LECTURE

Will aliens from outer space ever pay Earth a visit? Unfortunately for science, the assumptions we humans tend to make about such creatures may prevent us ever from recognizing visitors when they arrive (as, indeed, they may already have done).

In 19791 was a member of a NASA study group charged with designing a system to detect alien signals that might be embedded in radio waves emanating from outer space. As one of the few social scientists in a group dominated by engineers, physicists and astronomers, I was dismayed at how quickly the group settled on a narrow conception of what form a message from outer space might take. We consider sending messenger probes; therefore "they" will send probes. We rely heavily on radio communication; therefore "they" will rely heavily on radio. We consider making contact by repeating radio and TV transmissions; therefore "they" might signal their presence in the same way.

Almost a decade later, NASA continues to reveal the same provincialism. The space agency has asked Congress for $100 million to be spent on a search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) over a ten-year period. This is the ultimate crosscultural communication challenge; yet the agency is not planning to involve linguists, anthropologists, psychologists, sociologists, or other social scientists in any significant way.

NASA's scientific chauvinism nicely illustrates a common psychological phenomenon. People project human qualities into space and, in particular, attribute human motivation to aliens. Thus when SETI scientists discuss the content of potential messages, the conversation eventually gets around to the assumption that introductory courses on the cosmos, held by alien instructors, will address issues in physics, chemistry, and mathematics. This hopeful scenario arises quite naturally because those are the topics most valued by the scientists who want to launch probes from this planet to perform similar dudes in outer space.

Of course, the reality may be utterly different. Who is to say, for instance, that the nearest alien civilization is not composed entirely of humanities majors? In fact given the potential variety of life-forms in outer space we should not be too surprised if extraterrestrials are vastly different from humans, either in the nature of their intelligence or in the social values held most dear.

Even on Earth we have had only minor success in communicating with our closest intellectual relatives, chimpanzees and dolphins. According to the astrophysicist John A. Ball, contact with extraterrestrials would be something like a conversation between a person and a clam where the stupider one is us. It is doubtful that clams have a very accurate picture of human nature, and the same inadequacy would be expected of our evaluation of an intellectually advanced being from quite another sphere of existence.

Suppose we do discover an alien culture with intellects comparable to our own. Many barriers to communication would remain; one of them is time. Our chronological perception follows naturally from the geophysics and biology of this planet. All animals are influenced by the cyclical changes of the massive bodies of the Solar System, and the influence is evident in major patterns of rhythmic behavior. The length of a thought, a linguistic expression, the patterning of words, and indeed the entire structure of language may depend on temporal rhythms defined by geophysical events peculiar to Earth and the solar system.

Governments engaged in pure research rarely fund projects beyond five years at a clip, and often the scope is more like two, but suppose an alien civilization exists whose members live ten times longer than we? Might their time scale for sending messages be greatly expanded? They could see a human hour as totally inadequate for saying anything the least bit interesting, and thus the time we would require to detect a pattern in their radio signals would increase proportionally. Instead of a few hours of observation per star, we would be forced to look for hundreds of hours, and instead of five-year grants, we would need a few centuries of guaranteed financial support.

Before we can understand the thoughts of intergalactic neighbors, we must begin to understand ourselves better a noble goal even if we never establish contact with intelligent aliens. With the help of knowledgeable social scientists, SETI's cosmic exercise in communication would force us to look at our own civilization on Earth from the point of view of an alien. At no time in history has such planetary introspection been more crucial. Perhaps by seeing ourselves from such a distance, we would better appreciate the limits and potential of human intelligence and maybe even gain the wisdom needed to solve such earthly problems as the threat of nuclear annihilation, the depletion of our natural resources, and the population explosion. As the poet Robert Burns wrote: Oh wad some power the giftie gie us To see oursels as others see us! It wad frae monie a blunder free us, An' foolish notion. mm

Jack Baird is professor of Psychology and Mathematics/Social Science at Dartmouth. This essay was adapted with permission from his latest book, The Inner Limits of Outer Space, published for the College by the University Press of New England.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWelcoming the Loner

September 1988 By Victor F. Zonana '75 -

Feature

FeatureFrom America's Lost Cohort, the Shards of Souls

September 1988 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

September 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

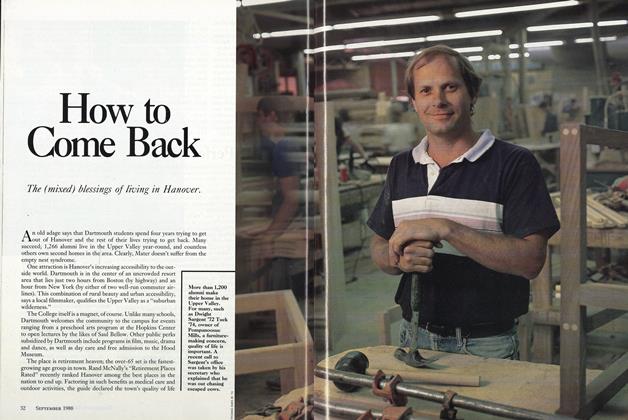

FeatureHow to Come Back

September 1988 -

Sports

SportsFall Sports Preview

September 1988 -

Article

ArticleRush Delayed

September 1988 By Jack Steinberg '88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDaughters of Dartmouth

NOVEMBER 1988 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

MARCH 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

FeatureA Shapely Punctuation Mark

July 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureIt’s the Ideas, Stupid

April 2000 By KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81 -

Feature

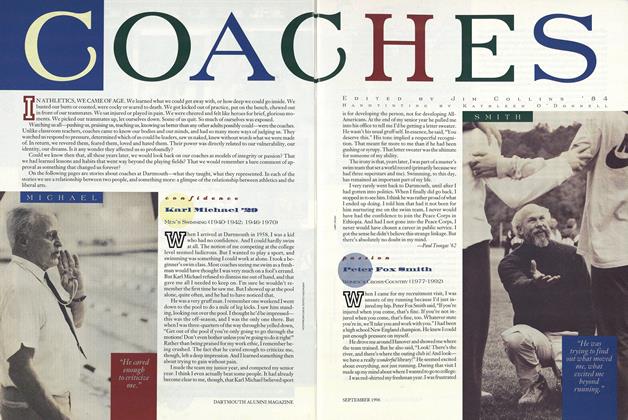

FeatureConfidence

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Paid Tsongas '62