled in the last five years, to some $38 million in 1987-88, an extraordinary performance in an era of restricted support by government and foundations. During the last academic year alone, research awards to the faculty of the Medical School have increased by 25 percent and those to the faculty of arts and sciences by 20 percent.

These facts describe an outcome that is the product of many decades of evolution, beginning with the founding of an undergraduate program emphasizing the quality of teaching; moving to the maturation of our professional programs in business administration, engineering, and medicine combining professional preparation with faculty research; and advancing to the creation of doctoral programs reflecting the faculty's growing commitment to advanced study and the rewards of scholarship.

Twenty-four years ago, in 1964, President Dickey remarked upon the number of newcomers to a knowledge of Dartmouth who asked him, in some amazement, "But then you are a university?" And 13 years ago, in 1975, President John G. Kemeny wrote:

"Perhaps because 'college' is a word hallowed by tradition, we sometimes overlook the fact that Dartmouth is a small university. Yet Dartmouth has the fourth oldest medical school in the country, one of the first professional schools of civil (as opposed to military) engineering, and the oldest graduate school of business administration. In more recent years we have added small, selective Ph.D. programs. Coupled with these are facilities such as a million-volume research library' that one normally finds only in a large university. Being a full university which has placed its overwhelming emphasis on undergraduate education is a major part of the uniqueness of Dartmouth College."

Lest there remain any doubt of the result of this long course of evolution, it is important for us to assert confidently and unambiguously that Dartmouth is a liberal arts university. We are a liberal arts university committed to the primacy of liberal learning at the undergraduate, graduate, and professional levels. We are a liberal arts university committed to a set of aspira tions rooted in our history and unique to our strengths. We are a liberal arts university that does not seek to become a traditional, large scale, highly impersonal research university. Rather, we are a liberal arts university that seeks to become the very best of what we already are.

Dartmouth intends to be a special kind of academic institution—one that emphasizes the undergraduate experience in the liberal arts and sciences; one that insists upon the companionate roles of teaching and research as mutually nourishing elements of an undergraduate education unsurpassed in excellence by any college in the country; one that cherishes the intellectual stimulation generated in the classroom by faculty members, graduate students, and undergraduates involved in scholarship and research at the forefronts of their fields; one that recognizes the opportunities for rich intellectual exchange among the several schools and the many disciplines on our campus; one that calls upon the imagination of the entire institution to create an intellectual universe that fully nurtures the life of the mind.

By defining Dartmouth as a liberal arts university, we will more confidently proclaim that we are a community of scholars with the same close intellectual ties between faculty and students and the same vigorous enthusiasm in the robust exchange of ideas that have always been Dartmouth's strengths.

We will insure that faculty members communicate to our students, who are among the most talented and gifted in the nation, the excitement of intellectual discovery and intellectual risk-taking, by igniting in them what Horace Judson calls "the rage to know." We will provide our students with research and writing opportunities that will enable them to produce new knowledge and creative work of their own.

We will seize to foil advantage the unusual opportunity that Dartmouth has, by virtue of its compact campus, to promote an extensive measure of collaboration among faculty members and undergraduates, as well as among our undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs.

By acknowledging-that the research strengths and aspirations of the faculty are an integral part of undergraduate education, we will underscore the indispensable role that scholarship plays in nourishing and deepening the quality of undergraduate teaching. We will affirm the importance of scholarship and research for the entire length of a professor's academic career.

And whether our students ultimately choose careers in business, science, law, education, the arts, or public service, the strength of mind and character inherent in rigorous and imaginative scholarship will be an enduring personal legacy of their education at Dartmouth.

Why does it matter that Dartmouth emphatically state that it has become, through the cumulative decisions of decades, a liberal arts university? It matters for at least five reasons:

First, we must dispel whatever ambiguity may still remain about the true character of Dartmouth's academic enterprise. As we affirm that scholarship and research infuse teaching with a special excitement and vigor, especially at the undergraduate level, we will be even more successful in meeting our most fundamental educational aspirations.

Second, Dartmouth's faculty and curriculum must keep pace, in the decades ahead, with emerging ideas of new knowledge areas that have in common a challenging agenda of tantalizing mysteries, areas that invite exploration by wise, resourceful, and creative minds, often using new emerging technologies. During the last several years, the faculty has spoken its commitment to these frontier areas by proposing, creating, or strengthening such programs as linguistics and cog nitive science, visual studies, drama and film studies, electro-acoustic music, Latin American and Caribbean studies, Asian studies, applied and professional ethics, molecular genetics, neuroscience, laser science, and biomedical engineering. By emphasizing academic areas of such a research-oriented character, the faculty has committed itself to what Francis Bacon called "the advancement of learning" and has recognized the centrality of scholarship to both what and how well we teach our students.

Third, by acknowledging that Dartmouth is a liberal arts university, we will strengthen our ability in the years ahead to attract the strongest possible faculty members and to prevent the loss to large research universities of talented members of our present faculty.

Ernest Martin Hopkins said at the College's onehundred-and-fiftieth anniversary celebration, in 1919, "I hold it true beyond the possibility of cavil that the criterion of the strength of a college is essentially the strength of its faculty. If the faculty is strong, the college is strong; if the faculty is weak, the college is weak."

As we continue to measure the strength of the College by the strength of its faculty, we must be able to assure the most talented young scholars embarking upon academic careers that Dartmouth, even more than competing institutions, values both teaching and scholarship as essential responsibilities and opportunities.

Fourth, in the intense competition for the nation's most gifted students, colleges and universities will be judged by the academic rigor and the intellectual excitement of the undergraduate experience that they offer. The surest guarantee that Dartmouth will always provide that rigor and excitement is to expect our faculty to remain at the forefront of scholarship and research, so that they may share with their students the trials and tribulations, the wonder and joy, of discovering new truths and conveying new ways of seeing and understanding.

Fifth, we will provide a rationale for enhancing intellectual interaction among the faculty of arts and sciences and the faculties of the professional schools, so that the intellectual achievements and satisfactions of both faculty members and students may be truly synergistic, as well as significantly greater than the sum of the individual parts.

Proclaiming that Dartmouth is in fact a liberal arts university will almost certainly have several consequences. We will attract a greater level of support for sponsored research, thereby decreasing our excessively high reliance on endowment income, tuition, and annual giving. We will need to reduce the demands that serving on faculty committees makes upon our time, if we are to give our scholarly pursuits a larger role in the way we teach undergraduates. (As essential as collegial governance is to a mature educational institution, something is askew when faculty members report, as they did in the recent self-study, that committee work consumes a disproportionate amount of their time when compared to teaching, research, and meeting with students.)

Finally, we will want to plan for an increase in the size of the faculty, so that faculty members will have adequate time to meet the heightened expectations, in both scholarship and teaching, ,to which we will be committing ourselves. And we will need to increase the size of the faculty for two further reasons: to provide colleagues for individual faculty members who currendy have, virtually by themselves, the responsibility of covering large substantive areas and, also, to enrich the breadth and extend the reach of the curriculum that we offer.

As Dartmouth emphasizes its status as a liberal arts university, it must be guided, as it has been for so long, by a profound faculty commitment to undergraduate teaching, to discovering new knowledge in collaboration with students, and to achieving distinction in scholarship and research. It must encourage faculty participation in interdisciplinary teaching and research. And it must seek the development of a unique role for graduate education, instilling the values of a liberal arts approach to the study of advanced and highly specialized subjects.

What would be the implications for our curriculum in explicitly recognizing our role as a special kind of liberal arts university? Although we organize ourselves as a faculty along traditional departmental and disciplinary lines, we increasingly define ourselves as intellectuals and scholars along programmatic and interdisciplinary lines. Few would suggest that we abandon the departmental structure, if only because of the basic strength that the disciplines, as conventionally defined, impart to a curriculum.

But this faculty is itself increasingly recognizing that the taxonomy of knowledge is, all too often, not reflected by traditional disciplinary paradigms. It is increasingly proposing interdisciplinary courses and programs organized around more congenial intellectual alliances, in order to keep pace with new connections between established and emerging areas of knowledge.

Not every generation has adapted successfully to new configurations of knowledge. We marvel in dismay today that the Clapham Committee, writing in Great Britain just after World War II, could advise against establishing the Social Science Research Council, because it regarded the disciplines involved as prone to "a premature crystallization of spurious orthodoxies."

Recent faculty initiatives at Dartmouth suggest the importance of devising means to encourage faculty members to think of education in ways that stress authentic intellectual connections and the creation of a curriculum that would enable faculty members to be intellectually engaged with one another, across disciplinary lines. Let me suggest three areas in which such faculty initiatives are already underway, although there are many others that could well be considered, too.

The first is the teaching of creative writing to undergraduates, thereby encouraging the aspirations of those students who want to test and nurture their talents as novelists, short-story writers, poets, and playwrights. The second is the widening of our programs in international education and foreign-language instruction, thereby responding to the increasing interdependence of the many nations and cultures of the world, both Western and non-Western, and better preparing our students for what many of us believe will be the "Century of the Pacific." The third is the joinder of our common strengths in environmental studies, policy studies, and ecology, thereby taking advantage of our privileged geographical location and our longstanding commitment to preserving the quality of the planet's natural environment. Whether we move forward in these areas or many others of equivalent importance will depend, ultimately, upon faculty initiative and support.

Nothing is more essential to the special kind of liberal arts university that we seek to maintain at Dartmouth than the emphasis we place on the quality of the undergraduate experience. Given the superb caliber of our undergraduates, we must be certain that we are encouraging them to stretch themselves to the fullest and expect as much of themselves as their high talents warrant. We need constantly to review the intellectual rigor of our curriculum, so that when students graduate from Dartmouth, they have learned to think critically, \to reason carefully, to express themselves effectively, to reflect thoughtfully, to respond humanely, and to care about what I have heretofore styled the development of both their public and their private selves.

In emphasizing the primacy of undergraduate education in a liberal arts university, we ought to regard the senior year as the intellectual capstone of our students' academic encounter—the time when they experience the supreme joy of original achievement. We must encourage more of our students to commit themselves to full intellectual engagement, especially by writing honors theses and otherwise engaging in independent study.

At the present time, only ten percent of our students write an honors thesis, even though approximately 30 percent are eligible to do so. We should examine the rules of eligibility for honors theses and independent study with a sympathetic eye to assure that as many students as possible graduate from Dartmouth having discovered as fully as possible the satisfactions that come from truly independent learning, intellectual mastery, and exacting craftsmanship.

As we create new intellectual challenges for our students, we must also be certain that we make them aware of the richness of career opportunities that are open to those who have engaged in the venture of liberal learning. I express again, as I did a year ago, the hope that a higher percentage of our students will seek Ph.D.'s and careers in the academic world, the sciences, and the visual and performing arts so that Dartmouth graduates will be significant leaders in these areas, as they have been in so many others, and that they will play important roles in helping their generations to understand better the mysteries of the universe and the haunting dilemmas of the human condition.

Finally, as a liberal arts university, Dartmouth must attend to the future of its professional and graduate programs, which now enroll approximately 1,000 students. Although Dartmouth awarded its first Ph.D. (in the classics) in 1885, the first doctoral programs in modern times were not established until 1960. These programs have gradually become a vital part of the entire institution, and the most important issues we now face relate to the criteria by which we should establish and measure the quality of our professional and graduate programs.

Dartmouth's three professional schools have been distinguished, during their long histories, by the integration of a liberal arts philosophy into their curricula. They have achieved national distinction for doing so. As pressures mount within the professions themselves for increasing specialization, we must be vigilant in maintaining the philosophic breadth and intellectual vigor of these programs.

When doctoral programs have been established at Dartmouth, often they have been justified as necessary to attract and to retain a strong faculty for the teaching of undergraduates. The argument has been that Dartmouth needs graduate programs in order to enable faculty members, primarily in the sciences, to engage in research that will, in turn, induce them to remain at Dartmouth.

But we have never been entirely clear about whether we expect our graduate programs to be among the very strongest in the nation or merely sufficiently strong to satisfy the professional needs of faculty members who might leave Dartmouth if we had no such programs at all.

We have typically declared, in establishing new graduate programs, that existing financial resources shall not be diverted from other purposes in order to support them. And we have not formally stated for our graduate programs the expectations of preeminent excellence and of national recognition that we have long taken for granted for our undergraduate programs.

Perhaps for these reasons, our graduate programs have had uneven success in attracting external support for sponsored research and are sometimes regarded, within the Dartmouth community, as subsidiary and peripheral to the larger educational enterprise, thereby causing many of our doctoral students to feel marginal and undervalued.

We need to undertake a renewed inquiry into the goals of graduate education at Dartmouth and to achieve a better articulation of the mutually reinforcing relationship we intend between undergraduate and graduate education. In what ways do we expect graduate programs to complement undergraduate programs? What is the relationship between the maintenance of graduate programs and the research achievements of the faculty? What ought to be the size of our graduate programs in order for them to provide the critical mass of students necessary for a meaningful academic experience?

What strategies are necessary to insure that Dartmouth attracts superior graduate students, destined to be among the leaders of the next academic generation? To what extent are our doctoral students in as great demand for faculty appointments at first-quality institutions across the country as the doctoral students of those institutions are in demand at Dartmouth? To what degree can a liberal arts university, one that does not seek to become a University of traditional character, create a vibrant intellectual environment without necessarily establishing a full panoply of doctoral programs?

Once we have carefully considered these questions and others like them, we will be in a better position to determine the future shape of graduate education at Dartmouth. We will also be in a better position to assess whether support for faculty scholarship and research, especially in the social sciences and the humanities, may sometimes be best provided not by the creation of new graduate programs but by the establishment of such institutions as the School of Criticism and Theory and the Humanities Institutes, as well as by the encouragement of full faculty participation in research institutes, seminars, and colloquia.

Acknowledging that Dartmouth is indeed a liberal arts university, we now confront the historic opportunity of building upon the achievements of the past to define an intellectual and academic world that is unique to Dartmouth.

In so doing, we must further emphasize the vital importance of scholarship and research in enriching undergraduate teaching. And we must further explore how we can engage undergraduates in the collaborative process of discovering knowledge, how we can encourage imaginative new interdisciplinary approaches to learning, how we can enlarge the opportunities we offer seniors for the challenge of honors theses and independent work, and how we can determine the ongoing role that professional and graduate education should play in strengthening the entire institution.

Even as we proudly adhere to the rich heritage summoned up by Dartmouth's designation as a "College," even as we gratefully preserve our loyalty to the values that Daniel Webster and successive generations have loved so dearly, we shall succeed in farther achieving Dartmouth's destiny as a commonwealth of liberal learning that enriches the lives of its students and contributes effectively to the life of the nation and the world.

"Nothing is more essential to the special kind of liberal artsuniversity that we seek to maintain at Dartmouth than theemphasis we place on the quality of the undergraduate experience."

"We are a liberal arts university committed to a set ofaspirations rooted in our history and unique to our strengths."

A College Evolves 1769: Dartmouth founded. 1797: Medical School established. 1816: Dartmouth University founded. 1819: Supreme Court decides in favor of College over University. 1850: For $5.00, each bachelor-degree holder out of Dartmouth for more than three years can obtain a master of arts degree. 1871: Thayer School founded. 1885: Dartmouth awards its first Ph.D., in the classics. 1899: Tuck School founded. 1930: The three original Ph.D. programs come to an end. 1960: Doctoral programs introduced in molecular biology and physiology. 1967: The College now has eight Ph.D. programs in math, engineering and the sciences. 1970:Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Program established. 1987: Dartmouth ranked sixth among national research universities by U.S. News & World Report. 1988: Doctoral program in electro-acoustic music approved by Trustees. President Freedman declares Dartmouth a liberal arts university.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Compleat Engineer

December 1988 By Samuel C. Florman '46 -

Feature

FeatureIs Vietnam Still Claiming Some of Us?

December 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Who Invented the Ant Farm (Not to Mention the Ant Coal Mine)

December 1988 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleCUTTING BONE

December 1988 -

Article

ArticleBEYOND INTUITION

December 1988 By J. Laurie Snell -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

December 1988 By Eric Grubman

James O. Freedman

-

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleTHE PROFESSOR'S LIFE

FEBRUARY 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA ROBUST INTELLECTUAL

APRIL 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE CONCEPT OF HEROISM

MAY 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Word to The Able

December 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe New Great Issues

OCTOBER 1994 By James O. Freedman

Features

-

Feature

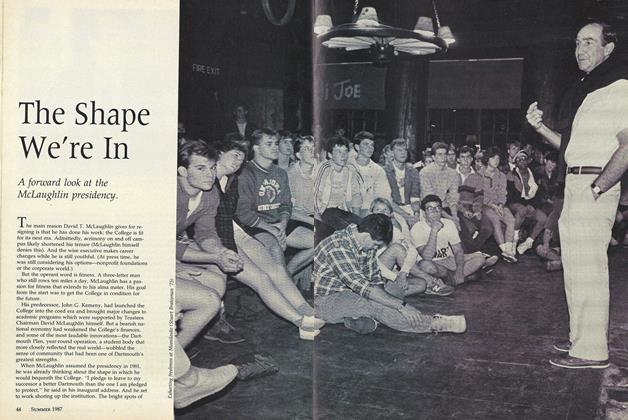

FeatureThe Shape We're In

June 1987 -

Features

FeaturesMixed

MAY | JUNE 2014 -

Feature

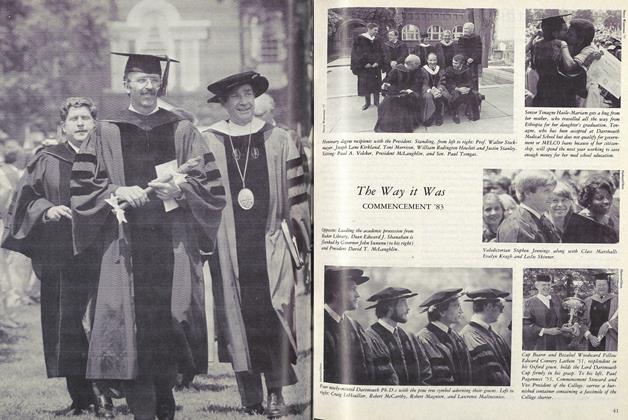

FeatureThe Way it Was

JUNE 1983 By COMMENCEMENT '83 -

Feature

FeatureFrom Dartmouth Comes the World's First Love Story

MARCH 1989 By David Birney '61 -

Feature

FeatureIdea Entrepreneurs

April 2000 By JANE HODGES '92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

JUNE 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83