Science fiction conducts experiments on the human condition.

No one would dream of teaching a college course composed of Harlequin romances. The reason is simple. Harlequins are not literature, but products daydreams-for-rent, written according to a small number of rigid formulas, mass-produced, loaded with cliche.

Some people have thought science fiction ("sf ") was also a formulaic genre, unworthy to be taught. Some people still do. Are they ever wrong!

The error is understandable, though, because sf is easily confused with two related genres that are formulaictwo seedy cousins, so to speak. If you were to pose the three for a group picture, you would put sfin the middle, clean-faced and intelligent. On one side, wearing stage armor, would be the sword-and-sorcery novel. On the other, holding a couple of laser pistols and wearing a gaudy helmet, space opera. (And if you wantfed a really complicated family photo; you would also put the sword-and-sorcery novel's father in back. That genre, a very old one, is called heroic fantasy. It includes Beowulf, the Morte D:' Arthur, and Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, the work that is gloriously and direcdy responsible for the recent mass of sword-and-sorceries.)

Sf differs from its cousins not only in quality but in kind. It's not that good sf gets called that, while the bad is dismissed as space opera. There is a clear distinction. In both space opera and sword-and-sorcery, the human will is unlimited. You can do anything. In space opera, the "anything" will be dressed up in scientific-sounding terminology, so that if you want to travel faster than light you invent something called a "space warp." But you would not be able to offer even a ghost of a theory as to how a space warp would work.

In sf, however, no fact is ducked. Even to distort one would spoil what you are doing. Because the great aim of sf is to ask what-if questions, and then to answer them at once imaginatively and truthfully. What if human beings were to develop a form of secular immortality, right here on this planet? (This is no wild-eyed question, either. People like Marvin Minsky, the Donner Professor of Science at MIT, firmly believe that we will be able to transfer ourselves into long-lasting if not actually immortal computer forms in the not very distant future.) What if human population reaches 14 billion—as, by current growth rates, it will about the year 2100? How will that affect what we regard as normal life?—Noel Perrin Many science fiction novels arefine pieces of literature—fine, like other masterworks, because they raise the most important, ineffable questions about man's nature and spirit, his relationship to his god and to eternity as well as to other creatures of all kinds in the here and now.

Sf like Walter M. Miller Jr.'s ACanticle for Leiboivitz serves the same literary purpose as, say, Robinson Crusoe (1719), and in many of the same ways. They rip human beings out of familiar environments—in which their humanness is masked by comfortable layers of a particular culture—and expose them to culture-free and timeless tests of survival, meaning, and transcendence. It is the simplest way of telling what's truly human and what's not. As an exercise in this vein, try figuring out whether Stephen Byerley is man or machine in Isaac Asimov's best robot puzzle-story, "Evidence."

Sf takes liberties with physics in exploring human metaphysics, kindles imaginations, tests credibility and our predictive capacities, and makes us more human by contemplating robots. Such works belong on everyone's reading list. Here's ours-

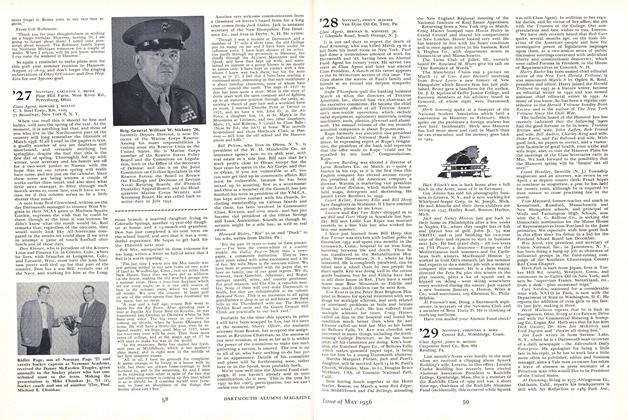

Steve Calvert

Science fiction's Siskel and Ebert: Perrin, left, and Calvert.

What if an alumnus working first in the Alumni Office and then with Continuing Education secretly intercepted the brain waves of his former faculty mentor whenever that professor opened a volume of science fiction? How would the proflet's make him an English professor gentleman-farmer/essayist/bookhound rescue his brain waves? What if the prof, suspecting his insatiable former student of perpetrating the brain drain, invited him to co-teach a course on science fiction, thereby tricking him into yielding an equal flow of brain waves in the opposite direction? It just might work. In fact, it did work. Recently English Professor Noel Perrin and Steve Calvert '68, now director of the College's Office of Continuing Education and Conferences, joined forces to co-teach science fiction. Calvert's chance to return to Perrin's classroom seems especially appropriate, for in a sense he never left it or at least Perrin's lessons never left him. "Perrin awakened my senior year with his winter 1968 course, 'The Twentieth-Century Metaphysical Novel,'" recalls Calvert. "He included J.D. Salinger's Franny and Zooey and Rabbit, Run by the then little-known John Updike. Like/4 Canticle for Leibowitz, those books asked impossible questions about what it is to be human. They were perfect for the adolescent mind, we all thought in those days. It turns out that the books ring truer the older one gets. Thus Canticle has become, for Perrin and me as adults, better and better, very much worth rereading and teaching." Calvert compares Perrin's teaching with the methods of another Dartmouth English professor, the late James Epperson. "Epperson used to say that he taught by the 'depth charge principle,' by which he dropped unfathomable ideas into students' minds that would 'go off' later to the students' delight. "Perrin's depth charges kept going off in my head until I found myself teaching science fiction with, him to more than 100 Dartmouth undergraduates. With any luck, one of them will teach a similar course with me on some of these books around, say, 2025, about the time some of these stories take place." Calvert grins, "Now that would be continuing education!" Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBlack Dan's Reunion

June 1989 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement '89

June 1989 -

Feature

FeatureWebster's Greatest Monument

June 1989 By Ed -

Feature

FeatureHow I Invented Dog Running

June 1989 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHIS HAT

June 1989

Article

-

Article

ArticlePLAYERS VISIT WORCESTER AND NORTHAMPTON

June, 1922 -

Article

ArticleThe Educational Investigation

December 1924 -

Article

ArticleBrig.

May 1956 -

Article

ArticleSaving the Whales

Mar/Apr 2007 By Bonnie Barber -

Article

ArticleTuck School

April 1947 By G. W. WOODWORTH, H. L. Duncombe JR. -

Article

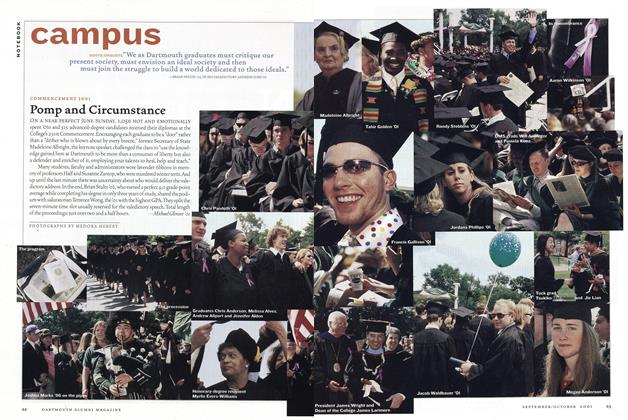

ArticlePomp and Circumstance

Sept/Oct 2001 By Michael Glenzer '01