Traversing culture and place, travel

Forget the tradition that journeys are metaphors for life; to the serious traveler, life is a metaphor for journeying. Starting out is a birth, coming home a death. The most serious travelers refuse to come home at all. For them, the excitement and joy of travel come from being in between.

Most of us are too impatient, too practical, or too lazy for such perfection. Some take the attitude of Voltaire toward Boswell and Johnson's Hebridean jaunt: '"You do not insist on my accompanying you?''No, sir. 'Then I am very willing you should go.'" Others are what Nigerians call "been-tos": we've seen it, we've smelled it, and by damn we know it. Whether as vicarious adventurers or as opinionated been-tos, we don't have the temperament of travel writers. Our minds do not linger in the middle of the journey, in the dark wood.

Some travel books began as journals, written as the rain smashed down or the scent of warm gum-leaves hung in the air; others are recollections in some version of tranquility. Always, however, the author must feel that he is in between, between not only arrivals and departures but one way of life and another.

Remembered away from their books, some travelers still figure in a landscape. I think, for example, of three Victorian Britons: Mary Kingsley climbing West African mountains in long woolen skirt, sensible blouse, and bright red silk necktie; Charles Waterton astride a giant alligator by a muddy Guyanan creek; George Borrow setting off into the Welsh mists with a tolerable knowledge of twelfth-century verse and a very necessary umbrella. Some people would call such individuals "intrepid"; entirely without malice or opprobrium, I favor "independent" and "absurd." Whoever the surrounding people Tuaregs, Venetians, Aranda, Alabamans the best writers know themselves as stranger creatures than their subjects.

Travelers are tolerators or denouncers, putters-up or putters-down; among the writers listed below, for instance, Mary Wortley Montagu belongs to the first group, Flora Tristan to the second. Both kinds of writer, however, start from a relish of human variety. A hatred of difference by skin, by gender, by class, by language, by belief has led our species into sleazy alleyways. But laying out the sunny boulevards of uniformity does its own kind of damage: Gleichschaltung the Nazis called it, switching onto the social main line.

Travel writers, then, coexist with difference in a healthy tension between seeing and being seen. Of course we read them to learn about a place elsewhere or, when we take up, say, Jonathan Raban's The Old Glory, the story of a voyage down the Mississippi, to learn about our place right here. Travel books are mirrors, lenses, prisms, what you will, of something that isn't entirely the product of the traveler's imagination or the superstitions of the traveler's own tribe. But the mirrors are convex or concave, the lenses tinted, the prisms made to refract in curious ways, and therein lies the pleasure and the profit.

When I write a syllabus, what I mostly profess is regret. So many marvels, so little time. As books about travel, rather than as travel books, the first three readings below frame the rest of the list. I've had to exclude at least two dozen more authors. Those who do appear take their places on the raft not only because they're good in isolation, but because they keep good company together.

When not off the beaten track, Laurence Davies edits and annotates author Joseph Conrad's papers.

He reads everything. That's the word on campus about Laurence Davies, senior lecturer of English. Amid stacks of books in his living room in the faculty master's quarters at the Choates dormitory complex, however, Davies waves off the reputation, instead characterizing himself as "someone who can't resist books." Also someone who can't resist traveling—his wanderlust got underway when he hitchhiked at age 14 from England to Franco's SpainDavies revels in travel books, the literary genre that brings the world to one's armchair.

"I like quirky individualists, travel writers like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Norman Lewis who are

humanely skeptical, not cynical, but not taken in either—-writers with a burning curiosity to know," says Davies. Not all travel writers earn his praise. "'I here are some very smug and stupid travel books rich only in the obvious prejudices. Yet I agree with the writer Paul 1 heroux that good travel writers often understand politics better than the pundits."

From the start Davies was an observer of people and places. Born in Wales, he grew up in London. He says, "This led me to see things from the outside and to think about how people come to terms with being outsiders. I thought a lot about racial prejudice when my Welsh friends denigrated the Lnglish. Their words did not match what I knew to be true. The Welsh and English have been at peace for 500 years but they are at each others' throats verbally. I became fascinated with how people misconstrue each other."

Davies traveled the world before settling into doctoral studies at the University of Sussex. He wrote a dissertation and book on the Scottish writer Cunninghame Graham, who lived in Latin America and wrote histories of the Spanish Conquest and—what else?—travel books. Indirectly, it was Graham who lured Davies to Dartmouth: Graham's correspondence with the writer Joseph Conrad had been acquired for Dartmouth by English Professor Herb West. Davies's research led him to these archives at Baker Library. Since 1978 he has been coediting and annotating Conrad's voluminous writings. "When Conrad left his native Poland he became a sailor a wanderer," he says. "Even after 11 years on the project I find I like him more and more." Davies's post-Conrad plans: "an orgy of travel."

Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBEYOND ME

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

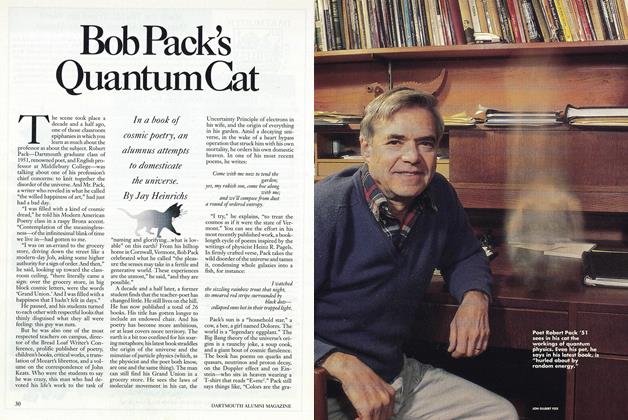

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

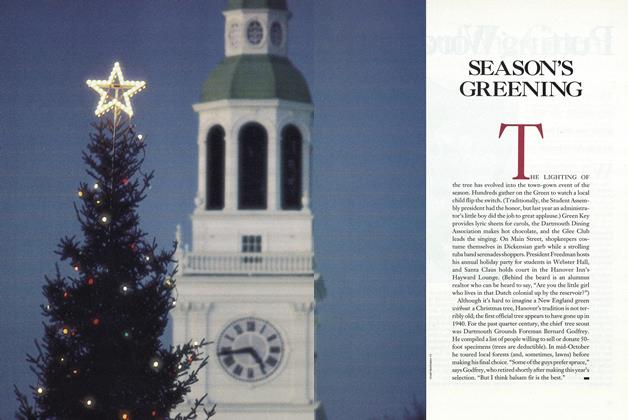

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1989 -

Sports

SportsThe College's First Fan Picks a Winner

December 1989 By Noel Perrin

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

January 1916 -

Article

ArticleENGLISH SPEAKING UNION RECEIVES LIBRARY FUNDS

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

ArticleMovies Released

February 1934 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

April 1937 -

Article

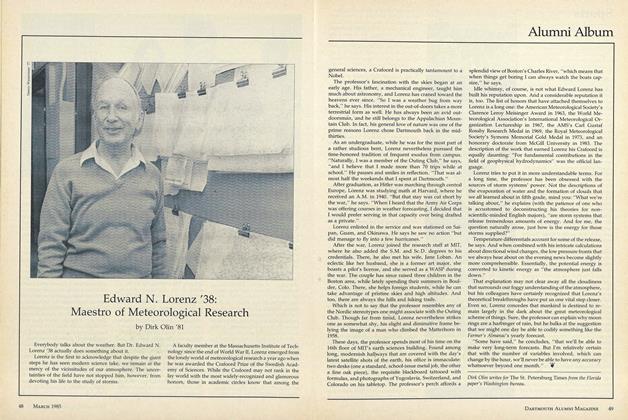

ArticleEdward N. Lorenz '38: Maestro of Meteorological Research

MARCH • 1985 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

March 1948 By H. L. Duncombe JR.