How can you bean explorer wheneverything hasbeen discovered?

DARTMOUTH'S first alumnus to cross the Sahara was John Ledyard, class of 1776. Or, rather, he was the first to plan to cross the Sahara (he was going to do it diagonally on camelback) but he died in Cairo at the outset of the trip. He was just the first in a long line of adventuresome spirits to come out of the College, a place that has not only attracted but nurtured a remarkably high number of explorers—explorers of foreign places, explorers of human limits, explorers of boundaries of every kind.

But the exploring game has changed since Ledyard's day. Adventure pros these days have to be as comfortable in the rarified air of corporate boardrooms as in a tent at 20,000 feet. And what they set out to discover has to do with something less tangible than geography.

Dan Dimancescu '64

"Ned Gillette was always interestedin high-risk, life-threateningadventure. I was always interestedin being exposed to the back door ofcultures. It's a different motivefor adventure."

THE FIRST ONE CAME WHILE HE was still an undergraduate: 90 days and 1,600 miles down the Danube River in 1964, a crack through the Iron Curtain that hadn't been opened to foreigners since World War 11. The trip covered eight countries and generated its share of publicity—but Dan Dimancescu and eight members of the Ledyard Canoe Club who went with him did so out of goodwill, for the simple purpose of exchanging knowledge and experiences with people of a foreign culture. "We weren't out to conquer physical frontiers," Dan explains.

Threads of that first funded adventure would be woven into each of the subsequent trips: an EastWest exchange canoe trip on the Hudson River in 1965; 1,100 miles by kayak through the Inland Sea of Japan a year later; a 900-mile walk across Rumania in 1968; two and a half months of sea kayaking along South Korea's island-filled coasdine in 1987. Money for the adventures has come from a variety of sources, including National Geographic, private contributions, foundations, even a Korean television station. In all cases, the emphasis has been on international understanding. And in all cases except one, the Americans have been from Dartmouth. "I'm always looking for the best," Dan says. "People who can write well, who know music, talented people in photography and film in search of world-class experiences—each person bringing a different skill to the table. That way, we'll be as interesting to the people we visit as they are to us."

Lowell Thomas Jr. '46

"I'd always wanted to fly in aprofessional way, not just as anotherguy out of Anchorage flying aroundon weekends."

EVEN FORGETTING ABOUT THE exotic films, the brunches with kings, the times stranded on ice floes near the North Pole, Lowell Thomasjr.—author, photographer, explorer, politician, adventurerhas never been just another guy. He helped organize a special aerial squadron while still at Dartmouth, was an Air Force pilot and instructor who taught night flying to de Gaulle's Free French pilots, made a record-breaking circuit of the globe by air over both poles, and in 1983—at the age of 60—became one of the few Alaskan bush pilots licensed to fly onto the remote high reaches of Mount McKinley. "The skier in me and the climber in me all came together in my love of mountain flying," he told reporters soon after he purchased Talkeetna Air Taxi. "The timing is correct."

He has recently sold the air taxi company, spending most of his summers now flying guests for two wilderness lodges in the center of Denali National Park. On occasion he will take them up to the higher elevations where few others dare to fly, and he remains the only pilot in Alaska who can be called on to make fixed-wing aircraft rescues up into the 14,000-foot range. This past winter, the former state senator and lieutenant governor, 66 years and "going strong," has been busy planning a singleengine plane trip to the Soviet Union with his son David '79. If all goes well, yet another story and more photographs will be published by a pilot who has carried adventurism to almost uncharted heights.

Andrew Harvard '71

"He was born in New Orleans belowsea level. Its not an inherited trait.

MR. HARVARD IS JUST NOWHEADING out of the country," said the voice on the other end of the line. "But I will fax your message to him at his hotel and hope it reaches him before he leaves." Not surprisingly, it did not.

People like Andy Harvard tend to be moving targets. "He's a wonderful traveling companion—a delightful person to be with in odd situations," says Todd Thompson '70, who has accompanied Andy from the Canadian Rockies to Dhaulagiri in the Himalayas to South America's Urubamba and Ucayali rivers. In all, Andy has been part of 12 expeditions, all invoving new routes or unexplored territory.

"Andy was special," recalls English Professor Chauncey Loomis, an explorer himself. It was through Professor Loomis, who was something of a mentor, that Andy learned of the unexplored rivers of South America.

Former logger, oilfield roughneck, mountain and river guide, Everest veteran, author of one book and several articles, producer of four films with another in the works, director of the American Alpine Club, and television-commercial star (plugging Bayer aspirin), Andrew Harvard is, in his spare time, vice president and general counsel of a multinational agribusiness company headquartered in the Midwest. "I never really worried about him," recalls his mother from her home in Pine Mountain, Georgia. "In the sixties, any parent with any wits preferred a son who was into mountain climbing to one one who might be going off in all those other directions."

The most graphic depiction of the two sides of Ned Gillette—the promoter and the out doorsman. Furthermore, it's illustrative of why he's been such a success in his chosen field. "Ned's the very best of these pros from a corporate-promotion standpoint," says Jeff Blumenfeld, head of a New York public-relations firm that handles several outdoor-equipment accounts. "A lot of the others just want to have their fan and don't really care about the people whose money is allowing them to do so. Not Ned. He remembers who sent him, and he pays them back. He's articulate, very funny, charming, a good lecturer. And when he's talking, he never forgets the sponsor's name." Another defender is Mary Scott of North Face Equipment, which was one of the companies that had products to push at the Vegas gig. "Ned's been on retainer with us for 15 years now," she says. "He writes for our catalog, even. He loves doing it, and we love having him. He's our star, really."

CROSSED DRAKE PASSAGE IN A ROWBOAT. IN 1988 Gillette and three crewmates rowed a 28-foot, 1,550-pound aluminum dinghy 720 miles from Chile to Antarctica. The Passage, which connects the Atlantic and Pacific at the tip of South America, has "the worst sea-level weather on earth," according to Bob Rice of Weather Services Inc., a Massachusetts firm that predicts the weather for USA Today, among other clients. Rice, who often works with adventurers, gauged the gusts for Gillette and told him when to put the boat in the water. "I had to send them off in a Force 9 gale because there was a real chance that they'd get pasted right back into Chile during launch." The hightech boat, named the Sea Tomato for its round shape and red color, wasn't pureed upon takeoff, but was badly bruised. "We were shot out of there like a rocket," says Gillette. "We hit 30-foot seas right away. The boat capsized three times, and we all went into the drink at one time or another. We couldn't eat much and we could sleep less. Truth be told, it was awful." Thirteen seasicking days later, the Tomato bumped ashore at Nelson Island, a landfall of the Antarctic peninsula.

The next morning the Tomato's voyage was recounted on page one of The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and a host of other papers. Ned Gillette was famous.

DURING HIS 16 ADVENTURESOME YEARS, Gillette was becoming better and better at his profession. Working from a base in a one-room flat at Yosemite, and later from his home in Stowe, he was becoming increasingly adept at marketing his life, and thereby perpetuating his chosen lifestyle. He was studying photography; eventually his words and pictures appeared not only in books but in National Geographic magazine. He was developing a winning stage manner, and becoming a fixture on the adventure-lecture circuit. Once the Sea Tomato voyage had succeeded, Gillette found himself second only to Steger as a draw. He was able to ask up to $800 for a slide presentation

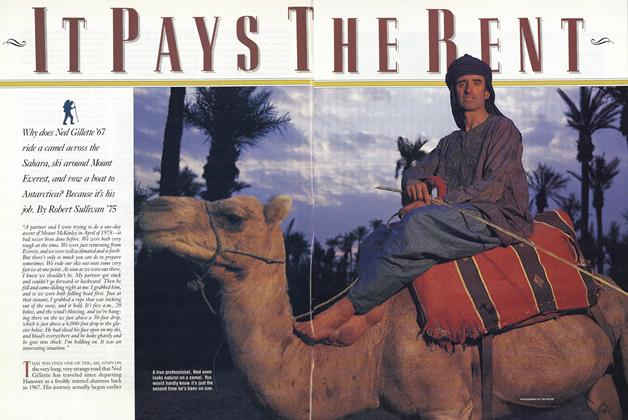

It was after one of his Sea Tomato lectures that Gillette was introduced to Michael Kirtley and to his idea about a camel ride across Africa. "It sounded like a neat idea," Gillette says simply.

Well, sure it did. So Gillette put on his public-relations shoes and fandangoed down to Morocco. His intent was two-fold, as it always is at that stage of a venture (adventure). He needed to sell his hosts on the attractiveness and thus the benefit of hosting, so that all the necessary clearances, visas, and so forth would be effortlessly acquired in the months ahead. And he needed to start developing a concrete game plan to pitch to the corporate sponsors who had the moolah necessary to mount the extravaganza itself. Don't begrudge Gillette, vis-a-vis money. Cash-for-play is a time-honored tradition. Admiral Robert Peary raised a huge stake up front, much of it from the National Geographic Society, to press his attack on the North Pole early in the century Last year Steger raised some $6 million before he set off across Antarctica. Next to that, Gillette's projected $2 million tab for a half-year of caravaning seems cheap. Gillette says the money will cover all transportation, food, rescue support services, and incidentals.

To accumulate the loot, he is in Morocco, working with a video crew. The resultant film will be shown to fat cats, and if all goes well—if the sun is setting just so behind a dune, and if Gillette looks properly majestic atop a camel—then the money should start to flow.

The Marrakech Express has arrived now in Marrakech, and Gillette and company proceed to board horse-drawn carriages for the dusty trek to the Adas Asini Hotel. There they are greeted by native Moroccans, traditionally garbed, who are banging drums and chanting loudly in honor of the daring Westerners who will ride the camels. The funny thing is, as Gillette admits in the hotel lobby, "I've never been on a camel. Not yet."

Before Gillette gets to experience his maiden mount, there is other work to be done. There is a grandiose dinner to attend at The Oasis, a theme park on the outskirts of Marrakech. The Oasis offers rides a la Disneyworld and "authentic" dining a la Epcot. This story is passed around during dinner: the Moroccan who built The Oasis—a man whose wealth would allow him to scoff at Forbes's mere mews in Tangiers—was positively mesmerized during a visit to the Disney layout in Orlando a few years back. He flew home thinking, "I want something like that!" And now he has it. After enjoying a half-dozen examples of what you can do with lamb and rice, the entourage is entertained by a sumptuous stage production mounted on the other side of a cement pond. It is colorful, it is loud, it is Moroccan.

As a historical footnote, it should be recorded that this is the evening of Ned Gillette's first camel ride. One Oasis attraction is camel rides. Amid some man-made sand dunes, real camels lie desultorily. They are chewing their cud (if that's what camels chew) and awaiting adults or kiddies who are courageous enough to climb aboard. The intrepid Gillette is. So is Susie Patterson. At the behest of the nomads/guides/camel-rideoperators—whatever they are—the camels arise, bearing Westerners. They stroll casually around the dunes. With attendants leading the beasts by ropes, this looks like an African version of that pony ride we each took as a kid—the one where the teenage girl led the little horse 'round and 'round a circle.

Gillette appears childlike, a little Neddie of Arabia. To his credit, he is ablush.

Back at the hotel, there is still more work to be done. At 1:30 a.m. local time, he is to appear on a radio talk show that is being beamed to listeners throughout Kentucky, home base for Kirtley's America to Africa Society. Kirtley is friends with the talk-show host, Milton Metz, and so Metz and a production colleague are here, in a makeshift studio in the basement of the Atlas Asini, ready to inform listeners from Louisville to the Blue Hills about the great prospective camel caravan.

1:31 precisely: "Hello America! This is Metzo coming to you live from Marrakech, Morocco!" Gillette briefly explains the venture, and then Metz opens the phone lines. The first four questions are about the weather. How is it? Metz and Gillette agree that it's wonderful—sunny, dry, in the 80s. The fifth question is directed at another of Metz's guests, Morocco's Secretary of State, believe it or not, who has graciously traveled from Rabat to appear on this transoceanic radio show.

What, the caller asks, is the favorite dish of the Secretary of State, and how does one prepare it? The Secretary of State is nonplussed for barely a moment, then happily gives the recipe.

Talk show ended, Gillette shakes his head wearily and confides, "Sometimes, it is a truly strange business I'm in."

Next morning, things get stranger still. It's decided that there's not enough time to reach the real Sahara, some 300 miles south of here, in order to shoot some video of Gillette on a camel. So the crew returns to the Oasis, borrows a couple of camels from the camel-ride attraction, and repairs to a scrubby field outside the theme park. "This looks pretty much like a desert," the cam eraman says.

Also on hand is Mano Dayak, the Niger nomad who is to co-direct the caravan with Gillette. "The lord of the desert," as he is known to readers of European adventure magazines, helps Gillette and Patterson into their brightly colored saris and turbans. He gives them a brief lesson on camel riding. "You'll be better at it by next year," he reassures Gillette. "These tourist camels are stupid anyway. We'll have real camels for the caravan."

The cameraman shoots for four hours, and finally loses his desert sun. Gillette, stiff and sore, dismounts. "I kinda wish we'd been in the real desert," he says. "It's pretty weird, coming all this way and then shooting in a place that's posing as the desert. Sometimes I wonder at all the weird stuff that goes into putting an expedition together.

"Still, it's all worth it once you're out there. The adventure's the thing. It's thrilling, and it's real."

That's it, of course. It must be re-emphasized: the snake-oil side of Ned Gillette's career is more than counter-balanced by the risk, danger, and golden adventure on the other side of the scale.

Consider: the next time We caught up with Gillette after the Moroccan circus was in New York City. He was on another lecture tour, and this one had taken him to the terra incognita of deepest Manhattan (shiver).

What, we asked, had Ned been up to lately?

"Well," he said unassumingly, that small and constant grin appearing. "This one was interesting. It was exactly unlike all that Moroccan madness. Susie and I did something a lot quieter. I call it 'guerilla skiing.' There's a peak in Tibet, the summit's well over 20,000, and I'd guess it's never been skied. We came up with a plan. We'd go to Nepal, and work our way slowly up to a high camp. We'd use guides for that. Then, at night, we'd cross the border and shoot for the summit. You see, it's in the part of Tibet that's off limits. It's really at the roof of the world. No one's supposed to be there.

"Anyway, we got across the border and we found ourselves in this high, beautiful valley. We camped there several nights, skiing and climbing and exploring. The thing is, we never did make the summit—it turned out it was impossible. But that valley—where no one's ever been, perhaps—was Heaven. It was Lost Horizon, it was something else."

There are two sides to Ned Gillette, the "out there" and the "back here." High in a snow-filled valley in Tibet, that's as out there as you can get. That's Ned, pure.

AN ALUMNI MAGAZINE DOES NOT SEND WRITERS TO MOROCCO very often, but for Bob Sullivan '75 we gladly made an excepft. tion. For one thing, the King of Morocco paid for it. Last fall, Bob called from his home in New York City to tell us about Ned Gillette's next big expedition. As part of the pre-adventure publicity effort, the king was flying some American writers to Africa. Since Bob's employer, Sports Illustrated, wasn't sure it wanted a story, Bob asked if we were interested.

Bush pilots' bush pilot.

Dimancescu catches rays andgoodwill by kayaking.

Harvard theexplorer.

Ned won the nordic timetrials at Holdernesswhen the guy in front ofhim fell down.

"Now, in theworld ofadventuing,Ned Gillette isbig and themountains havegotten much,much bigger."

"The snake-oilside of Gillette'scareer is morethan counterbalanced by therisk, danger, andgolden adventureat the other endof the scale."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

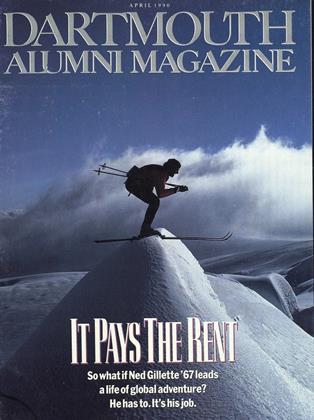

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

April 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

April 1990 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOn chemistry, Cuba, and other radical elments on the campus.

April 1990 -

Article

ArticleThe Satanic Verses: Why Were Muslims So Offended?

April 1990 By A. Kevin Reinhart -

Article

ArticleA SENSE OF PLACE

April 1990 By Professor Jere Daniell '55, Joni B. Cole -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

April 1990 By Kenneth M. Johnson

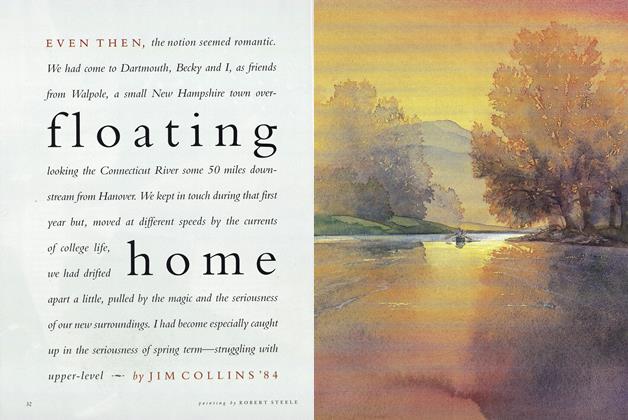

Jim Collins '84

-

Feature

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleBaseball and the Pursuit of Innocence

June 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureCOACHES

SEPTEMBER 1996 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryANDREW WEIBRECHT '09

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

FEATURE

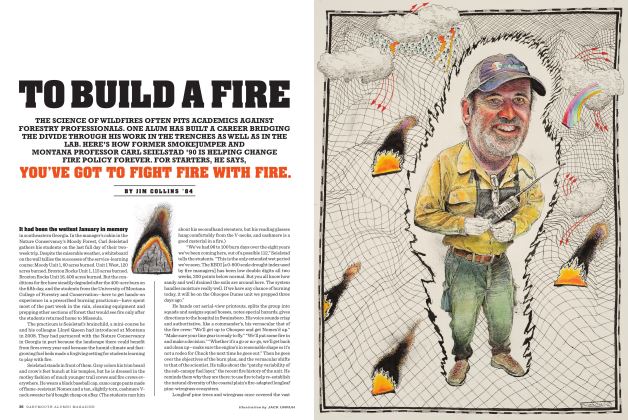

FEATURETo Build a Fire

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Sports

SportsMoneyball

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By JIM COLLINS '84