Edward Mortimer, Faith and Power: The Politics of Islam (Vintage Books). A well-written and well-informed journalistic account of modern Islam by—no surprise a journalist.

Ruhallah Khomeini, Islam and Revolution: Writings and Declarations of Imam Khomeini translated and annotated by Hamid Algar (Mizanpress). Not a thrilling read, but Westerners who think the Ayatollah is a fool ought to read this work—if not to agree with him, at least to grasp his intelligence and passion. Alas, Algar's is the only reliable translation; others, including the one done for the intelligence community, are embarrassingly bad, which may help explain the success of American policy in the Middle East.

T.E. Lawrence, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (many editions). Read carefully, this twentieth-century classic is both the quintessence of orientalist stereotypes about "The East" and their refutation.

Jonathan Raban, Arabia: A Journey Through the Labyrinth (Simon and Schuster). Raban's book is one of the few humane travel accounts on the Middle East. He assumes his subject's humanity, and he reflects upon himself as a foreigner in ways that will please anyone who has traveled in the Third World. His starting premise is this: Here I am in London, and all of a sudden I see all these Arabs. Who are they, and where do they come from? A very subtle book.

The Message of the Qur'an translated and explained by Muhammad Asad. (Dar al-Andalus). A contemporary translation and interpretation by an Austrian convert who has lived with the Bedouin and who was Pakistan's ambassador to the United Nations. This translation is intelligent and stimulating, and although Asad sometimes exceeds the actual text, readers of his translation are in touch with a creative Muslim understanding of how the text can be used.

M.G.S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization (University of Chicago Press). It might seem that a threevolume history of Islam and Islamdom is an example of wretched academic excess, but this work confounds expectations: it is, for instance, the only book on Islam that I've ever seen reviewed (and praised) in The New Yorker. Readers who spend time with this book will understand Islamic civilization better than a lot of "professionals" and will also have their view of history changed (for the better). A challenging, exciting, subversive work by a brilliant University of Chicago professor. Islamic history for people who aren't sure why they should care.

Michael Gilsenan, Recognizing Islam (Pantheon Books). An anthropologist looks at the Islamic world, and though he is weak (as anthropologists often are) on history, he is strong (as Islamicists often are not) on interpreting the whole of contemporary culture.

Fouad Ajami, The Vanished Imam: Musa al-Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon (Cornell University Press). A brilliant book about Musa Sadr, the religious leader who mobilized the Lebanese Shiite community into a political force and led them brilliantly until he was kidnapped, and probably killed, by Libya's Khaddafi. One of the few books that explain how Islam is attractive for the oppressed and abused, it also demonstrates that Islam's universalist ideals allow a "foreigner" to figure in the renewal of a national community.

Roy Mottahedeh, The Mantle of the Prophet (Pantheon). An elegant book that might be called "My Life as a Mullah." The author (an American of Iranian-Bahai background) interviewed several Iranian scholars at great length and added his own reflections on Islam. The result is a biography that is also an attractive introduction to the Islamic intellectual cosmos. Students love it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWelcoming the Loner

September 1988 By Victor F. Zonana '75 -

Feature

FeatureFrom America's Lost Cohort, the Shards of Souls

September 1988 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Feature

FeatureIn the Galactic Search for Intelligence, We May Find Ourselves

September 1988 By Jack Baird -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

September 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureHow to Come Back

September 1988 -

Sports

SportsFall Sports Preview

September 1988

Article

-

Article

ArticleCouncil Nominees from District III

May 1947 -

Article

ArticleBets on the Future

January 1955 -

Article

ArticleTwenty Years Old

December 1961 -

Article

ArticleGraduate Awards

JULY 1972 -

Article

ArticleCount Rumford and DOC Fireplaces

MAY 1963 By ALLEN P. RICHMOND JR. '14 -

Article

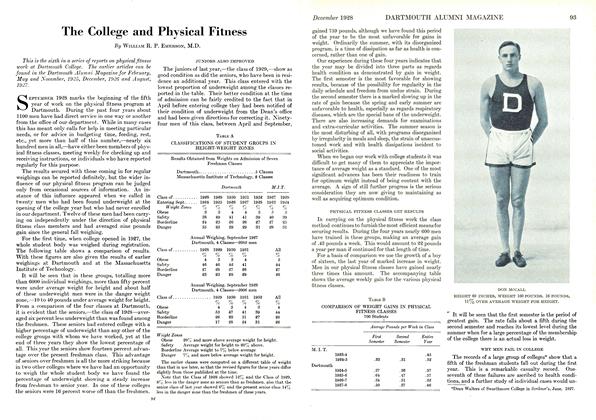

ArticleThe College and Physical Fitness

December, 1928 By William R.P.Emerson, M.D.